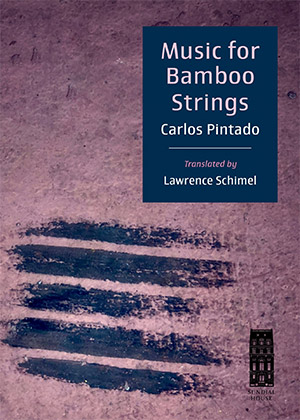

Music for Bamboo Strings by Carlos Pintado

New York. Sundial House. 2024. 152 pages.

New York. Sundial House. 2024. 152 pages.

Aptly titled Music for Bamboo Strings, there is a melodic quality in this collection by Cuban American poet Carlos Pintado. Recipient of the Sundial Literary Translation Award, Music for Bamboo Strings has been exquisitely translated by Lawrence Schimel. In addition to the Sundial Award, Pintado was the recipient of the 2014 Paz Prize for Poetry for his collection Nine Coins / Nueve monedas (2015), translated by Hilary Vaughn Dobel.

Structurally, the collection contains sixty-two poems and a preface by fellow Cuban American poet, translator, and novelist Achy Obejas. Obejas begins her preface, “When I received Music for Bamboo Strings, I ate it up. I swallowed it whole and scraped at the pages, wanting more.” While this kind of paratext is often prone to excess or gratuitous flattery, Obejas is not exaggerating here. These poems do leave the reader, if not wanting more, then eager to read and reread the poems before them.

The collection begins with the poem “In Praise of Shadows,” a paean to Junichiro Tanizaki’s essay on aesthetics of the same name. “A few times per year my fingers brush the pages of In Praise of Shadows. Junichiro Tanizaki won’t know that I’ve read it so often that it’s enough for my fingers to whisper over the pages for the words to resound like the unmistakable echo of the bells of a Kyoto temple.” Shadows remain—as does Japan—a recurring motif in the poems that follow. And while music is omnipresent—in bells, in birdsong, in cawing crows, in whispers, in the rustle of leaves, in the wind—it is also present in the slow and measured cadence and rhythm of meticulously crafted lines, in the original and in the translation.

The second poem, “The Swimmer, Cheever, Another Story,” was familiar to me, as I had translated it seven years ago for publication in Latin American Literature Today. I must say, with absolute frankness, that I like Schimel’s translation more than my own, in the subtle choices he’s made where poetry resides. Where I wrote, “I’ve loved like only a man getting on in years should love: fearfully, cautiously, almost to the point of exhaustion,” Schimel is more restrained: “I’ve loved as only a man of advancing years must love: with fear, with precaution, with exhaustion,” avoiding the glaring grammaticality of the adverbs “fearfully, cautiously,” in favor of the quiet anaphora of “with fear, with precaution, with exhaustion.”

In the most generic sense, these are prose poems, but beyond this formal classification, we find lyrical poems, ekphrastic poems, odes, elegies, ballads. At times a poem is all of these. Consider “The Greek Vase,” which reads: “They fought on the vase an impossible war: the vase had resisted years of horror, or blows. He remained, naked, above his adversary; the adversary, perhaps too young, also showed a certain nudity.” Is this an ode, an elegy, an ekphrasis? Yes, yes, and yes.

The corporeal is front and center in these poems. In “Field of Wheat,” we read, “That I might say: this is your hand, your tongue, your body. Let everything be simple, like tossing a stone into a lake.” There is much of Whitman in this and other poems in the collection. And, like Whitman, Pintado sings the male body unabashedly. There, too, is much of Lorca’s Poet in New York in poems such as “Landscape on a Postcard,” which reads, “I could stretch out my hand and touch the object, the pure flesh, sleeping beside my body.”

Many of the poems carry dedications. Some of the dedicatees the reader might know, such as Cuban singer Gema Corredera; others bear only a first name. Who is Manuel, to whom Pintado would dedicate such suggestive lines as “My eyes already know Marmara’s moon, the Sultan Ahmend Mosque, and the young man in the Istanbul Bazar”? Or Adrián, refracted in the lines “We held death in our eyes, in our lips”?

Born in 1974 in Pinar del Río, Cuba, Pintado is heir to a long and distinguished line of Cuban poets—Virgilio Piñera, José Lezama Lima, and Reinaldo Arenas—all of whom lived in exile, whether internal or external, victims of a regime that demanded fealty to ideology over art. Pintado is equally at home in verse and prose. (If you have a moment, treat yourself to his short story “Snow” in the May 2016 issue of WLT.)

It is not (co)incidental that Pintado would write—compose is a more fitting verb—a collection of poems that feature music as an organizing motif, as many of his poems have served as the basis for musical compositions, including Tropical Rhymes, whose music was composed by the Pulitzer Prize–winning Cuban American composer Tania León, who also composed music for his cycle In the Field, which was performed recently at the Tanglewood Festival for Contemporary Music.

I can think of no one more suited to compose the English translation of Music for Bamboo Strings than Lawrence Schimel. In this text, he brings all his literary force—as translator, author, poet, and publisher—to bear. My only objection is that the original poems and translations do not appear on facing pages, realizing, of course, that this may have been an editorial decision rather than a creative one. That cavil aside, Pintado and Schimel form an extraordinary team, which makes news of a new collaboration, HaiCuba/HaiKuba (forthcoming from NorthSouth Books), a children’s book of haikus about Cuba, all the more exciting.

Music for Bamboo Strings begins with an epigraph from the late French poet Yves Bonnefoy: “Will words betray us?” I am happy to say that the words composed by Pintado and Schimel have not.

George Henson

Middlebury Institute of International Studies