The Lost Soul by Olga Tokarczuk

New York. Seven Stories Press. 2021. 48 pages.

New York. Seven Stories Press. 2021. 48 pages.

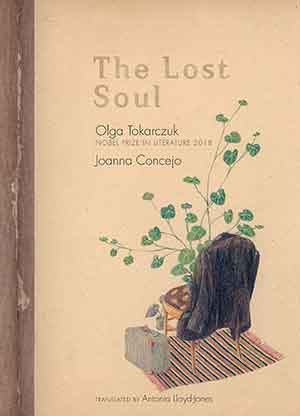

“ONCE UPON A TIME there was a man who worked very hard and very quickly, and who had left his soul far behind him long ago . . .” So begins Olga Tokarczuk’s latest book in English translation, The Lost Soul, and her first book for all ages. It is a beautiful collaboration with Joanna Concejo, a visual artist and fellow Pole, and Tokarczuk’s longtime translator Antonia Lloyd-Jones. The Lost Soul is a simple story about what happens when we are forced to wait for the little feet of our inner child to catch up with the hurried pace of life.

John, as his name suggests, could be anyone. In fact, he is not even sure if he is called John, or Andrew, or Matthew when he wakes up in a hotel room suddenly unable to remember which city he is in or what he is doing there. “All cities look the same through hotel windows,” he thinks. A wise doctor frankly informs him that he’s lost his soul and, while he’s been unaware of the missing soul for quite some time, it is out there looking for him, desperately trying to catch up. Souls live slow, gentle, and unhurried lives, so John is given a prescription to rest and to wait. He finds a cottage on the outskirts of the unnamed city and does precisely as prescribed; “He didn’t do anything else,” Tokarczuk writes.

What follows are pages of Concejo’s timid, delicate pencil drawings: postcards of indistinguishable places, a public park in winter, silhouettes of people walking their dogs or playing ice hockey, a lone figure’s footsteps in the snow, and a child, no more than seven or eight years old. While John waits and the plants in the cottage grow tall and wild, the child wanders on, observing a village dance, playing at the seaside, and gazing at a sunset through a train window. These scenes feel far from the frantic existence John left behind. Is the child unable or just unwilling to witness those moments—dull commutes, board meetings, tennis sessions, late nights working? Or is it John himself, sitting in the cottage, revisiting only the slowest and most serene memories to invite his soul back in? As the child closes in on the present day, Concejo’s grayscale illustrations give way to a burst of color, as a bearded, aged John and his soul meet face to face on opposing pages in a sincerely moving tableau.

Of course, there has never been a stranger time to review a book about slowing down, a year into a pandemic and in the dead of a dark winter lockdown. We don’t really know what John has left behind, only that he lives “happily ever after” through “all the peaceful winters that followed.” Reading, I felt a sad pang of envy for John’s hurried modern life—an ache to see a city through a hotel window, or to look through any window that isn’t mine. Our response to enforced inertia has been an insatiable craving for more: more excitement, more feeling, more lockdown hobbies—anything to keep us from sitting, “day after day, waiting.” But in waiting for his soul, John came to recognize what is “enough” or, as many other fairy tales imply, “just right.”

In a time of uncertainty, stagnation, and grief, Tokarczuk and Concejo offer consolation—that we too might stop and recognize what is enough, endure our own “peaceful winters,” and possibly let go of the craving for more than that.

Hannah Weber

Brighton, United Kingdom