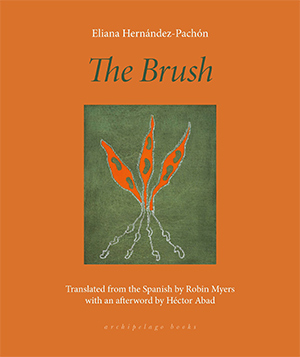

The Brush by Eliana Hernández-Pachón

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2024. 72 pages.

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2024. 72 pages.

The poetry of Eliana Hernández-Pachón’s The Brush explores the limits of language to communicate horror, centering on one of the worst massacres in twenty-first-century Colombia, that of the village of El Salado. The Spanish title of the work, El Bosque, translated to “The Brush,” can also mean “the woods” or “the thicket,” terms that capture the image of the wooded area where the executions took place.

The first two sections follow Pablo, a farmer, and Ester, his wife. Pablo senses impending disaster and gathers his valuables to bury in a metal box. He then disappears. In her section, Ester considers pulling weeds in the garden as she contemplates the woods, where “it’s never really daytime, why / is it so dark, she wonders.” As she returns to the brush, she experiences a rising sense of horror. Time passes and Pablo does not return from his walk to town. In the woods, she encounters a woman and her young daughter, witnesses unable to speak of what happened. All the mother can do is show the cut marks on her arms. Later, a young girl gives Ester the shirt she fished from a stream.

The final section, “The Brush,” is a collage of voices that include the witnesses, the investigators, and, finally, the brush itself, each providing snippets of testimony in a weaving, intercalated narrative. The juxtapositions of witness perception, investigator findings, the view from inside the woods, and, finally, unanswerable questions slowly paint a multidimensional representation of horror—one that is not achievable through a traditional linear narrative or in a poetic discourse reliant solely on figurative language.

Evoking the art and poetry of the Spanish Civil War, such as Federico García Lorca’s sounds of the bullfight with tragic death and Pablo Picasso’s cubist Guernica, the section both weaves and then unweaves itself, insisting on the ultimate unknowability of reality and the meanings of lived experience. All meaning is a construct, and one that unravels at the touch. The witnesses’ voices are emotional and experiential as they recount the cacophony of gunshots, blaring fiesta music, and torrential rain. In contrast, the investigators’ voices are clinical as their scientifically informed gathering of data and facts is guided by questions of motive. Finally, the brush is the physical place of intersectionality where perspectives show their limitations: the women who enter seeking their husbands have one set of knowledge, while the bodies that march in and finally are absorbed into the verdant oblivion have another. The women have knowledge of life and hope. The bodies have knowledge of the inescapability of death.

Knowledge of human motive is unknowable, and the only constants are the trees with interpenetrating limbs, the sun overhead, and the fragrant tangles of flowers: wild geranium, totumo, candelabra, bougainvillea—all “experts in disobedience”—and, finally, “the flower they call amor que zumba, / love abuzz — / abundant clusters, blooming from themselves.” Hernández Pachón’s The Brush ends in a depiction of life and love that persists despite human brutality.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma