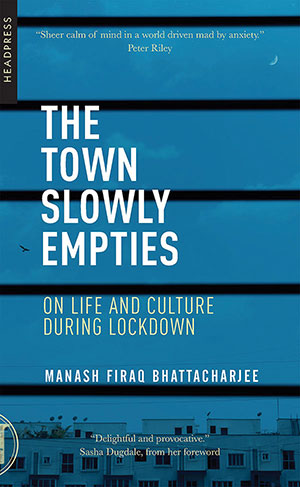

The Town Slowly Empties: On Life and Culture during Lockdown by Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

IN HER FOREWORD to The Town Slowly Empties (Headpress, 2021), Sasha Dugdale describes this slim hybrid as the author’s “lyrical diary of lockdown in India.” The diary begins on March 23, 2020, the first day of Covid-19 lockdown in India, and ends on April 14, when the author wakes to the news that the lockdown has been extended to May 3.

Like Dugdale, I appreciated the journal style, which “allows a degree of freedom to move about and tackle what concerns the writer on any given day,” as well as the international reach of Bhattacharjee’s cultural touchstones and how he focuses his eye on the pandemic’s effect on the poor. In his first entry, when “the pandemic is banging on India’s door,” he reflects on the migrant laborers, “whose daily earnings have suddenly disappeared as they face a situation of imminent hunger,” leading to a mass reverse migration. Bhattacharjee returns to them throughout the book.

Unable to move freely in the outside world, the writer’s mind moves freely across politics, philosophy, literature, and film, often with a startling range of reference. His April 1 chapter opens quietly, the writer sitting on his porch observing two parrots. He soon moves to T. S. Eliot, Chaucer, Dickinson, the 1962 film Kanchenjunga, and Darwish. We then accompany the writer to the kitchen, where he cooks pabda, “a fish of delicate taste.” He shares his tips for cooking pabda (garlic first, ginger later) and then moves into his inspiration for cooking. Soon we arrive at Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate, the actress Jean Seberg, and Carlos Fuentes’s Diana. The next chapter focuses on Satyajit Ray’s films; in the next we find Romanian philosopher E. M. Cioran; and in the next Werner Herzog, Svetlana Alexievich, and Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 sci-fi film, Stalker.

Somehow at home among the many literary and culture references—and discussions of nationalism, Montaigne, and “the gospel of reason”—we find the quotidian. There, in these personal close-ups, we likely recognize ourselves. Like Bhattarcharjee, we’re cooking to keep our hands busy, cutting our own hair, and standing in our closets staring at the clothes we once wore as if they are from a former life. For separated lovers, the lockdown drops “between them like a gate at a railway crossing. The train of days rolls by endlessly.”