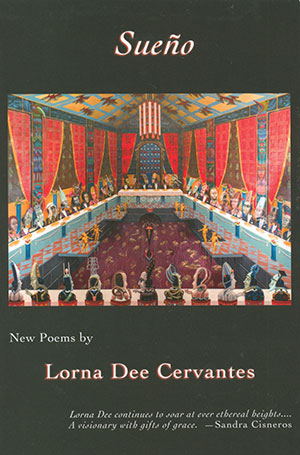

Sueño: New Poems by Lorna Dee Cervantes

San Antonio, Texas. Wings Press (IPG, distr.). 2013. ISBN 9781609403102

In Sueño: New Poems, Lorna Dee Cervantes invokes the song of storytelling, both in a literal lyrical sense and also through the unconscious, cerebral act of dreaming. It is through dreams that the elevated metaphorical truths are rooted out. The same can be said for Cervantes’s latest collection of poetry, which derives from a mighty river of personal and culturally collected memories. She builds her poems with blue-collar grit, the spirit of the migrant farmworker, the buzz of neighborhood platicas, the dream tales of ancestors, and, as always, with language imbued with the salt of the earth.

In Sueño: New Poems, Lorna Dee Cervantes invokes the song of storytelling, both in a literal lyrical sense and also through the unconscious, cerebral act of dreaming. It is through dreams that the elevated metaphorical truths are rooted out. The same can be said for Cervantes’s latest collection of poetry, which derives from a mighty river of personal and culturally collected memories. She builds her poems with blue-collar grit, the spirit of the migrant farmworker, the buzz of neighborhood platicas, the dream tales of ancestors, and, as always, with language imbued with the salt of the earth.

In “The Latin Girl Speaks of Rivers,” Cervantes channels Langston Hughes when she writes the story of Woman. She writes of trauma and of writing for healing when she says, “When I wrote about the serpentine / river I was really writing about / a rape.” She goes on to meditate, “I was writing my heart out. I was / writing myself back in.”

These are poems made in the image of the divine. They are smoke-embraced little ofrendas, offerings to those who have walked before us as well as to the living stories, the rape and oppression of a people and then the birth/rebirth of life. Cervantes is an iconic Chicana/Native American poet, and her literary work was a pivotal voice in the rise and sustainability of the Chicano and Indigenous literary movements. Both artist and activist, her current writing is still necessary, politically charged, and absolutely relevant.

In her poem “A Chicano Poem—for Librotraficante,” Cervantes re-sponds to the Arizona Education Department’s ban of Mexican American literature and other ethnic books in the public classroom. Cervantes declares, “They burned the sacred codices and the molten goddesses rose anew in their flames.” She will not allow the reader to forget past transgressions put upon people of color; therefore, she scribes with the tenacity of a five-alarm fire against current attempted oppressions.

And it is in the language of the mestizaje that she sings the loudest. Her voice is ever-changing, forever in between, shifting like patterns in the sand yet always ringing with the clear bell of truth. Her poems are the dialectical celebration of the colloquial word, and they continue to validate multilingualism as an intersection of culture within the American poetic landscape.

In Sueño, the reader will find that Cervantes’s penchant for lyricism is still finely intact. It is a type of subconscious drumbeat for the reader, and the poems beg to be read aloud. Who wouldn’t want to recite, “He could make love like a 4-barrel / carburetor on a ’72 Chevy / Camaro. Man, he could go. Pumping up / the pistons, discharging with a growl” from the aptly titled “The 4-Barrel Carburetor on a ’72 Chevy Camaro”?

Cervantes is the original bad-girl poeta. She is a spell-casting code-switcher who asserts her indigenity in verse. A voice for many, she is both payasa (clown) and queen bee. Sueño, her fifth major collection of poetry, is a triumphant manifestation of all these gifts, a wonderfully charged volume that makes the reader think and, most importantly, feel.

Jessica Helen Lopez

University of New Mexico