Cuba at the Table: Waiting for Change Again

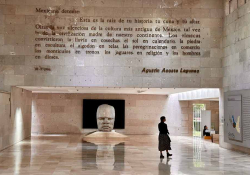

YOU HAVE TO WALK TOWARD THE Callejón del Chorro, alongside the Cathedral of San Cristóbal in Old Havana, to get to Doña Eutimia. The private restaurant or paladar—one of the most well known in the capital, and one of the few that has managed to make its way onto the most in-demand tourist sites—awaits its guests next door to the Taller Experimental de Gráfica. It’s small, and yet the clientele is aware of the privilege it confers. It’s recommended, of course, to book in advance, because there’s always someone waiting to take the first available chair, if there is one, at one of its few tables. Doña Eutimia represents more than twenty-three years of work, prestige, and, of course, authentic comida criolla (Cuban cuisine). The secret of their success: black beans, ropa vieja (shredded beef in tomato sauce), the favorite of my friend and translator George Henson, as well as other traditional dishes. Decorated with screens, lamps, and works by national artists, this cozy restaurant is more than what’s on the menu; it’s the experience that has managed to preserve its charm.

Named for a señora who once cooked for the painters and artists who worked in the adjacent engraving workshop, the real-life Eutimia won the affection and praise of creators of all types, and today her memory lives on in the restaurant that bears her name. On one occasion, I took a rather haughty and formal academic friend to a lunch, together with a group of American professors, and it amused me to see that such a professorial man waited as the others served themselves the thick black beans, only to repeat the Cuban custom, so typical of humble families, of cleaning the serving bowl with scraps of bread, to enjoy the delicacy to the fullest. Good food has that power: it frees us from certain atavisms and airs to return us to the mere pleasure of unabashed pleasure.

To keep a paladar open—especially one celebrated for its famous menu and with ingredients in high demand—is a true feat in today’s Cuba. The unavailability of supplies, the internal failures of the national economy and its mechanisms, the weight of the US embargo imposed on the island, and the reduction of points of entry for seasonings and other products—for reasons that Covid-19 has only aggravated—have compounded and belie the boom image that trade, small businesses, and cuentapropistas (entrepreneurs) enjoyed not long ago. During the brief bridge of exchange that the Obama administration built between 2014 and 2016, hopes multiplied. Then, everything changed dramatically. And the negative impact has even reached the table of such famous restaurants (and away from the pockets of “ordinary” Cubans) as La Guarida, where essential ingredients for their select and exclusive menu have vanished.

Beginning January 1, the Cuban government launched the Tarea Ordenamiento (restructuring of the country’s economy), which includes the withdrawal of the CUC—the convertible peso that tourists exchanged for dollars—and a revaluation of the Cuban peso. It’s a delicate context, amid numerous shortages, of a dissatisfaction that manifests in long lines, a meteoric rise in prices, the end of subsidies, and the changes that Cubans are demanding on social media from the government beyond mere sloganeering, despite the consequences that such actions exact.

In 2021 the island’s resistance and hope will be put to the test once again. Hopefully, in a not-so-distant future, we’ll be able to talk about all of this, sitting at a table at Doña Eutimia, waiting for the black beans to arrive. Because one doesn’t live by faith alone.

Translated from the Spanish