The Sound of Silence: Chinese Domestic Workers’ Literary Writings

Since the economic reform launched in 1978, China has witnessed a vast group of rural women leaving their families behind in the countryside to enter urban middle-class homes as domestic workers. However, these domestic workers’ physical and emotional closeness to their employers is often seen as a problem, sometimes even a threat to the maintenance of the proper domestic order. Recently, a growing number of domestic workers have participated in the Literature Group at the Workers’ Home in Picun to break the longtime silence to tell their own stories revealing social injustices and inequalities at the intersection of gender and class.

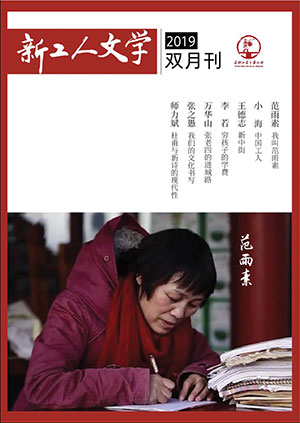

of New Workers’ Literature

On April 25, 2017, a long essay titled “I Am Fan Yusu” was first published on NoonStories, a WeChat public account featuring nonfictional writings.[i]Within twenty-four hours, this article was viewed over one hundred thousand times and reposted hundreds of thousands of times on various social media platforms like WeChat or Weibo.[ii]. In the following weeks, the “Fan Yusu” fever even spread to state and international media, including People’s Daily and China Daily, the most authoritative newspapers run by the Chinese Communist Party, as well as the Economist and the Guardian.

This article is an autobiographical account of Fan Yusu, a domestic worker who once lived in Picun on the outskirts of Beijing. Born in 1973 to a rural family in central China, Fan Yusu first worked as a primary schoolteacher in the village after graduating from middle school. At the age of twenty, she went to Beijing as a migrant worker, first as a waitress and later as a live-in nanny, or baomu in Chinese. Her life trajectory is typical of hundreds of millions of women migrant workers from rural China.

Why would an autobiographical essay make such a huge hit? What is the social and cultural significance of this domestic worker’s self-writing? To find answers to these questions, we must understand the literary tradition of representing domestic workers and the sociological significance of this group in China’s economic boom.

The domestic worker or nanny, as a representative persona of disadvantaged social groups, has been an important subject of Chinese realist literature since its birth. In the humanist-spirited works composed by left-leaning writers in the long twentieth century, the nanny is often portrayed as a stereotypical traditional Chinese woman who silently puts up with all kinds of suffering and social injustice. Lu Xun, often dubbed as the founding father of modern Chinese literature, renders such a voiceless and self-erasing figure as the “dark, kindly Mother Earth.”[iii] Women writers such as Lin Haiyin, Yang Jiang, and Wang Anyi have written about domestic workers from a gendered perspective to highlight both sexist and classist oppressions of the marginalized group. In other words, the domestic worker has been a staple figure standing at the intersection of minor literature and feminist literature who strives to reveal the everyday experiences, struggles, and concerns of disenfranchised social groups along gender, race, class, and age lines.

However, these canonical literary works about domestic workers have rarely been authored by the workers themselves. Even during the socialist period when the Chinese Communist Party promoted and organized literary activities for factory workers and farmers, few writings by domestic workers could be found, mainly for two reasons. First, many domestic helpers were illiterate elderly women who were confined within a domestic space that was not even their own home. Second, in comparison to industrial workers or farmers living and working in the same commune, they were less organized due to their migrant status from rural to urban. As a result of their more isolated working and living conditions in an informal employment sector, little institutional support was provided to encourage their literary productivity. All these socioeconomic constraints and displacements made it nearly impossible for domestic workers to pick up a pen to write their own life stories.

Four decades after the economic reform launched in 1978, China’s economic boom has also given birth to a rising urban middle class that resorts to purchasing commodified private home ownership as well as commodified domestic labor to fulfill a dream of domestic bliss. As a result, China has also witnessed a vast group of rural women leaving their families behind in the countryside to enter the urban middle-class home as domestic workers. However, these domestic workers’ physical and emotional closeness to their employers is seen as a problem, sometimes even a threat to the maintenance of the proper domestic order. A proliferation of tabloid news reports and mainstream media products constantly shed negative light on the nanny figure. For example, a recent megahit TV show, All Is Well (2019), portrays how a young domestic worker uses her sexual appeal to manipulate her aging employer and con him out of all his assets. As a result of all these sociocultural stereotypes, domestic workers are disparagingly called “little nanny,” a name suggesting their low socioeconomic status, decreasing average age on a competitive labor market, and moral ambiguity as the “intimate stranger” in the urban middle-class home.

Against such a prevailing sociocultural current of demeaning domestic workers, Fan Yusu’s autobiographical writing is groundbreaking as arguably the first piece about and by a domestic worker that has attracted so much media attention and stirred up a series of heated public debates. It chronicles her life and work, providing an alternative gendered narrative in a female migrant laborer’s own words and giving voice to those belittled and silenced domestic workers who are scattered and besieged in millions of urban middle-class families.

In this sense, Fan’s self-writing continues both traditions of minor literature and feminist literature since the turn of the twentieth century. More importantly, her participation in the Literature Group at the Workers’ Home in the Picun and frequent interaction with other migrant-worker writers suggest the formation of a small literary commune outside of the mainstream literary circle. Fan’s writing has inspired more domestic workers to write and publish their own stories.

When I visited the Literature Group in June 2019, Fu Qiuyun, a woman migrant worker who founded the Literature Group upon the suggestion of some fellow workers with a strong interest in literature, told me that the Literature Group has been the most popular and long-lasting branch unit of the Workers’ Home. Its regular participants vary from ten to twenty. People come and go because they often change jobs and living places since migrant workers are not guaranteed job security or life stability.

At the beginning there were very few women workers participating in the Literature Group. Fan Yusu was an exception. After the publication of her autobiographical piece, an increasing number of domestic workers have recently joined the group to read, write, and discuss literary works. As Picun is located far from the urban center of Beijing where most migrant workers live and work, these workers have to spend long hours taking buses or subways to get to the Literature Group. Sometimes they are so absorbed in the ongoing literary activities that they would stay too late and miss the last bus or subway back to the city. Since taking a taxicab was considered too expensive, they would spend the night in the office of the Literature Group next to the Migrant Workers’ Museum at Workers’ Home.

This belittled and demeaned social group has shown great enthusiasm creating their own writings, often in colloquial or sometimes even crude language, to deal with topics that are usually perceived to be trivial or insignificant by official literary history and mainstream media. In comparison to canonical literary works, their writings are less structured or refined, and easier to read and write for domestic workers whose packed schedules and frequent job changes only allow them to dedicate some fragmented time to literary efforts in their off hours.

With their writings, these domestic workers have broken the longtime silence to find their own voices and critical visions. The Literature Group has provided them with a cultural home in a strange city and a locus for a growing network of domestic-worker writers. Through creating their own cultural texts, the belittled domestic workers demonstrate the power of smallness—namely, to assemble the energy and agency of “small,” atomized individuals to establish a novel form of literary commons and to create a grassroots lifeworld not recognized by mainstream media and middle-class culture.

University of Kansas

[i] Fan Yusu, “I Am Fan Yusu” (Wo shi Fan Yusu), NoonStories, April 25, 2007.

[ii] WeChat, or weixin in Chinese, is one of the most popular social media platforms in China. Weibo, literally microblog, is another widely used social media app in China.

[iii] Lu Xun, “Ah Chang and the Book of Hills and Seas” (Ah Chang yu Shan hai jing), in Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk (Zhao hua xi shi), trans. Yang Hsien-yi & Gladys Yang (Foreign Languages Press, 1976), 25.

Read “I Am Fan Yusu,” a digital exclusive translation.