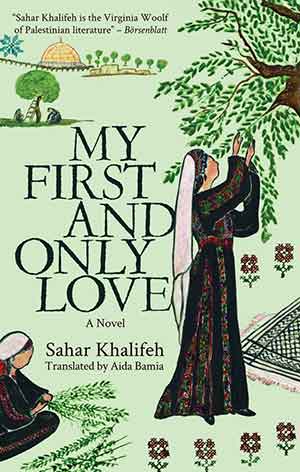

My First and Only Love by Sahar Khalifeh

Cairo. Hoopoe Press. 2021. 401 pages.

Cairo. Hoopoe Press. 2021. 401 pages.

THE ARABIC READER IS witnessing an evolution in the Arabic novel, particularly in the past decade and in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. Novelists have been experimenting with new forms, styles, and topics of interest. Sahar Khalifeh is a pioneer in this evolution, spanning a career in writing for over fifty years. The depth and breadth of her literary creations are unparalleled by any living Arabic novelist. Thanks to Aida Bamia, the English library is enriched by her translations of Khalifeh’s works.

Aida Bamia, a professor emeritus from the University of Florida, surprises us again with another excellent translation of Sahar Khalifeh’s work. This is the continuation of an earlier novel by Khalifeh, Of Noble Origins. Both describe the life of the Qahtan family from Nablus in the West Bank during the tumultuous time of British Mandate (1918–47). In the current novel, the reader sees living in Nablus from the point of view of Nidal, a woman in her seventies who had traveled and lived in many capitals in the world but decides to return to her roots. Nidal meets her first love, Rabi’, and they both reminiscence about their young love for each other. Rabi’ also came back to Nablus after a life of wandering. Khalifeh transcends the local struggles of the Palestinian protagonists to the more universal meanings of loss of everything familiar.

Nablus is Khalifeh’s birthplace and where most of her characters come from. A proud capital of an Ottoman district for about four hundred years, it lost its status after the First World War and its aftermath. It became another provincial town in Palestine and in the Middle East in general, losing its place to the two port cities of Yaffa and Haifa. Khalifeh’s characters move between these cities and Jerusalem. The mobility signifies a society in transition from a traditional agricultural economy to a more modern economy. As Palestinians were struggling with the changing economic and subsequent social and political changes, they were also fighting for self-determination. The spectacular fall of Palestinian society and the dispersal across the region is observed and witnessed in Khalifeh’s novels as a universal loss of “who one is.” Khalifeh successfully transcends the particular to the universal.

Khalifeh’s novel takes us into the Palestinian history of the past century and its encounter with British colonialism, on one hand, and the Jewish settlement project in Palestine on the other. Palestinian protagonists are not the ultimate victims of both. Rather, they are willing agents who interact with both challenges to their identity as well as the right to simply live their lives. By telling the story of the Qahtan family, Khalifeh is telling us the story of Palestine through the life changes, aspirations, and choices of the main characters. Further, to Khalifeh, who holds a doctorate in women’s studies, the urgency of the liberation of women is no less important than the urgency of the liberation of Palestinians from occupation. Self-determination is a right to both women and to the Palestinians as a whole. To her, both go together. Khalifeh resurrects in her novels a society on the verge of dispersal and then its aftermath. Palestinian society was facing the challenges of modernity at the same time that it was clashing with colonialism. The characters depict this struggle successfully.

If there is an Arabic novelist who deserves the Nobel Prize, after Naguib Mahfouz, it is Sahar Khalifeh. The strength of the structure of her novels and the aesthetics of her style are unparalleled by any living Arabic novelist. Thanks to the excellent translation by Aida Bamia, both are rendered vitally in English. I highly recommend reading the novel. Of Khalifeh’s eleven novels, Bamia has enriched the English library with translations of four of them. Not surprisingly, Bamia also translated Naguib Mahfouz into English.

Camelia Suleiman

Michigan State University