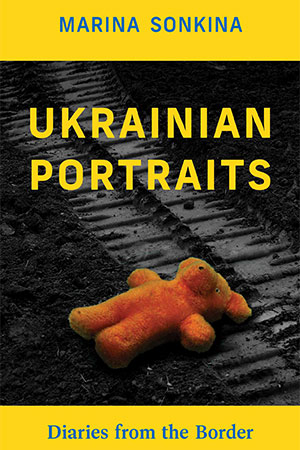

Ukrainian Portraits: Diaries from the Border by Marina Sonkina

Toronto. Guernica Editions. 2023. 121 pages.

Toronto. Guernica Editions. 2023. 121 pages.

Marina Sonkina’s Ukrainian Portraits: Diaries from the Border follows the Russo-Ukrainian War’s initial days, when thousands of refugees poured through Ukraine’s borders into Poland and other European and North American countries. The portraits of Ukrainian refugees that Sonkina paints are respectful, heart-wrenching, and inspiring. Sonkina compellingly captures a unique call to action—not only for Ukrainians, their nation, and that nation’s sovereignty but for humanity as a whole.

The book opens with Sonkina’s own reflection about leaving Vancouver and arriving at the Polish–Ukrainian border at the Korczowa refugee center in order to volunteer. As Sonkina embarks on her unique journey, she encounters grotesque stories of “booby-trapped corpses, of Russians abandoning their dead.” However, she candidly acknowledges that the most heart-wrenching stories were women’s stories. She “discovered that the most painful subject that came up in conversations was the fact that women had had to leave their loved ones behind.” Thus, for Sonkina, these stories present the war in such a context that when “a collective image of Ukraine comes . . . to mind, it’s women’s eyes.”

Sonkina’s sentiments resound with a profoundly shocking statistic. According to UN Women, as of February 2023 around “60 percent of the 7.7 million internally displaced adults are women while 90 percent of the 5.6 million refugees who fled Ukraine are women and children.” Thus, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made the displacement experienced one of the “most gendered displacement crises” in current times. Despite that frightening statistic, as well as the harrowing tales of escape shared by the refugees with Sonkina, the book does not always focus on the war’s violence and brutality.

“Tikkun Olam” shares an awareness about a simple concept that the war’s brute force could have easily overshowed: kindness. “Putin’s war unleashed death and destruction,” Sonkina writes, “but inadvertently, it has also set free the generosity and kindness that easily stay dormant locked inside the shell of our routine lives.” This particular excerpt in Sonkina’s book gives readers insight into the Polish people’s generosity, and the title refers to the Jewish tenet of tikkun olam, “the moral responsibility to repair the world and alleviate suffering wherever it exists.” Sonkina highlights how organizations like the Jewish Distribution Committee worked tirelessly to help Jews and non-Jews alike, provide for their needs, and reach safety.

Uniquely, Sonkina focuses on Russians—“inside and outside of Russia”—who helped Ukrainians despite the danger and illegality of doing so. Sonkina briefly discusses a “clandestine network” in Moscow and St. Petersburg that assisted “Ukrainians deported to Russia in reaching Western Europe.” Russian émigrés living in Slovakia organized humanitarian efforts for Ukrainian refugees and simultaneously “found themselves in crosshairs” because “the sight of their red passport with a crowned eagle caused suspicion in the eyes of the Slovaks.” Sonkina’s portrayal of the clandestine network mirror those depictions of the World War II underground groups that helped Jews escape war-torn Europe.

In “I Saw Their Faces: Oleg, Oksana, Jaroslav,” Sonkina covers the diverse journeys of three Ukrainian refugees. The brief essay opens with Sonkina’s amazement that despite the war, “a smaller, but substantial countercurrent was going in the opposite direction, back home, to Ukraine.” She makes the acquaintance of Oleg—a women’s shoe designer, his wife, their baby, and their older daughter. Oleg’s story is a distinctive one in Sonkina’s book. Unlike many of the Ukrainians Sonkina helps, Oleg does not plan to return to Ukraine. Upset with Ukraine’s politics and the country’s direction under Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Oleg determines that he and his family will venture to Denmark.

Later, readers meet young Yaroslav, a fifteen-year-old determined to help and protect his mother, Oksana. Sonkina uses Yaroslav and Oksana’s story to give readers a journey through Kharkiv’s World War II history: “It’s as strategically important for Putin as it was for Nazi Germany eighty years ago” even though the Russian army liberated Kharkiv at the high expense of “three battles and half a million soldiers’ lives later.” The placement of Sonkina’s historical context is important, because it allows readers to see the parallels between significant events in Ukraine’s history and the brutal events unfolding in Ukraine today under Russian occupation.

A concise collection of 121 pages, the emotional power of Sonkina’s collection partially derives from its brevity. That brevity also mirrors the swiftness of Sonkina’s experiences as well as the rapidity with which the war’s early days passed as the globe held its breath and watched Europe’s largest ground war since World War II extend across a country literally dying for its freedom. Sonkina’s astute prose draws attention to those the masses and the world would most likely forget, and it reminds readers about the importance of—and necessity of—lending a helping hand, an open room, or a plate of hot food to those in need.

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University