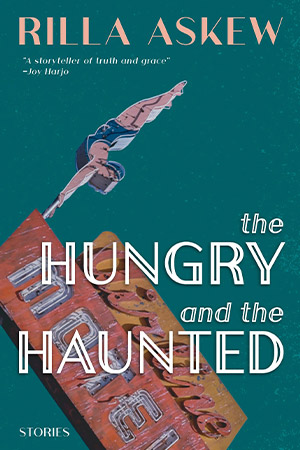

The Hungry and the Haunted by Rilla Askew

Fort Smith, Arkansas. Belle Point Press. 2024. 160 pages.

Fort Smith, Arkansas. Belle Point Press. 2024. 160 pages.

It’s been thirty-two years, five novels, and an essay collection since Rilla Askew published Strange Business, her debut short-story collection. The Hungry and the Haunted evinces a mastery of characterization and plot development through years of practice in the novel.

Of the six in the collection, three interrelated stories are gathered into a section entitled Tahlequah Triptych. Tahlequah is small town in northeastern Oklahoma and the capital of the Cherokee Nation—Askew’s stories reflect a deep knowledge of Tahlequah’s landscape, its history, its culture, and its people. The Cherokee Trail of Tears amphitheater and its musical theater reenactment of Cherokee Removal is present in all three stories, a site of triumph and failure, survival and sorrow, the travails of the hungry and the haunted.

The first story of the triptych, “The Color of Verdigris,” is told from the perspective of Reva, a teenager. Four years before the story opens, her father left the army and her mother in California, then moved the two of them to his hometown, Tahlequah. He bought a “tatty hotel,” where they live in an apartment behind the office. Throughout the story, her father remains inscrutable, both to Reva and to the reader.

On her first day of junior high, Reva “found she was invisible.” On her seventeenth birthday, she bleaches her hair white-blond and is suddenly visible—boys whisper “sexy, dirty things” to her and the girls say she “looks like a skag!” It’s enough for Reva at the moment that they can see her, no matter how they see her. The day after graduation, she moves “into a rundown house,” never returning to her father’s apartment, still hungry to be seen.

The second story, “Hunger,” focuses on Nikki, a refugee from California. After a series of bad choices that left Nikki emaciated from living in a drug flophouse, her mother banishes her to Oklahoma to live with relatives. Nikki soon escapes to Tahlequah, where she meets Floyd Sixkiller, a Native ballet dancer, in a bar. For much of the story, Floyd’s companionship allows Nikki to embrace her dreams and desires. She realizes that “She wanted . . . beauty. To look at it. To breathe it.” Later in the story, Nikki asks Floyd to name the impossible-to-obtain secret of his heart. Floyd wants to “fly like I do in my dreams.” Nikki, in extension of her wish for beauty, wants to be an artist, but her tentative attempts to paint and draw seem to her proof that the dream is impossible. When she moves out of the home she shares with Floyd and his roommates, she becomes unmoored.

The third story of the triptych, “That Grief, That Rage,” is narrated by Floyd’s mother, Juanita, who was adopted by non-Native people who lived in Tahlequah. Juanita does not know if her adoption was forced, as were many of the era, or if her parents gave her away. She is haunted by the desire to know who her real parents are, what tribal nation she belongs to, and, therefore, to learn who she is.

“Solstice,” “Two of Her,” and “Ritual” round out the collection. “Solstice” centers on a pilgrimage taken by a girl and her great-uncle who is searching for forgiveness and redemption. “Two of Her” introduces Elaine, a steady young woman who takes care of her mother. Elaine knows that she has a real self that “she turned to the world” and her dream self, “who she was—who she would be” if she could escape her small town. “Ritual” opens with the yearly journey of Aradhna, the main character, to the Woodstock festival site where she honors the life of her deceased best friend. Aradhna finds purpose and a direction for her life through a chance meeting with two others on a far more dangerous journey.

Askew’s characters are aware of their faults and struggle to overcome them, sometimes failing at the task. Female characters are exceptionally well drawn—complex and true to their age and experience. Floyd Sixkiller is compellingly rendered, and one wishes for a collection of Sixkiller stories. Tender, harsh, loving, devastating—the emotional impact of the collection lingers long after closing the cover. The Hungry and the Haunted is a brilliant collection that earns a second or third reading and a space on everyone’s shelf.

Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

Albuquerque, New Mexico