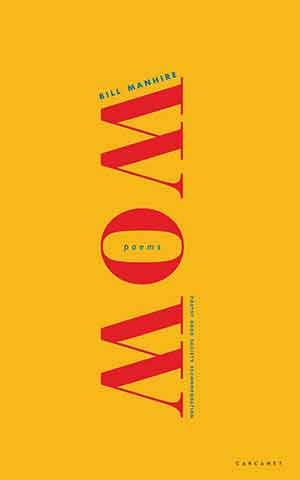

Wow: Poems by Bill Manhire

Manchester, UK. Carcanet. 2020. 88 pages.

Manchester, UK. Carcanet. 2020. 88 pages.

THE OPENING POEMS of Bill Manhire’s new verse collection, Wow, suggest an ecological theme. The first poem, “Huia,” is about an extinct New Zealand bird, which was nearly driven to extinction early in the twentieth century due to hunting for its plumage and agriculture-driven deforestation. The poem, sung in the voice of the vanished bird, has a haunting lyric structure, and its imagery befits its beautiful but doomed subject. The next poem, “Untitled,” continues the theme with its opening line: “This book about extinct birds is heavier than any bird.” The speaker of “Untitled” lifts up “page after page of abandoned wings” and imagines that the book on his lap is a house cat, implying the role people have played in the ongoing crisis of mass extinction. At this point, readers may think they know what kind of book they hold in their hands.

Wow is not limited to ornithology or ecology, however: impermanence is the central theme. Manhire explores time and change, birth and death in poems occasionally humorous, often absurd. There are many masterful poems of loss. “Woodwork” is a poem such as this. The opening subject comes from a story of Dutch students who help build a coffin for their dying teacher. Though inspired by contemporary events, the poem reminds one of Faulkner’s scenes in As I Lay Dying of Cash building Addie’s coffin outside her window. By the time the poem’s couplets come to close, the speaker imagines children everywhere building coffins—a synecdoche for the way one generation replaces another.

Manhire’s regard for passing things is not limited to the animal world. In “Discontinued Product,” a strangely anthropomorphic smart speaker argues like a feeble relative with its owner as its circuitry degrades beyond repair. In “After Lockdown,” the subject is a mechanical dog likewise at the end of its serviceable life. As its owner goes to disassemble it, noting that it had been a good guard dog in its day, the machine tells its owner: “You know I can still talk . . . / I do have feelings.” The title poem uses the ubiquitous noise of baby talk and traces it through life, from the early babble of infants to the awe of discovery in youth to the rambling mumble of the very old and infirm. All of humanity goes along for the journey, and the poem describes those in the middle observing this like passengers getting ready to board a plane. These poems ask what sentience really is and consider where we should draw the line of sympathy. The answer is clearly “as widely as you can.”

The poems of Wow range from lyric and rhyme to sparse, ironic poems. There is enough variety of technique here to demonstrate Manhire’s skill as a poet, but experimentation on the field of the page is not the point, and there’s a voice behind the printed words that makes me wish I could see Manhire perform his work live. Perhaps one day, when the pandemic too has passed.

Greg Brown

Mercyhurst University