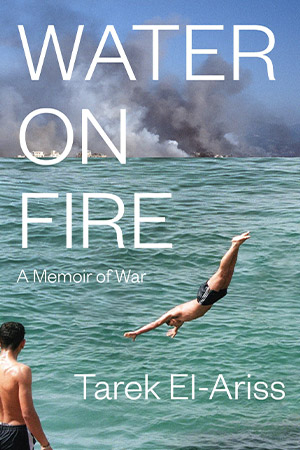

Water on Fire: A Memoir of War by Tarek El-Ariss

New York. Other Press. 2024. 272 pages.

New York. Other Press. 2024. 272 pages.

In his first autobiographical work, Water on Fire, Tarek El-Ariss invites us into his world at a moment of profound personal crisis. After years immersed in the rigorous study of literature and psychoanalysis in upstate New York, El-Ariss finds himself teetering on the edge of burnout. The sudden collapse of his carefully constructed intellectual world prompts him to self-diagnose, to search for some grand, elusive reason behind his physical and emotional unraveling. He shows up at a recommended psychoanalyst’s office with “family pictures in one hand and teenage poetry in the other” in search of nothing more than a second opinion, a confirmation of a diagnosis he’d already determined; “a happy family with a bit too much affection, perhaps.” He admits, “[s]he needed to see it so she could fix me, put me back together, and erect that boundary that should have been there from the beginning.”

Yet, as he seeks in his earnest erudition the help of a professional—the solution to his problem of proximity—her response is disarmingly simple: “I thought you were from Beirut. Don’t you want to talk about the war?” This question shifts the narrative focus from the anticipated psychoanalytic exploration to the long-buried trauma of conflict. It’s in this instance that we begin to understand that the war is the wound, and the scars run deeper than his academic pursuits have allowed him to acknowledge. As the memoir unfolds, it becomes evident how in other respects El-Ariss uses intellectual pursuits as a refuge from the spontaneous violence and severed familial ties synonymous with the world around him.

Recounting the years of conflict in Beirut, much of which surrounded its resources and water, Tarik digresses into an exposition of water’s “divine origin and miraculous properties”; about the alternative use of the unit measurement gallon to describe the plastic water containers during the civil war that circulated through Beirut in different shapes and colors. He recalls how his family was forced underground for the first time following an explosion that sent his brother flying to the other end of his room and his father screaming across the rubble that was once his home to consolidate his family (all of whom are miraculously unharmed). He observingly describes this as the age of Aquarius, when “city dwellers [were forced] to dig wells, buy water, and store it in parking lots and makeshift tanks in their homes.” We are reminded in all of it that “Beirut” in ancient Semitic languages, Beeroth (Berytus in Latin), means “well.” And that citizens adjusted to this city on fire were equally accustomed to swimming in the sea at the height of the conflict, despite the risk of bomb and artillery fragments that tragically, one afternoon, pierced the flesh of a schoolmate. Suddenly, El-Ariss felt the Lebanese were turned inland, made to tunnel for the waters underneath. But one can’t help but notice the refrain of his intellectual escape, his tendency to drift away from painful moments by etymologizing and layering them in history, in narrative. “Did I mention,” he writes, “that ‘cutting’ and ‘storytelling’ are the same word in Arabic?”

But lurking in the cutting is the issue of identity as well as, although less admittedly so, the cognitive dissonance instigated by his expatriation to the United States. El-Ariss reflects on his half-siblings and his father’s marriage to his first wife, an American woman he meets during his medical studies abroad. His decision to repatriate to Lebanon with his American wife may very well be seen as a political one, but underneath it is the insinuation of something spiritual—an inseparable relationship to the land that compels him to stay even as it becomes unlivable. Following the summer of 1982, when Israel invaded Lebanon with the stated objective of kicking out Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and his fighters, El-Ariss mentions how his father’s marriage to his first wife ended in an acrimonious divorce where, one imagines, the patriarchal ruling at the time granted custody over his children to his father. The result of this severance will play out in the marriage to his second wife, Tarek’s mother (a Lebanese woman), whose bright blue eyes she passes on as a distinctive feature to her first and only son. A scene that replays the exquisite sensation of loss—as little Tarek tries to squeeze himself in the suitcases of his brothers and sisters who are leaving to be reunited with their mother—reoccurs as El-Ariss, now too grown to conceive of making himself small, must watch as his mother leaves for the United States as well, following his father’s passing—abandoning him to live with relatives in Côte d’Ivoire.

El-Ariss’s memories of Côte d’Ivoire are fond ones, but the idea of America as a place of reunion and respite has long been planted. Although the United States’ contribution to the instability in the Middle East could not have been lost on him, he nonetheless skirts over it, hovering instead on the Islamophobia following 9/11 and his shared sense of dislocation during the Covid pandemic. But, as any immigrant would observe, these coping strategies are intrinsic to one’s physical and psychological survival. “It wasn’t just the violent attacks, the devastation downtown, or the dead and the missing,” he writes, “but that suddenly we all had to explain how we fit into a simple algorithm of identity. . . . I realized that no country or city or job could ever provide me with the security I craved. No matter my status and position or the passport I hold, the quest for a shelter had become completely futile.”

Lethokuhle Msimang

Dartmouth College