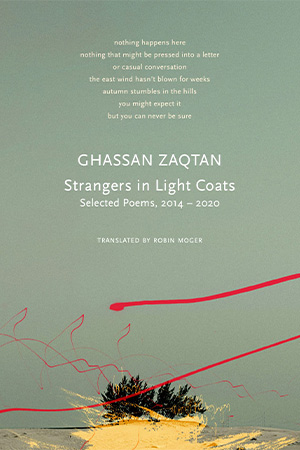

Strangers in Light Coats: Selected Poems, 2014–2020 by Ghassan Zaqtan

London. Seagull Books. 2023. 96 pages.

London. Seagull Books. 2023. 96 pages.

Palestinian American poet and translator Fady Joudah describes Ghassan Zaqtan as “a lyricist with strong narrative impulse.” Such is certainly the case in this anthology of poems originally published between 2014 and 2021 and translated by Robin Moger. The son of a poet, Zaqtan was born in Beit Jala near Bethlehem and held several editorial and political positions in Ramallah. The judges of the Griffin Poetry Prize, which he received in 2013 for his collection Like a Straw Bird It Follows Me, translated by Joudah, praised his poetry for “awaken[ing] the spirits buried deep in the garden, in our hearts, in the past, present, and future.”

In Strangers in Light Coats, Zaqtan invokes a multiconfessional Palestine through the figure of Sarah, Abraham’s wife and Isaac’s mother, who becomes a fluctuating and itinerant interlocutor as the poet voices his people’s torments: “I have no home and you have no exile.” The collection is imbued with an obsessive sense of place and movement. Palestinians, Zaqtan reminds us, are forced into displacement, “born to go, / the going that does not see, / the going that does not stop.” The recurrent Palestinian theme of exile is embodied in displaced individuals “passing through the shadows with no urge to arrive” and “wretched ramblers” whose faces “trigger doubts.” The Palestinian experience encompasses a haunting absence, shaped by the tragic loss of both land and people.

Zaqtan’s acute attention to mountains, trees, woods, rocks, and rivers transforms landscapes into active poetic subjects: “River, river, / take our people north, / help them through the hunger, cold, and wind, / take the pictures of the dead and take their bread.” While nature is constantly traversed and reconfigured, people are often left without guides, taking paths that lead nowhere or never reaching their destination. Poetry often faces blindness, grappling with undecipherable images and unsettling sounds. Navigating alienation, Zaqtan’s poems vividly capture the pain and angst experienced by Palestinians as well as their “frail hopes and glorious defeats.” Listening to stories of survival and return, the poet is often left alone to document the transformation of spaces and memories.

As in other Palestinian poetry, Zaqtan’s writing reveals a unique tension between memory and violence. Poetry celebrates “the power of premonition,” capturing fleeting signals and metaphors, pausing on images that never happened or that no one remembers. In the poems, troops come and go, while soldiers’ ghosts and relatives reappear: “the war eats those who kill and those who are killed / and nothing comes home but the howl.” Yet it is the unmistakable traces of this endured violence that enable the poet to recognize his land. The poem “When that happens,” for instance, is a lengthy litany of all the signs, people, and landscapes that define the homeland.

From one poem to the next, time often loops, vanishes, and deceives the poet’s memory. Months and seasons seem increasingly unpredictable, and a deep anxiety pervades several poems. When the poet evokes sleeplessness, it is the ongoing ordeal of Gazans that comes to mind: “I wake because of the dogs that bark in my memories, / I wake because of the war, / because of the fear that crawls behind the sandbags, / and peers from the cracks.” Even the poet’s dreams are filled with lost friends. The only respite is “undressing the silence,” seeking a way to connect with the unseen.

Although political resistance is somewhat subdued in Zaqtan’s poetry, his writing grows more assertive when engaging with individual and collective identity. In “Drowned, they remember the horses,” he reflects on the decline of Arabs and their attachment to vestiges and ancient myths: “Here they are, the eloquent Arabs, falling / from the books of rhetoric, the marvels of the grammarians / from expression’s expanse and cramped meaning, with their blood / admixed by raiding, its purity surrendered to defeated nations.” The poem reads as a scathing critique of the burdens of the past and its dogmas in Arab culture, while also highlighting the devastating effects of cultural dispossession: “their marvels and manuscripts and silent statues / in the cold museums of the north / shed tears.”

Zaqtan’s more personal poems explore themes of (re)birth and origins: “I was born into the Christian households of Beit Jala, / the spacious stone homes / over the olive presses.” The poet’s inward turn often prompts him to identify with others and reflect on the reception of his work and his position in society: “I write things my friends don’t like, / footnotes that my neighbors, robbed by life / each passing day, skip by, / muffled texts that my companions in the café quite ignore, / poems no one loves, / preoccupied with absence and with loss.”

Open to the world, Zaqtan’s poetry frequently references various countries and regions, including Oman, Syria, Jordan, Greece, as well as the Moroccan Rif and Kurdish villages. Eminent figures such as Said, García Lorca, García Márquez, and Kawabata also appear, but the most significant influence is Constantin Cavafy, particularly his 1904 poem “Waiting for the Barbarians,” which resonates throughout the collection.

Beyond recurring motifs, figures, and dialogues that create a consistent narrative thread, Zaqtan’s poetry embodies a unifying and deeply Palestinian sense of resilience: “At night, while they sleep, / I write blind poems / and hold their hands / and we push on in the dark.”

Khalid Lyamlahy

University of Chicago