Why Does Workers’ Literature Matter?

A group of Chinese migrant workers, who call themselves New Workers, have been uttering their voices through the medium of literature. The emergence of New Workers’ Literature in contemporary China is significant, because it challenges the middle-class definition of literature and structure of feeling in today’s capitalist empire.

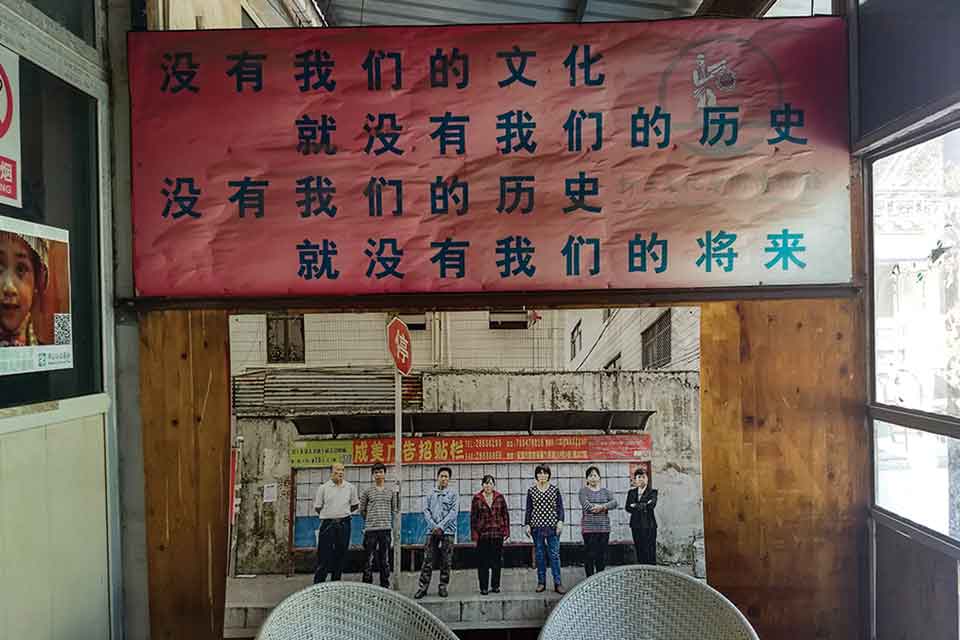

“Without our culture, we have no history, without our history, we have no future.” This mission statement can be read in a banner over the entrance of the Migrant Workers’ Museum in Beijing’s suburb of Picun. Some of the migrant workers have been meeting for two hours every Sunday evening in Picun since 2014, with Beijing-based academics and writers mentoring them. During those meetings, members read canonical works of world literature by Franz Kafka, Daniel Defoe, Lu Xun, Yukio Mishima, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, and others, but what excites them most is reading and commenting on their own prose and poetry. They call themselves “New Workers.”

In China, there are nearly three hundred million migrant workers. Working in low-paying factories and at construction sites, they have built Chinese cities but cannot become urban residents themselves owing to China’s strict household registration (hukou) system. They are wage-earning “workers” but are still documented as “peasants” with little access to education, housing, health insurance, pensions, and vehicle licenses. Precarious both in terms of livelihood and identity, Chinese migrant workers are a constant reminder of the awkward position of postsocialist China, a socialist political system with a capitalist economy.

Chinese migrant workers are a constant reminder of the awkward position of postsocialist China.

Their writings are diverse, ranging from pungent social commentaries to sentimental self-reflection, and from historical testimony to ruminations about humanity. Resisting stereotypes placed on peasants and workers along with different forms of social injustice in the age of globalization, this cohort of migrant workers is determined to show the world that they can speak for themselves, of themselves, and by themselves.

Migrant-worker writing is an important part of working-class literature and is getting recognized worldwide. The existence of this new literature is particularly significant because literature in our time is heavily imprinted with middle-class taste, structures of feeling, and world perspective. Encyclopædia Britannica defines “literature” as “imaginative works of poetry and prose distinguished by the intentions of their authors and the perceived aesthetic excellence of their execution.” This definition of “literature,” however, is a modern convention. Raymond Williams has told us that the shift of the meaning of “literature” from “learning” to “taste” or “sensibilities,” and the specialization of “literature” to “creative” and “imaginative,” emerged in the eighteenth century and was not fully developed until the nineteenth century (see Marxism and Literature). Because “taste” and “sensibility” are essentially bourgeois categories, it would be almost impossible for working-class literature to measure up to this standard entirely or become a best-seller. In our time, reading and writing literature is deeply intertwined with commercial culture and usually requires disposable time and wealth. As a result, our culture doesn’t even have the language, sentiments, and narratives for having a discussion about realities outside of the middle-class world—a lack that would ultimately impoverish literature and humanity.

The prose and poetry of Picun are characterized by the unadulterated truth that they represent.

The prose and poetry of Picun are characterized by the unadulterated truth that they represent, overwhelmingly opting for personally expressive poetry, biographies or autobiographies, and journalism over high fiction. At the same time, the New Workers’ literature brings another kind of creative source and literary practice into contemporary literature. To borrow Williams’s words again, the migrant workers’ literature can challenge and extend the existing literary tradition by “making ‘truth’ and ‘beauty,’ or ‘truth’ and ‘vitality of language’” (Marxism and Literature).

While reading and writing has become ubiquitous in the information age, literature as a social practice continues to wane. With the overstimulation of consumerism and the atrophy of social life, which depleted people’s practical sense of reality and dumbed down their moral standards, globalization has created a seemingly impregnable power structure that prevents people from interrogating values and constructing meanings. This is why workers’ literature matters: it can help us understand a different culture, obtain a new view of history, and possibly imagine an alternative future.

University of Oklahoma