“A Species of Magic”: The Role of Poetry in Protest and Truth-telling

(An Israeli Poet’s Perspective)

Israeli poetry of protest is a relatively new phenomenon, even as it emanates from an ancient Jewish tradition of debate and dissent. Rachel Tzvia Back considers the power of poetry in general, and in her region specifically, to protest and speak difficult truths in the face of ongoing conflict and lies.

Truth is such a rare thing; it is delightful to tell it.

– Emily Dickinson

1. Language

I start from the obvious: we live in a time when language is willfully, often maliciously, misused and manipulated to serve the ends of those in power. We live in a time when in countless ways language has become a tool of deception and demagoguery. Of course I do not think that our times are unique in this abuse of language; there are abundant examples throughout history of how language was skewed and slanted to serve a particular agenda, often the persecuting spirit of the day. And yet, because of the easy access to and proliferation of language mediums provided by the Internet age we live in, it seems to me that the decay of language has accelerated, a decay manifesting itself in the ever-widening gap between signifier and signified, between what is said and what is meant.

In the Israeli context, within the mind- and soul-numbing reality of decades of military conflict, we live with terms that deliberately obfuscate the full horror of their intent, terms such as “targeted liquidations,” “administrative detention,” “reasonable collateral damage”—or terms whose sole purpose is to perpetuate a status quo of self-righteous posturing, violence, and conflict.Language, as such, has become for many suspect; for others, language has become the net of lies in which they allow themselves to be entangled.

Within the conflict of my region, this language-bind has presented significant challenges and obstacles for anyone working for civil rights, for social change, and, above all, for peaceful resolutions. The terms of engagement have been set by others: the “us”/“them” paradigm is firmly in place; the “right”/“left” labels are fixed. The polarization is so deeply entrenched, the chasm between positions so wide, that often it seems as though saying anything that can be heard by “the other side” is doomed to failure even before one begins. The image that comes to my mind is of the Shouting Hill up on the Golan Heights, near the Druze village of Majdal Shams. Two groups—Druze families and communities divided by war—are separated by barbed-wire fences, by an open expanse of no-man’s land, and by soldiers. Traditionally, the two groups, each on its own side, have come to the Shouting Hill to shout across the distance—to tell news of family births, weddings, deaths; two sides of one family, divided, shouting down the winds.[1]

When any activist for political change speaks out, the image I see in my mind’s eye is of a person on the Shouting Hill shouting into the wind, while those on the other side turn their backs, cover their ears, and walk away.

The analogy I am drawing here, between the two sides of a Druze family on the hillside and the two sides in almost any contemporary political or social debate, is an analogy that breaks down, of course, at one crucial point: on the Shouting Hill, both sides want to hear what the other side has to say; in the two sides of Israeli politics and society, the two sides want to stay deaf to each other. When any activist for political change speaks out, the image I see in my mind’s eye is of a person on the Shouting Hill shouting into the wind, while those on the other side turn their backs, cover their ears, and walk away. The words spoken drop into the no-man’s land in between: a speech act with no listener fails as a speech act and becomes nothing.

2. Poetry

And so I come to poetry—which is, of course, ironic, as we live in a time when poetry is so often thought irrelevant. One may consider it such, but I see it otherwise. Because poetry has been marked as marginal, it has a certain advantage—let’s call it the advantage of the underdog: the resistance of the listener is less pronounced; the listener hasn’t already decided not to hear. But poetry has other advantages, intrinsic attributes and characteristics that mark it as a useful tool for awakening a social conscience, for political activism and protest.These attributes could be called many things, but I have named them as follows: (1) the drive toward accuracy and truth-telling; (2) the personal accountability of the poetic, and (3) the magic of intertwined meaning and music. It is these three attributes—a poetic holy trinity, if you will—that I will elaborate here.

A natural by-product of striving toward accuracy and truth-telling in poetry is, I believe, the taking of responsibility, the personal accountability of the poet.

Accuracy (that strives toward truthfulness): This first attribute takes us back to the aforementioned abuse and misuse of language; unlike political speech, poetry cannot afford to misuse language, for in misusing language, it negates itself and its very reason for existence. Poetry as a language art exists on its accuracy; less than accurate is unacceptable to the poet. “Pray for the grace of accuracy,” writes American poet Robert Lowell, a line every poet might speak before she puts pen to paper, an invocation in the ancient tradition of the Greek bards who appealed to the Muse before embarking on their own epic compositions. This appeal to a force greater than ourselves (though found within ourselves) acknowledges at the outset that the poetic has embedded in it a sacred essence, its truth-telling capacity. World War I poet Wilfred Owen wrote the following: “true poets / must be truthful”—a seemingly tautological statement that in fact articulates clearly the test of a true poet: it is he, it is she, who tells the truth—whatever that truth might be.

A natural by-product of striving toward accuracy and truth-telling in poetry is, I believe, the taking of responsibility, the personal accountability of the poet—the second attribute of our poetic holy trinity. The poet stands bare with his words and is responsible for them. The notion of taking responsibility for one’s language usage is, of course, an element all but absent in public and political discourse today; as such, it is an element that sets poetic discourse apart. The poet labors long and hard on exact articulation, as she knows that each word creates a world. Indeed, in the very first chapter of Genesis, it is the spoken word that makes our world: “And God said, ‘Let there be light.’” A millennium or so later, the author of the Gospel of John echoes the Old Testament creation story and accentuates the centrality of language in the opening verse of that book, which reads as follows: “In the beginning was the Word, and the word was with God and the word was God.” Libraries of theological tracts have been written on this verse, all fascinating but far outside the focus of this essay. For my focus here, I read the verse quite simply and directly: the word is imbued with divine power.

As a poet, wielding the written word, I am responsible for what the word may do. If the word—the verse, the image, the poetic line—falsifies, fails at telling the truth, I am at fault, I alone have failed. Thus, aware of both the power of the word and my singular responsibility for my words, I approach language with something akin to reverence. The semireligious terminology is deliberate; the path from poem to prayer is a short one. Time on earth is short, and the poet, like the religious supplicant, knows each word must count. As nineteenth-century poet Emily Dickinson wrote in an oft-quoted letter, “I hesitate which word to take as I can take but few, and each must be the chiefest. But recall,” she continues, “that Earth’s most graphic transaction is placed within a syllable, nay within a gaze.”

The final attribute of the poetic “holy trinity” is an attribute that all but defies definition. In my university Introduction to Poetry classes, I spend the first session asking the students, “What is poetry?” The answers they offer are many; all are partially right and all are inadequate. Poetry is short verse, they say, it is rhymed, it is imagistic, it is this, that, and the other. After they have exhausted themselves and the board is covered with their definitions, I offer them a very brief definition I found many years ago in dictionary of literary terms: “Poetry: noun; a species of magic.” A species of magic . . . Poetry as a language art is only part grammar and syntax—that is, it is only partially meaning and content. It is also music, incantation, rhythm, sensations. Let’s not forget that the first poets, the Israelite King David and the Greek Orpheus alike, were first of all master musicians.

It is, I believe, poetry’s sound and music, as they interact with and impact on meaning, that produce the magic the dictionary referred to. Undoubtedly, it is these visceral effects of poetry that T. S. Eliot was referring to when he said that “the poems I have loved the most are those I have understood the least”; Eliot foregrounds in this enigmatic statement that something in a poetic text which may elude intellectual understanding even as it impacts directly and compellingly on the reader’s heart and spirit. I see the power and potential of poetry residing in that realm, in the ways a poem may touch our emotionally numbed selves and thus inspirit, inspire, and even transform us.

All these attributes together place the poet in a unique position for speaking out against the wrongs of the day, for channeling the embedded strengths and natural propensities of his or her art also for protest and resistance. I am not saying this is what a poet should do—I don’t believe in prescriptive tasks set before the artist, as such directives most often lead to inferior art. And yet I do believe that in the interface between what Wallace Stevens termed “the pressure of reality” and the wonders of imagination and talent—in the ongoing interplay between the personal and the political—the true poet, being truthful, may offer us alternative versions of and even redemptive visions for our troubled world.

3. The Role of Poetry in Israel

I focus my words now on the role of modern Hebrew poetry in Israel, and on the effects of the aforesaid poetic “holy trinity” in precipitating change. Obviously I am referring here to the poetry of protest and dissent, the voices that challenge and resist the monolithic mythological constructions of our identity. “Literary resistance,” states Tel Aviv University professor Michael Gluzman, “begins with a questioning of the unspoken assumptions of the center”—“the unspoken assumptions” that have, to no small degree, contributed to our inability to exit deadly cycles of conflict and warfare. The impact and importance of such literary resistance cannot be overstated in a country as small and as young as Israel, where the literary voices have traditionally served an important role in collective identity formation and the nation-building process.

Indeed, the Hebrew poets, through the better part of the twentieth century, were expected to speak the single narrative of the day, a narrative implicitly reflective and supportive of official government policies, which were—and too often still are—seen as synonymous with the desires of the people. Hebrew even has a term for this literary phenomenon: shirah meguyeset (mobilized poetry), poetry that speaks in the name of the nation, carrying the patriotic flag into battle. (The military terminology is hardly surprising; military language and military concepts have infiltrated and affected every aspect of Israeli life.) As a direct and predictable outcome of this phenomenon of mobilized poetry, the early modern Hebrew poets taught in schools, published in newspapers, anthologized and canonized — poets who were identified as “national poets” — were those who spoke the Zionist narrative most passionately and categorically: the absolute narrative of Return to the Homeland, of being a Chosen People, of the singular and always-righteous struggle of early Statehood, and so on. The national poets, from Bialik to Amichai, were the poetic voices heard in high and popular cultures alike, reflecting and creating the evolving national sensibility.

What were not heard, what were pushed to the margins, were the other voices, the voices that contended with what Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid termed the “difficult knowledge” of the day. Of course there were, and still are, many types of “difficult knowledge” in Israeli society: “difficult knowledge” of gender, ethnic, and racial inequalities and forms of oppression, all supported by the phallocentric and Eurocentric power structures of the state. But my concern here is specifically on Israeli-Palestinian relations, and in that arena the “difficult knowledge” included the fact that the land was not empty when the first Zionists arrived and that an entire people was dispossessed as a direct by-product of the formation of the State of Israel. Thus, poet Avot Yeshurun’s challenging 1952 poem “Passover on Caves,” which spoke explicitly of the great losses suffered by the Arabs of Palestine, was seen as “transgressive and revolting, an emblem of betrayal” (Gluzman).

Earlier, in a very public literary debate, Lea Goldberg was taken to task for her adamant refusal to be swept into the militaristic zealotry of the day; her resistance expressed itself in her refusal to write “war poetry” and her clearly articulated insistence on writing love and nature poetry during those very dark days. As an apparent response to the debate and to the criticism leveled at her, Goldberg composed one of her most famous and most beautiful poems—a poem that I read as insisting there are alternatives to war and violence. The untitled poem goes as follows:

And will they ever come, days of forgiveness and grace,

when you’ll walk in the fields, simple wanderer,

and your bare soles will be caressed by the clover,

or wheat-stubble will sting your feet, and its sting will be sweet?

Or the rainfall will catch you, the downpour pounding

on your shoulders, your breast, your neck, your head.

And you’ll walk in the wet fields, quiet widening within

like light on the cloud’s rim.

And you’ll breathe in the scent of the furrow, full and calm,

and you’ll see the sun in the rain-pool’s golden mirror,

and all things are simple and alive, and you may touch them,

you are allowed, you are allowed to love.

You’ll walk in the field. Alone, unscorched by the blaze

of the fires, along roads stiffened with blood and terror.

And true to your heart you’ll be humble and softened,

as one of the grass, as one of humankind.[2]

While the poem was ultimately embraced by the establishment (and somewhat sentimentalized in the process), I still read it as a poem protesting the militant norms of her, and our, day. The singular “you”—the female at in the original Hebrew—walks alone along roads “stiffened with blood and terror,” and instead of responding to the blood and terror with vengefulness, hatred, or a renewed call to arms, the “you” is instead humbled and softened. Thus, Goldberg offers her readers a new paradigm, intrinsically humanistic, implicitly pacifistic. This paradigm, unconventional and even subversive in Goldberg’s day (and in ours too), insists on humankind’s commonality in place of nationalistic / Zionistic / Jewish exceptionalism; this paradigm locates personal redemption in the embrace of a universal community, in the understanding that we are all one humankind. Indeed, in the aforementioned public literary debate, Goldberg stated clearly that she saw it as her role as poet to “remind humankind, every moment and every day, that the opportunity to return and be human is not lost.” The dissent of this statement and of her poetry resides in her implicit insistence on the humanity also of the Other, of the stranger, even of the enemy.

Goldberg and Yeshurun both offered poetic dissent in a pre-1967 context; with the Six-Day War and the ensuing occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, the need for poetic dissent only grew, and continues to grow. In its early years, the Occupation was made invisible to the Jewish Israeli and international communities, whitewashed by the authorities, by the media, and by vigorous nationalistic propaganda. Hebrew poets, too, were party to the blindness, complicit in their silence; for almost two decades of occupation, there were few poems of protest, few poems articulating the realities of military rule in the West Bank and Gaza and challenging the government’s oppressive policies. However, by the mid–1980s, Israelis in general and artists specifically finally began to awaken to and acknowledge the horrors of the continuing occupation and its many crimes, jolted awake primarily by the Palestinian uprisings known as the intifadas.[3] Vibrant and vocal poetic protest ensued.

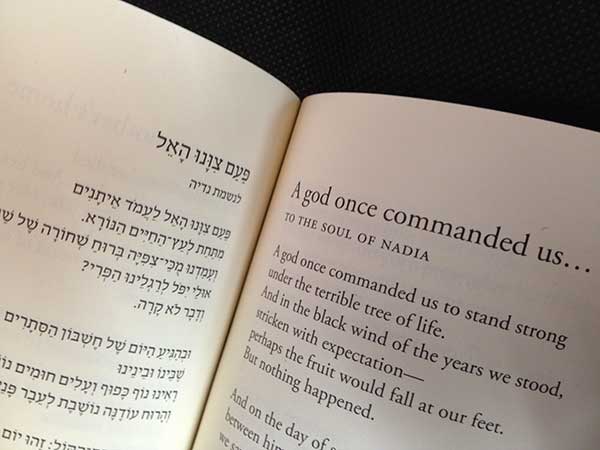

I offer you one milestone publication in the evolution of Hebrew protest poetry, poetry that challenges the status quo, articulates ethical dilemmas, and tackles the “difficult knowledge” of the day. This publication was a 2005 Hebrew anthology of protest poems, published in its English version in 2009 and entitled With an Iron Pen: Twenty Years of Hebrew Protest Poetry.[4] The English version includes eighty-eight poems by forty-two Hebrew poets, poems protesting in myriad ways and in multiple voices Israel’s policies of occupation and their impact on Israeli and Palestinian societies both. The poets in the anthology range from the well known and prizewinning to newer and younger voices; from the politically identified to poets who have traditionally written on other subjects. The range is impressive and important to note: this is not an anthology of a marginal group, not a few leftist poets; rather, the collection offered in its Hebrew original, and continues to offer in the English edition, a significant representation of contemporary Hebrew poets, speaking in rage, shame, and despair over crimes committed in their names.

The ability of the Hebrew poet to access and integrate the biblical, particularly in these politically hued writings, situates the poems within an ancient, and very Jewish, tradition of vigorous debate, dialogue, and dissent.

The title of the collection is taken from a verse from the book of Jeremiah, the archetypal prophet of rage, and reads in full as follows: “The sin of Judah is written with an iron pen, engraved with the point of a diamond, on the tablets of their hearts.” Indeed, the biblical is ever-present in this collection of poetic protest, a scarlet thread that runs through the texts; the ability of the Hebrew poet to access and integrate the biblical, particularly in these politically hued writings, situates the poems within an ancient, and very Jewish, tradition of vigorous debate, dialogue, and dissent.

I share with you one poem from With an Iron Pen, a poem that foregrounds the biblical. Through a dialogue with a foundational biblical tale—Joseph and his coat of many colors, a coat later stained by his brothers with the blood of wild beasts—this poem insists we face the beastlike nature of our current acts and our policies. Accompanying the poem is a black-and-white photo of a little boy, maybe seven or eight; he’s lying bare-chested on what looks like a stretcher, his arms lying outstretched, and in his side there is a ragged black wound—a bullet wound. His beautiful black eyes are open, unmoving. The poem by octogenarian Hebrew poet Aryeh Sivan is appropriately titled “Ani Mokheh,” meaning “I Protest,” but the words also mean, much more prosaically, “I Wipe Off.” A single stanza, the poem reads:

I wipe the dust off my books

with a small t-shirt, an old t-shirt

which was once my son’s. We have

more dust this summer than last,

and its composition is different too:

mixed in it are pieces of plaster and paint

maybe from the houses that were blown up. In any case

after an hour or so of dusting, stripes

of many shades

appear on the garment. Normally

I would think of Joseph

the gifted and beautiful boy, the wise boy who knew how

to extricate himself so tactfully

from every trouble that befell his family, the boy who dreamt

of wheat stacks, the boy who went to Shechem

to tend his sheep. But today

I can’t get out of my mind

the picture of a different beautiful boy

from Shechem: Here he is before you, lying motionless,

and the hole in his chest is not

from the teeth of a wild beast.

In the palimpsest of images—the speaker’s son, overlaid by an image of biblical Joseph, overlaid finally by an image of a dead Palestinian boy, killed in a crossfire it seems—the poem insists on the similarities and the terrible differences between the three boys, insists on our acknowledging the lies we tell ourselves to justify unacceptable deaths, insists on our not looking away, not from the black-and-white photo, not from the heartbreaking image of this little boy from Shechem, a new Joseph (or Yusuf) who is not saved and not redeemed.

I situate my own writing within this category of Israeli protest poetry. Being a poet of protest was not something I set out to be; it evolved, together with the circumstances around me. Particularly through the second intifada, when the daily deaths on both sides of the conflict felt close up and personal, the need to speak out against the violence rose in me with a great urgency. My second full-length poetry collection, entitled On Ruins and Return (2009), was devoted almost in full to what might be termed political poetry, though the poems in the book are no less personal for their dissenting hue. Stevens’s “pressure of reality” threatened to overcome me in those years, with the suffering and deaths, especially of children, haunting me; writing these poems was a way to contend with that pressure, that terrible reality. I have felt that my protest, like Aryeh Sivan’s, is in the unflinching gaze of the texts, in the refusal to look away, in the insistence that the reader look too. Through the poems, we see what we are, what we’ve become, and what we’ve inflicted on others. I share with you this poem that originated from a newspaper item; the opening line of the poem was the headline of that newspaper item, and the next stanzas are poetic renditions of what the item described, then in italics what I saw in my mind’s eye.

Press Release

January 26th 2004

Nobody was killed in al Nabi Saleh tonight

Only

500 old and young

forced to stand hours in the cold

in the middle of night

in the rain

in the range

of snipers on the watchtower

and the children

in flannel pajamas with coats thrown over

thick in layers too loose and bulky

to hold sweet calves baby buffalo

their feet pushed hurried

into shoes without socks their small

finger bones cold as clay brittle in their

parents’ hands their

faces

still soft in sleep but eyes waking would be

eager or earnest now pulled

screeching jeeps and wild searchlights

scattering sharp-cut

lightbeams

like diamond treasures dreams in the dark

megaphones calling out calling names cutting

silence into strips and coloring

their racing hearts

crayon black

in the middle of the night

in the rain

in the range

of snipers

the children

thinking they dream.

In his beautiful 2007 essay “Writing in the Dark,” David Grossman argues that “the language with which citizens [living in] a sustained conflict describe their predicament becomes progressively shallower the longer the conflict endures. Language gradually becomes,” he continues, “a sequence of clichés and slogans.” I would add to Grossman’s terribly apt and pertinent observation the following: together with the language, the hearts of citizens living in a sustained conflict become progressively shallower, numbed and refusing to feel. I see this all around me, and I feel this within me; so I turn to poetry. Poets have it within their ability to expand hearts and to deepen emotional engagement. Poets of protest, in particular, can help us open what Susan Sontag termed “avenues of compassion,” avenues that must be opened if we are ever to find our way out of violent conflict. I don’t imagine poetry to have powers it does not; and yet I offer here this very preliminary consideration of Israeli poetry of protest also as a suggestion that in educating ourselves and our children to the complexities of Israel, and in the ongoing struggle for a peaceful resolution in Israel/Palestine, poetry may serve as a useful tool, an alternative mode of communication that can, in its own fashion, contribute to change.

Finally, I close with a New York Times letter to the editor from February 2003—more than a decade ago and still relevant. I was on a reading tour in the US then, and America was busy preparing to embark on its terrible misadventure in Iraq. An article was published in the Times about dissenting voices among poets, and a fierce debate unfolded in the letters to the editor as to whether poets had anything to contribute to the political and security considerations informing national policies. An American writer named Maerwydd McFarland wrote a response that spoke profound truths for me: I cut it out and have carried it with me since, almost as if it has totemic powers. I end my essay with her words:

Poetry is a defense against darkness;

when we contemplate something as

profound as killing other people to

achieve an objective, poets have an

obligation to give voice to doubt.

To be on the brink of war is to have failed utterly at imagination.

To consider dropping bombs on children or flying hijacked planes into buildings is to be less than fully human.

The words of poets remind us that there are better choices.

Misgav, Israel

Author note: An expanded version of this essay was delivered as a public address at the Valley Beit Midrash of Phoenix, Arizona, and at the University of Miami, both in February 2013.

[1] A powerful cinematic portrayal of the Shouting Hill can be found in the movie The Syrian Bride (2004; Ha-Kalah Ha-Surit), directed by Eran Riklis.

[2] From Lea Goldberg: Selected Poetry and Drama, Rachel Tzvia Back, tr. (Toby Press, 2005), 76. This poem in its Hebrew original was put to music and famously sung by popular singer Chava Alberstein.

[3] The First Intifada began in December 1987 and continued until September 1993, when Israel and the PLO signed the Declaration of Principles, which began the Oslo Accords. With the collapse of the peace talks, the Second Intifada (also known as the al-Aqsa Intifada, after the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem where it began) erupted in September 2000 and continued until February 2005. Over three thousand Palestinians and one thousand Israelis were killed during this period of intensified violence.

[4] The Hebrew original, entitled Be’et Barzel, was edited by Tal Nitzan and published by Xargol Press. The English version, edited by Rachel Tzvia Back, was published by SUNY University Press in 2009.