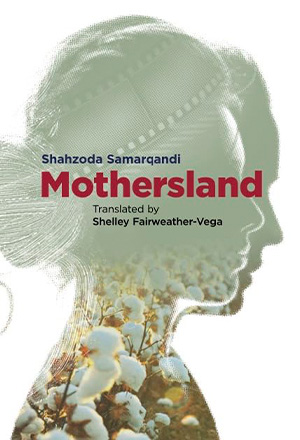

Mothersland by Shahzoda Samarqandi

Bloomington, Indiana. Slavica. 2024. 71 pages.

Bloomington, Indiana. Slavica. 2024. 71 pages.

From the late nineteenth century onward, cotton became Central Asia’s predominant cash crop. To sustain the fields and fields of this “white gold” across the region’s arid steppe in the Soviet period, massive irrigation projects diverted river water from the Aral Sea, draining it in a matter of decades. Today, what remains of the once-vast Aral Sea is a smattering of salt-thick pools.

Published in Tajik Persian in 2013, and newly translated into English by Shelley Fairweather-Vega (via Yultan Sadykova’s 2019 Russian translation), Uzbek writer Shahzoda Samarqandi’s novella Mothersland explores this human-engineered climate catastrophe from the perspective of a young Uzbek woman, Mahtab.

Following an unspecified accident, Mahtab has lost her memory. Throughout the novella, she tries to make up for the blank spaces in her mind by immersing herself in her mother Aftab’s old diary entries (while Mahtab means “moonlight” in Persian, Aftab is “sunshine”). As a young woman, Aftab lived on a cotton-producing collective farm (a kolkhoz) in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. An intensely ambitious, “manlike” woman, Aftab ended up rising to the position of deputy chairperson of the farm, donning pants and maneuvering the farm’s sole red tractor across the cotton fields. For Aftab, cotton was a “paragon of truth,” a seemingly immutable feature of life on the steppe that would not falter through changing political regimes. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Aftab’s red tractor breaks down for good, lying in disrepair as the fields of the former kolkhoz are consumed by housing developments.

In this disorienting landscape of post-Soviet, capitalist Uzbekistan, Mahtab lacks the clear-cut ideology or sense of purpose that cotton farming had afforded her mother. What Mahtab does have is the leading role on the cast of a Russian-made movie–one that re-creates a utopian, nostalgic version of her mother’s life as the archetypal Soviet “woman hero.” With no firm sense of her own, genuine voice, Mahtab eagerly takes on the persona of her mother as a young woman, allowing herself to be sucked into “the closed loop of the distant past.”

The narrative, untethered from chronological time and strict character boundaries, floats between Mahtab’s confused thoughts and Aftab’s diary entries, without always distinguishing between the two. As Mahtab’s memories fuse with and drift away from those of her mother, time slides forward and tips back. The storyline follows a subconscious, somnambulant sort of logic in which time occasionally “shudders, then disappears.” Mother and daughter’s stories merge together “as if they were made of raw dough,” then “set themselves free again.”

In Fairweather-Vega’s translation, Mothersland is a plush and chimerical dreamscape. A city might be “seething green” or covered in snowflakes that pour down in “a cold, white riot.” Parceled out in fragments, the language is velveteen and light, buoyant with synonyms. Mahtab compresses a cotton ball, watching it spring back into shape, “like touching a breast, soft and gentle.” But turn the page, and this chiffony, dreamworld-like sensibility might morph into something macabre. Images occasionally loom up from the fog of Mahtab’s memory with horrifying clarity. A girl sits in a padded hospital room, staring up at the surveillance camera that watches her. The lone red tractor on the kolkhoz stands tall in the cotton field like a “holy phantom”—ominous and ghastly. Bones sometimes crunch under the tractor wheels.

One such shadow is the relationship that Mahtab has with the Russian film director, Mikhail. “When I start looking for someone to blame,” Mahtab reflects, long after the film was shot, “I always remember the director.” While it is unclear exactly what transpired between Mikhail and Mahtab (“mutual sympathy or mutual torture, I don’t know”), their character pair can be seen to stand in for the complexities of the historical power imbalance between the USSR/Russia and Central Asia. Mikhail extracts a raw performance from Mahtab much in the same way that the Soviet (and later, Russian) material economy has relied upon Central Asian cotton yields as a resource to process in textile factories in the metropole. “What exactly did he find so attractive about this field?” Mahtab wonders about Mikhail’s oddly passionate fixation on cotton farming. “Why cotton?”

But Mothersland rests on enigma, and many such questions go unanswered. Instead of realist explanation, the narrative tends to describe Mahtab’s world through metaphor. For example, the near-disappearance of the Aral Sea due to aggressive Soviet irrigation practices is, in Samarqandi’s prose, evidence of a failure of love: “The Aral Sea has a broken heart, and in the face of everyone’s indifference, it’s taken its own life.”

Samarqandi (b. 1975), a young Tajik feminist writer, is known not only for her novels and poetry but also for her journalism, reporting in recent years on how Taliban rule has affected Afghan women. These disparate strains of her writing life—a poetic sensibility combined with a desire to expose injustices—are on full display in Mothersland. By setting the loss of the Aral Sea as the backdrop for a story of one woman’s relationship to her mother, Samarqandi has written a novella that is at once politically and emotionally resonant.

Anna Learn

University of Washington, Seattle