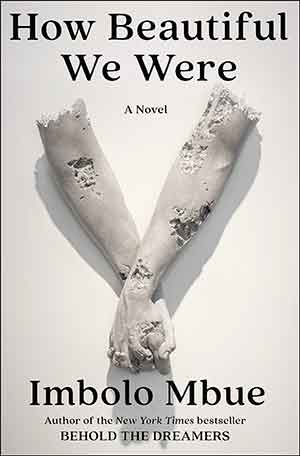

How Beautiful We Were by Imbolo Mbue

New York. Random House. 2021. 384 pages.

New York. Random House. 2021. 384 pages.

HOW BEAUTIFUL WE WERE is Imbolo Mbue’s second novel to be published; however, Mbue started writing it long before her first novel, Behold the Dreamers, appeared. This novel transports readers to the imaginary African village of Kosawa, grappling with the ravages of environmental pollution as a result of drilling by an American oil corporation.

The novel opens dramatically when, at a village meeting with representatives from the Pexton Oil Company, Konga, a madman, captures the car keys of the delegates, steering the village toward an astonishing act of rebellion: holding the Pexton men hostage to exert pressure on the company to reveal what happened to their own men who disappeared when they went to the city to lodge a complaint.

The narrative vacillates between the perspectives of the children who witness this primary act of rebellion and other characters in the village. The dramatic act of collective solidarity initiated by Konga is a sly inversion of Pexton’s strategy of liquidating the emissaries from the village who had demanded better environmental protections. The initial act of rebellion prompts a retaliatory bloodbath against Kosawa and the arrest and execution of several villagers on charges of kidnapping. Already, readers are plunged into cycles of trauma: the original trauma of oil drilling close to human habitat, the lack of environmental protections to preserve the sanctity of water resources, and retaliation when villagers protest.

These traumas are registered most acutely on the Nangi family, particularly Thula, whose father goes missing in the original delegation. Her uncle is then executed without a proper trial for the alleged kidnapping. These early episodes of irrevocable loss radicalize Thula, who is determined to seek justice for her village. She overcomes tremendous obstacles to secure a high school education and then pursues higher education in the US, which leads her to an understanding of neocolonial oppression, capitalism, and environmental justice.

She returns to Kosawa, choosing the solitary path of teaching and activism in her native country. However, even before she returns, she flirts with the idea of violence as a mode of exerting pressure on Pexton. She inspires a group of her age-mates to engage in acts of arson to sow some fears in the minds of Pexton managers. She pours all her energy into building a grassroots movement against His Excellency, the political head of state who has allowed Pexton to drill with impunity. She is able to hire a lawyer to sue Pexton in a US court for reparations. Her brother, Juba, while initially her ally, gradually disassociates from her, choosing instead the easy life, working for the government, and accepting corruption as part of the fabric of life in his country. The novel ends with the shattering of hopes for legal restitution and with yet another episode of violence and tragedy.

Mbue seems to be suggesting that every successive generation in Kosawa is subjected to its own history of failure and a brutal crushing of hope. While this may seem to be a presentation of utter pessimism, what preserves a more hopeful sensibility in the novel is the care with which Mbue depicts the bonds of African village life. The Nangi family is characterized by relationships of mutual care, reciprocity, and nurture. The bonds between family members are lovingly portrayed and stand in contrast to the death and violence surrounding them. The memorialization of these affective bonds is perhaps the call to future generations to continue the struggle against the collusion of neocolonial governments with global capital.

Lopamudra Basu

University of Wisconsin–Stout