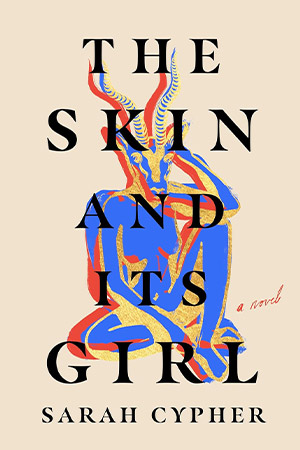

The Skin and Its Girl by Sarah Cypher

New York. Ballantine. 2023. 352 pages.

New York. Ballantine. 2023. 352 pages.

Born at dawn in a nondescript Portland hospital, Elspeth Noura “Betty” Rummani, the protagonist in Sarah Cypher’s debut novel, The Skin and Its Girl, is anything but ordinary. With an uncanny cobalt-blue hue, she is reminiscent of the blue soap manufactured by the centuries-old family business that gets obliterated the same day in an air strike on Nablus.

Years later, as an adult, Betty faces a difficult choice: staying back in America where her family has settled decades after immigrating from Palestine, or traveling abroad to start a new life with her girlfriend, once again embracing the outsider figure. Sitting by the grave of her overbearing aunt Nuha, she sifts through the emotional chaos of her childhood and attempts to piece together the old woman among the many tales, half-truths, and lies she told, hoping to find guidance in her story.

In Betty’s lyrical meditations on storytelling, one analogy particularly stands out: the English word “story” is the same as the term for the floors of a building, reflecting how stories layer thoughts into a palimpsestic “tower of ideas” filled with facts, fictions, and exaggerations. Her oral odyssey into the past unravels the narratives of three generations of Rummani women—Aunt Nuha, Grandmother Saeeda, and Mother Natasha.

Yet, interwoven between Saeeda’s sale of the soap factory, Tashi’s hearing her dead father’s voice, and Nuha’s choosing of family over love are many other stories. These include Betty’s experiences of being bullied at school due to her unassimilable identity, her father’s excavation of cannonballs, Nuha and Saeeda’s troubled trip to Palestine, the numerous fables of Babel, the silver gazelle, and the boy whose hair was fire. As the novel jumps across time—from the 1800s to British Mandate Palestine, the Nakba, the Second Intifada, and 9/11—Betty draws courage from the fears and regrets of the seemingly normal yet equally unfixable Rummani women, who are fated to be unlucky in love, to pursue her own chance at happiness.

Cypher’s use of magical realism to fuel Betty’s quest of untangling family lore to make sense of herself as a queer Palestinian American, blue as the Mediterranean but also the Star of David, offers a powerful way for diasporic Palestinians to reimagine their ties to the conflict-ridden homeland in the face of stark statistics and the finality of no return.

Sreeparna Das

University of Cincinnati