Writing History, Uncovering Truths

This year—2021—marks the hundredth anniversary of the 1921 race massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Will it take another hundred years before our nation has full and complete clarity about what happened?

Recent social justice protests have sparked a new awakening to right historical and contemporary wrongs. George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, was a watershed moment for recognizing systemic racism and how, since the dawn of slavery, brutality continues to oppress Black lives.

Video of Floyd’s killing, widely shared around the world, served as a catalyst for others to “bear witness” to racial horror. Technology spoke. The murderous tale couldn’t be buried, unwatched, or untold. Black Lives Matter protesters connected links between past and present trauma, and, for the first time, the Tulsa Race Massacre was widely discussed in the media and protest communities.

The Tulsa Race Massacre, like so many atrocities against African Americans, had been hidden and voices silenced for so long that it almost disappeared from national consciousness.

In a 1983 Parade magazine, I read the headline: “The Only US City Bombed from the Air.” A black-and-white photo, taken in 1921, showed a community burned to ash. The story, no more than a few paragraphs, cited the basic “facts”: Dick Rowland, a shoeshine, was accused of assaulting a white female elevator operator. A white assault ensued and the National Guard bombed Deep Greenwood, a thriving Black community known as Negro Wall Street. More than four thousand Blacks were interned in tents for nearly a year and forced to carry green cards.

The subject haunted me emotionally and intellectually. How was it that I’d never heard of the Tulsa Massacre? When did Blacks migrate to Oklahoma? Why was this history suppressed? During my research, I found that Dick Rowland and Sarah Page, the white woman, were victimized by yellow journalism that inflamed racial tensions. Ultimately, charges against Rowland were dropped—Page refused to testify.

As a writer, I’ve always been committed to uncovering suppressed stories. Historically, the event wasn’t taught in school curricula, and some children raised in Deep Greenwood first learned of the tragedy once they left Oklahoma.

Thirty-eight years ago, I clipped that Parade magazine article, knowing eventually I would write a novel. Why a novel? I’ve always believed that fictional characters invoke empathy, so readers not only recognize but feel the horrific tragedy of humanity under attack.

Researching the massacre in the 1980s, I was told the massacre “never happened,” threatened, and called a liar. Scott Ellsworth’s Death in a Promised Land (1982) was an important inspiration. His book, for me, was an emotional and literary “tuning fork,” affirming the massacre happened. Meeting Mr. Ellsworth in Tulsa, I can still hear his words: “They’re searching for the mass grave.”

Nine years later, with my first novel, Voodoo Dreams, published and newly employed as a professor at Arizona State University, I turned to writing Magic City.

True to the African American oral tradition, in order to begin a tale, I need to hear the character’s voice. It took six months for Joe, the protagonist’s voice, to spring from my soul:

Joe Samuels had decided to quit dreaming. Decided to stop dreaming of leaving Tulsa, of discovering new horizons streaked with magic. Yet here he was lying by the tracks, his head to the ground, listening to the rumblings of the 9:45 preparing to leave, trailing Pullman cars and flatcars loaded with cotton and crude.

Weary, disoriented, Joe needed to sleep. He wanted to ride the rails over the Rockies to the Pacific in a sleeper car, cozy, dreamless in an upper bunk. He didn’t want to dream of dying. Three nights in a row, he’s had the same dream. A dream that he senses was more than a dream—a haunting, a premonition, an evil worked by the Devil.

Magic City is an imaginative rendering of the Tulsa massacre. Dick Rowland bears no relation to my character, Joe, just as Sarah Page bears no resemblance to my Mary. As a novelist, I invented characters struggling to define themselves and their responsibilities to their communities. I envisioned a spiritual awakening that sustained the human spirit in a time of crisis. Mary and Joe’s humanity is as important in my novel as the massacre.

In Magic City, I envisioned a spiritual awakening that sustained the human spirit in a time of crisis.

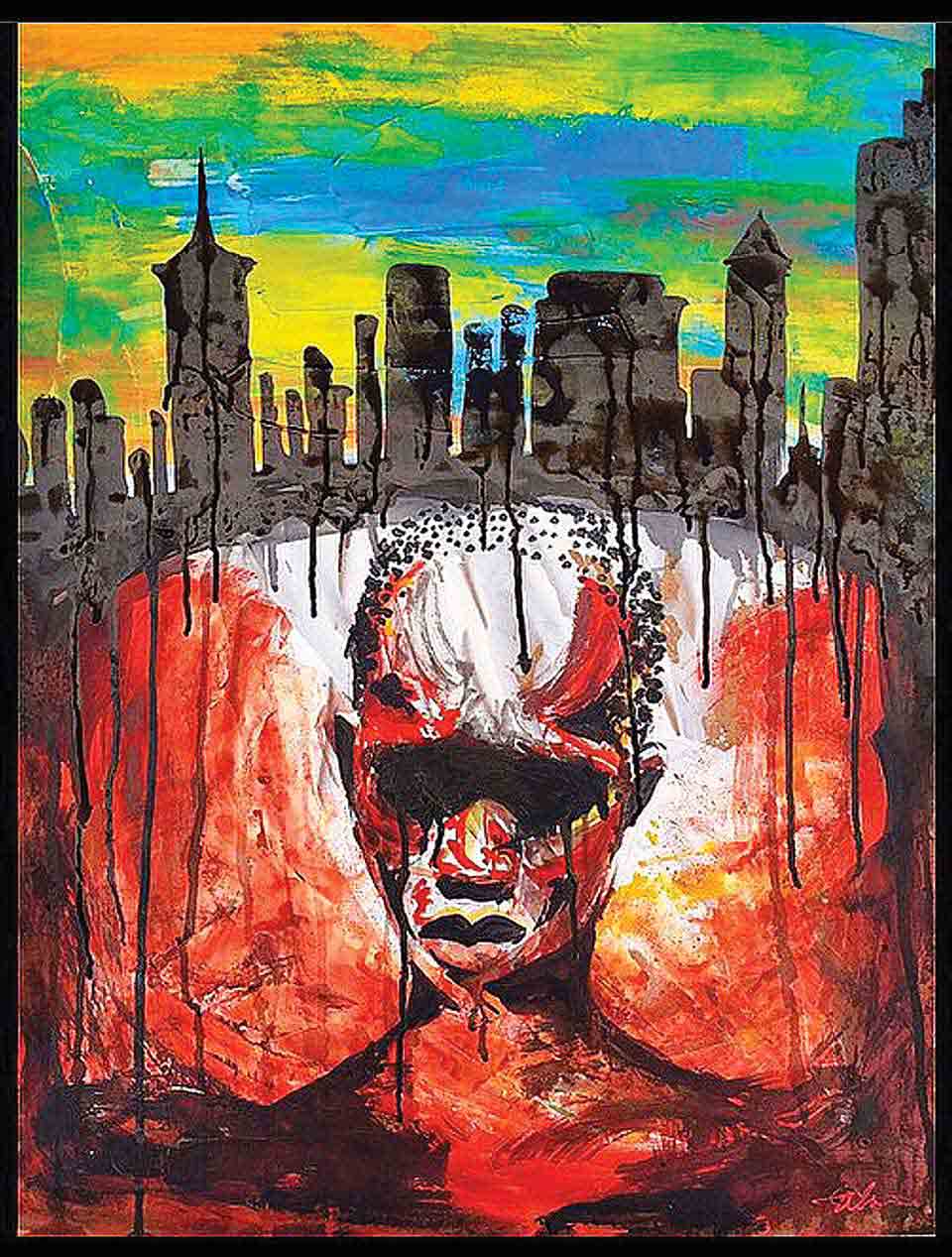

Joe is having vivid dreams of being lynched and set afire. The novel’s opening is Joe’s attempt to bargain with fate: promising not to migrate further west (a lesser-known African American migration pattern) and not to rail against the racist confines of Tulsa. By the end of the novel, Joe recommits to Deep Greenwood, his home, and the fight for social justice.

Joe is having vivid dreams of being lynched and set afire. The novel’s opening is Joe’s attempt to bargain with fate: promising not to migrate further west (a lesser-known African American migration pattern) and not to rail against the racist confines of Tulsa. By the end of the novel, Joe recommits to Deep Greenwood, his home, and the fight for social justice.

When I discovered Tulsa was called the “Magic City” during the 1920s, I thought of America’s spiritualism movement, Houdini, and the linking of African American and Jewish traditions in the spiritual “Go Down, Moses.” Tulsa, during the 1920s, was a stronghold of KKK activism, which included the persecution and lynching of Jews, suspected communists, and prolabor leaders. The character David Reubens was created as another bridge between Jewish and African American struggles to escape bondage, and as an illustration that prejudice blunts growth, literally and spiritually. My novel’s ending affirms love and the greatest civil right: the ability to determine one’s identity despite and in spite of discrimination.

Publishing has always lacked diversity. I was thrilled Magic City was under contract. Spreading the history of the 1921 massacre seemed a certainty.

Inexplicably to me, my editor refused to publish the manuscript, saying the characters were “unlikable” and it wasn’t clear that the white woman “didn’t ask for it.” I was floored. Magic City was inspired by America’s classic racist trope that a white woman was sexually assaulted by an innocent Black man. This rumored assault sparked the massacre. While I was ready to do any revisions to improve my novel, my contract was abruptly canceled.

HarperCollins then acquired the book and launched it with an impressive ten-city book tour in 1997. Finally, seventy-six years after the Tulsa massacre, the first novel about the massacre would be widely available. Except it wasn’t. Starting my tour in Atlanta, bookstore after bookstore didn’t have copies of my book. I was told it was remaindered. Rumor said the fault was corporate reorganization.

Finally, seventy-six years after the Tulsa massacre, the first novel about the massacre would be widely available. Except it wasn’t.

A year later, HarperCollins sent me on a paperback tour. I arrived in Oklahoma City right after the veteran, Timothy McVeigh, had been convicted for domestic terrorism for the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. One hundred and sixty-eight people died, and over 608 were injured. Of course, my planned Borders bookstore visits in Oklahoma City and Tulsa were both canceled. Yet the irony of quick justice for a primarily white assault in a federal building and the lack of justice for a seventy-seven-year-old Black community massacre didn’t escape me. Echoes of inequitable policing and justice still haunt America. Excessive police and military force for Black Lives Matter protests contrast with the relative ease of access of domestic terrorists on January 6, 2021, who stormed the nation’s capitol. The vigorous pursuit of these terrorists also contrasts outrageously with the lack of prosecution of white supremacists and police officers who still to this day kill people simply for driving, talking, walking, and being Black.

After Magic City was published, the Tulsa World sent a reporter to interview me who had also done a book review. He suggested Magic City should be nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. (A copy of his interview and review remain in my files.) Tulsa World, the city’s premier newspaper, never published the interview or the book review. A year later, at Tulsa LitFest, I encountered the newspaper’s editor. “It’s nothing personal,” she remarked. How could it not be personal as well as antagonistic to Black cultural and historical truths? Presumably, subsequent generations of white Tulsans feared reprisal so much, they couldn’t even bear to publish an interview or review of a fictional account of the real massacre. Several national reviewers, I later learned, received hate mail for discussing a novelization of a “fabricated” event.

To me, it makes a perfect, traumatizing sense that the first time I saw the robed Ku Klux Klan was in Tulsa. It was another Tulsa LitFest event, and my biracial middle-grade daughter accompanied me. Both of us were deeply shocked to be within a few feet of grown men dressed as pointy-headed ghosts. Covering my pain, I tried to joke, “Wow, going on a field trip with Mom, you get to see the Klan!” My daughter and I further deepened our conversation about race. Knowing how the KKK terrorized Blacks, we discussed how the police officers—Black and white, male and female—were protecting the Klan’s (for the moment) peaceful, sign-carrying protest before the courthouse steps.

Flash-forward, it is now nearly a hundred years since the Tulsa massacre. President Trump in 2020 convened his first, maskless, not socially distant rally in Tulsa during the Covid-19 pandemic. Though it has been denied, there’s no doubt in my mind that the Tulsa rally was a dog whistle for white supremacists. Sadly, three weeks after Trump’s rally, virus cases soared. Herman Cain, a rally attendee, former Republican presidential candidate, and a Black man, died from Covid-19.

In recognition of the hundredth anniversary of the Tulsa massacre, twenty-four years after its first publication, Magic City is being reissued.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, publishers are making a concerted effort to publish more diverse voices and to promote social justice. The aim is to change the master narrative—to allow no story ever to go untold.

I still believe history has power to teach and unite us. I believe artistic representations (whether visual, musical, fictional, etc.) can promote much-needed empathy and healing.

I still believe history has power to teach and unite us. I believe artistic representations can promote much-needed empathy and healing.

Unfortunately, white supremacists today continue to promote racial and religious discrimination. Yet chants of “Jews will not replace us” and Black Lives Matter deniers have been met with multiethnic and multigenerational protests. Prejudice and implicit bias are not dead, but I’m inspired by the coalition of people who are beginning a new civil rights wave.

In October 2020, archaeologists excavated part of Oaklawn Cemetery in hopes of finding the more than three hundred people killed during the Tulsa Massacre. Twelve bodies have been unearthed but not yet identified.

There are still thousands of smaller stories within the larger 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre that have been suppressed and lost. Will it take another hundred years before our nation has full and complete clarity about what happened, how many died, and who were all the destroyers and murderers?

My hope is that my novel, Magic City, continues to inspire and to affirm that hatred for any reason—race, religion, gender, class—diminishes us all.

All stories deserve to be told. Especially those that have been buried, purposefully not told.

Arizona State University

Author’s note: With profound gratitude to Jane Dystel and Miriam Goderich of Dystel, Goderich, and Bourret. Thank you for believing. Heartfelt thanks to Peternelle van Arsdale, my brilliant editor. In loving memory of Jan Cohn, whose wisdom and guidance inspired me. Extra special love to Brad, my husband and first reader—vous et nul autre.