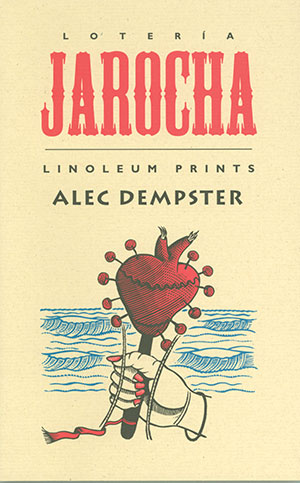

Lotería Jarocha: Linoleum Prints by Alec Dempster

Erin, Ontario. Porcupine’s Quill. 2013. ISBN 9780889843622

Alec Dempster’s Lotería Jarocha brings together two Mexican folk traditions, the son jarocho and the lotería. From Veracruz, Mexico, the son jarocho is a type of music that is sung and danced to while performed on a combination of indigenous and European instruments, while the lotería is a Bingo-like game played by members of the community.

Alec Dempster’s Lotería Jarocha brings together two Mexican folk traditions, the son jarocho and the lotería. From Veracruz, Mexico, the son jarocho is a type of music that is sung and danced to while performed on a combination of indigenous and European instruments, while the lotería is a Bingo-like game played by members of the community.

Lotería Jarocha is a collection of sixty block prints corresponding to a son jarocho, each with an accompanying prose description. The descriptions and the illustrations are whimsical. For example, “Cascabel,” which means “rattlesnake” in English, describes a son that includes elements of flamenco while incorporating a musical instrument sounding like a snake’s rattle. Dempster’s linoleum block print illustrates the musical instrument, but instead of appearing as a rattlesnake’s tail and rattle, it has the shape of a human heart. The son itself incorporates elements of seventeenth-century Andalucian Spain and a passionate dance performed by women.

Lotería Jarocha reminds one of the deeply liberating and subversive nature of folklore and folkloric production. Subversion occurs on several levels. An example is “El Jarabe Loco” (The crazy elixir), a son that can be dated back to the seventeenth century with lyrics that refer to an elixir created by Lucifer to revive the dead. The idea that the underworld generates life is profoundly subversive. So, too, is the practice of performing this son, which encourages anarchic sessions that could go on for hours, where singers improvise.

Folklore fashions a unique collective culture and unites a community with its songs, patterns, art, and beliefs. For example, “El Fandanguito” (The little fandango) is not just a son but also a dance form that provides the foundation of many of the characteristic sones jarochos. While the fandango clearly hails originally from Spain, once arrived and situated in Veracruz, the son was appropriated and modified and continues to evolve and reflect new generations.

In addition to the sixty prints and descriptions of sones, Dempster’s book comes with a CD collection of recordings of sones, some with traditional lyrics and others with new ones written by Kali Niño. Written and performed by both Dempster and Niño, the songs allow the listener to hear the intersections of cultures that come together in the sones and the humor and ironies expressed both in lyrics and in the way that the European, African, and indigenous melodies, harmonies, and rhythms comment on the original.

Dempster’s collection of songs, linoleum prints, and prose descriptions create an amazing reminder that it is an error to treat folklore as simply sentimental material to be preserved as cultural history. Lotería Jarocha joyously posits folklore as resistance to a monolithic way of thinking or expressing oneself and an embrace of community and cultural diversity.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma