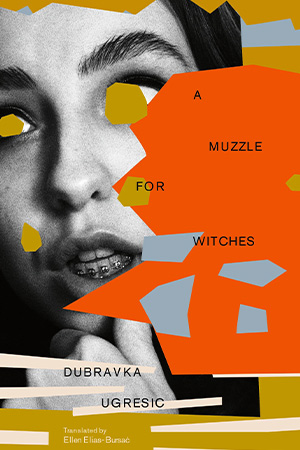

A Muzzle for Witches by Dubravka Ugrešić

Rochester, New York. Open Letter. 2024. 133 pages.

Rochester, New York. Open Letter. 2024. 133 pages.

The groundbreaking novels and incisive cultural critiques of Dubravka Ugrešić have won major prizes in eastern Europe and the West (the Neustadt Prize, Serbia’s Nin, and many more), and Ellen Elias-Bursać has again well rendered her sharp, witty style. First published in 2023, the year of her death, Muzzle has a somewhat circular shape that proceeds organically from the questions of lit-crit interviewer Merima Omeragić and interweaves Ugrešić’s past with that of Yugoslavia, the waning of global culture, and the history and possible future of literature.

While offering few new insights, Muzzle tersely revisits Ugrešić’s central concerns, revealing how the rawest voice of Croatia’s “witches” (so-called for their infamous antiwar positions and the public harassment that led to their exile) became internationally known despite her “muzzle.” Even in her dying, her raw, ironic voice dares women globally to weaponize theirs.

To Omeragić’s first question about what a male Croatian critic meant by Ugrešić’s “strangely deformed optics,” the writer replies that from birth she saw differently from others. Under Croatia’s nationalist identity laws, which reinstated the “blood and soil” of the fascist World War II Ustaše, only those with pure blood gained citizenship. This othered Ugrešić’s Bulgarian mother and rendered her child impure. “Excommunicated by nationalism,” Ugrešić developed a view from the margins.

Ugrešić has long indicted a male trifecta—patriarchy, nationalism, and capitalism—for suppressing women, promoting wars, and eroding cultural standards. Moreover, she holds, patriarchy births “patriotism,” rooted in the nationalism that fueled the “Homeland War” with Serbia and Bosnia. And, as her life underscores, those who defy it face dire consequences. For like other global dissidents, when she and her fellow “witches” raised their voices against the war, male-run institutions—e.g., the government, universities, media, the cultural elites, and publishers—fiercely attacked them.

Tracing patriarchy’s roots, Ugrešić cites Adam and Eve as example, exiled and othered because of Eve’s “sin.” As she notes, various orthodoxies and societal institutions inculcated the concept that women, embodied in negative tropes like fox and witch, could never be trusted. But if cultures viewed women as wily and dangerous (literalized in witches’ muzzles, a medieval torture for women who overstepped their bounds [see WLT, Sept. 2016, 36]), global folklore often recast such tropes as necessary antidotes to misogyny. Alas, to survive, women became complicit in their fates, adopting the role of “waitress”—to serve men and fulfill their fantasies.

Capitalism, meanwhile, supplied women the tools to enhance their bodies and, thus, to attract and keep their men. Whether bound Chinese feet or painful high heels, cosmetics, fashion, or potentially dangerous plastic surgeries, they adorned and even risked harming themselves to raise their worth in men’s eyes. And war, of course, objectified women as booty, ripe for abuse, to shame enemies whose women were their most valuable possessions.

Leaving the battlefield, Ugrešić holds that the same trifecta has diluted both linguistic and aesthetic standards. Post-Bosnia, the new nations carved from Yugoslavia signed a “Common Language Act” to retain Serbo-Croat. But all decided thereafter to embrace their own “national” languages, creating four new dictionaries. Croatian nationalists purged thousands of books written in Serbo-Croat or by non-Croats, which sometimes produced conundrums, for example how to deal with Yugoslav Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić.

Regarding women writers today, Ugrešić maintains that they require an influential male, a “paterfamilias,” to bring their works to the male-dominated media and publishing spheres. Given this reality, women often fear to threaten the male establishment, embracing, instead, traditional male standards endorsed by government, bureaucracy, and society: “the poetics of compliance.” She here mentions Stalin’s infamous call to Pasternak, and the ensuing arrest of Mandelstam, who employed his own poetics. And she views the birth of women’s literature as “a drastic infantilization of global culture” that relegates women further to the margins. Deriding women’s writing as “kitchen literature,” men permit them entry into the literary realm, but only as second-class citizens.

Mourning the loss of “something in the past that was called Literature,” Ugrešić scorns the rise of “hagiographies . . . the wedding of democracy and digitalization.” Oblivious to language, style, or craft, “selfies” offer speedy, “relatable” reads in place of art. Now, she suggests, “the mighty Market controls all.” As the number grows of “multi-task enthusiasts” who practice “splendid self-marketing,” using all available tools to enhance visibility and craft public personae, authors come to matter more than content.

Ugrešić writes not from “the cozy nest of national literature” but from exile, both a boundaryless home and a process. From there, she predicts that the future of literature lies “underground,” in revolts against standardization and “marketability,” where language again regains centrality, and people become “living libraries,” as in Fahrenheit 451. Finally, she hopes for a “transnational” literature that erases borders, eschews ethnicity, and promotes “a perestroika of literary values,” as she herself has practiced all these years.

Professor emerita at North Carolina A&T State University, Michele Levy has published on major Russian and European writers and, since 2000, on postcolonial and postimperial issues in Balkan culture.

Professor emerita at North Carolina A&T State University, Michele Levy has published on major Russian and European writers and, since 2000, on postcolonial and postimperial issues in Balkan culture.