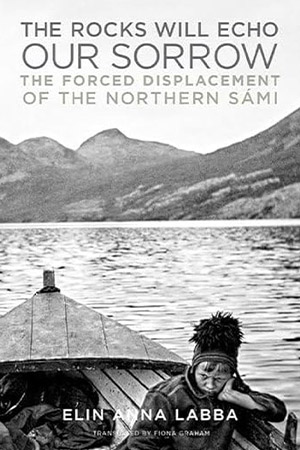

The Rocks Will Echo Our Sorrow: The Forced Displacement of the Northern Sámi by Elin Anna Labba

Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press. 2024. 197 pages.

Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press. 2024. 197 pages.

History grows on solid, settled ground. Migration, relocation, and displacement leave transitory imprints but virtually no documentary traces; and if they do, their claims tend to be muffled in the silence of the archives. In recent times, the partition of colonial empires and the creation of modern nation-states resulted in the forced relocation of communities, groups, or entire populations on virtually all continents. Of these, nomadic pastoralists have been and continue to be the “stereotypical” victims of nation-building, land partitions, and their consequent border enforcement policies and practices. Their patterns of migration and their overall lifestyle are fundamentally incompatible with settler economies (i.e., agriculture, commerce, and industry), on which modern countries and their underlying (and delusive) ideology of progress and economic growth are founded.

Some relocations are more tragic, prolonged, and involve larger groups than others, and because of these (and other reasons) they are better documented or receive more popular and media attention. (The Trail of Tears and other forced displacements of Native American groups are a case in point.) Others are less known or largely unknown outside small scholarly enclaves. This is the case of the Sámi reindeer herders, whose forced relocation from Norway’s northern seaboard in the early decades of the twentieth century is brought to life by this eye-opening and engaging book.

“Boundaries have always existed,” explains Elin Anna Labba—a Sámi journalist whose family was among those affected by relocation—“but they used to follow the edges of marshes, valleys, forests, and mountain ranges. The new borders of the Nordic nations cut across all natural systems. They cut through pastureland, family ties, and transhumance routes that have been in use for thousands of years.” The process started in 1751, with the establishment of the border between Norway/Denmark and Sweden/Finland but gathered momentum after Norway became an independent nation in 1905, when land became increasingly a commodity and reindeer herders “an anachronism in the new Norwegian nation.” The leader of the Labor Party at the time could not have been more explicit in declaring that “the nomadic way of life places a burden on the country and the settled population, and is hardly in keeping with the interests and the order of civilized society.”

Forced relocation started soon after Norway and Sweden signed the first reindeer grazing convention in 1919. The newly created Lapp Authority oversaw its enforcement, coercing compliance with all sorts of intimidation tactics, falsifying documents and statements, and resorting to the slaughter of reindeer when herders refused to leave or dragged their feet (or even when the animals, forced to travel south, would turn around and go back to their old pastures).

Following the relocation of a few families, and combining historical documents, photographs, and recorded interviews with her own personal and familial connection to the events described, the author does justice to her subject in a way that a scholarly work would not do. History gets personal, soft-spoken yet eloquent, as the rhythm of the events is offset by the melody of the joik, a form of Sámi vocal music that is “often addressed to features of the landscape, such as mountains, hills, or lakes, or to animals and people.” This finds a poetic equivalent in passages where the translator, Fiona Graham, shows her craft as well as empathy with her text: “the tussocks of scrub crackle with dryness, and the cloudberry flowers have closed.”

Graziano Krätli

North Haven, Connecticut