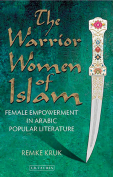

The Warrior Women of Islam: Female Empowerment in Arabic Popular Literature by Remke Kruk

London / New York. I. B. Tauris. 2014. ISBN 9781848859272

We have all heard of The Thousand and One Nights, but stories outside this collection are a different matter, even for specialists, the genre of popular epic narrated by professional storytellers having been rather looked down upon by scholars and hence making only brief appearances in literary histories. Remke Kruk has most usefully prepared accounts of, with occasional translated extracts from, eleven tales recounting the chivalric adventures of various heroes. Or rather, if the word is permissible today, heroines.

We have all heard of The Thousand and One Nights, but stories outside this collection are a different matter, even for specialists, the genre of popular epic narrated by professional storytellers having been rather looked down upon by scholars and hence making only brief appearances in literary histories. Remke Kruk has most usefully prepared accounts of, with occasional translated extracts from, eleven tales recounting the chivalric adventures of various heroes. Or rather, if the word is permissible today, heroines.

Popular epic, sīra sha‘bīya, has existed in the Arab world from the Middle Ages and survives to this day (Kruk heard a Moroccan storyteller narrate one of her selected stories in 1997). The tales center on the deeds of warriors endowed with implausible strength, endurance, and, often, nobility who fight with sword, shield, and lance, win cities and provinces for Islam, make daring escapes, and fall in love. The stories switch focus from the trials and triumphs of one fighter to those of another, Kruk interestingly comparing this manner of narration to the one employed by soaps. Here, however, the chivalric women warriors will refuse marriage except to a man who can defeat them in battle or will distract their opponents’ attention by the sudden revelation of their physical charms. Extracts from the story of Dhāt al-Himma take up three chapters, succeeded by two from the Sīrat ‘Antara and others.

Kruk deserves our thanks for making available to a general and even scholarly audience what is effectively a new literary territory for the West. Her authority in the area seems unassailable, and she writes pleasantly (although she does occasionally have trouble with subject-verb agreement). She makes the necessary gender point that “given [that] these stories were composed by men, they clearly reflect male anxieties and desires,” without descending into jargon or contumely. The book is well designed and illustrated, engagingly including the cover of an Egyptian book on Dhāt al-Himma, which “recalls Xena, the warrior princess from the American television series popular in the Middle East in the 1990s,” an instance of Western influence on Arab perception of their popular stories that, in The Arabian Nights, have so formed our imaginations.

M. D. Allen

University of Wisconsin, Fox Valley