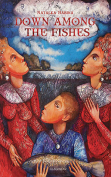

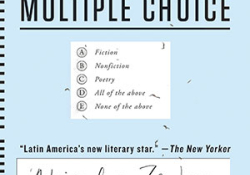

Mis documentos by Alejandro Zambra

Barcelona. Anagrama. 2014. ISBN 9788433997715

If “publish or perish” is an academic creed, Alejandro Zambra abides by “polish or perish.” The eleven narratives included under an ingenious title, which alludes to whatever notion of archive one adheres to, have been published as fiction, as parts of essays or critical notes. Now organized into three sections, each with a common thread, the character studies within each tale also have a cumulative power that makes Mis documentos perhaps the best short-story collection of the last two decades.

If “publish or perish” is an academic creed, Alejandro Zambra abides by “polish or perish.” The eleven narratives included under an ingenious title, which alludes to whatever notion of archive one adheres to, have been published as fiction, as parts of essays or critical notes. Now organized into three sections, each with a common thread, the character studies within each tale also have a cumulative power that makes Mis documentos perhaps the best short-story collection of the last two decades.

In “Larga distancia,” the writer-protagonist’s incipient woes (while he works part-time at a call center) challenge our sympathies, and such imprecise moral ambiguity reminds us that we do not live in a clear moral universe. From the title story to others like “Instituto Nacional” (both the most akin to “autobiografiction”), digital millennial culture is omnipresent, as are hyperarticulate dialogs and concomitant rapid-fire cursing, allusions, and wordplay. Haphazard episodes, flights of fancy, quasi-philosophical musings, and aesthetic digressions, some as humorous extrapolations of millennial generational angst, ultimately lend suspense to each story.

Some reductionist critical expectations hold that today’s Chilean literature needs to at least nod to the obnoxiousness of living after Pinochet, in a nanny state; Zambra does so subtly in “Camilo” and “El hombre más chileno del mundo,” showing that the present is much more complicated, that intergenerational mobility is steady, and that insisting that anything is an icon of a political system is immature. There are also no archetypes, cliffhangers, or preposterous plotting, and when the default surprise ending of traditional narrative is present, it is never overdetermined.

Some episodes and secret histories echo one another, relaying the feeling that unapologetic logic and reason have little place in an era obsessed with ambivalence and popular culture (“Verdadero o falso” and “Yo fumaba muy bien”). This approach is abetted by some lyrical depictions, as in “Hacer memoria.” To paraphrase Churchill, these stories can be a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is generally watching the author calibrate what appear to be his aesthetic commandments rather than a particular goal for each story.

This superb collection belies assumptions that Zambra, his generation’s lightning rod, is a minimalist. This is because the interlocking element is the literary world into which most of the characters wander, within a larger metafictional frame with no user’s manual for dealing with learning and teaching, maturing, compulsions, soccer, a globalized world, minor secrets and vices, sex, or “the literature of the parents,” whether their elders’ or old literary masters’.

For Zambra, genre boundaries are not impervious, and the devil is in the details of how he tweaks them by using the contemporary aesthetic values in which he is embedded, without making them appear as a symbol of unconventionality or capitulating to older aesthetics. He is brilliant in achieving that goal without loopy obsessions or by letting regional settings restrict the relentless joy he manifests in every story.

Will H. Corral

San Francisco