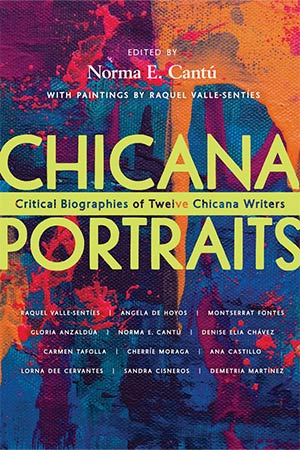

Chicana Portraits: Critical Biographies of Twelve Chicana Writers

Tucson. University of Arizona Press. 2023. 362 pages.

Tucson. University of Arizona Press. 2023. 362 pages.

Chicana Portraits is a powerful examination of the impetus and pilots behind the phenomenon of Chicana literature. Today it is well known there are Chicana and Latina writers, but such a category only began a little over a generation ago. In the 1980s a handful of Mexicana and Chicana novelists surprised and fascinated readers; academics moved to publish books with interviews and translated excerpts from Mexican women writers. Simultaneously, Chicanas were churning out works and shepherding new writers.

As more and more US Chicanas achieved publication, critical texts discussed the writers singly or for their themes and techniques. But what were their influences? Chicana Portraits answers that question, discussing twelve important early writers, born in the 1940s and ’50s, literary coaches and activist mothers whose deep involvement in community influenced new writers. Their own writing continuous since the 1970s, they helped bring forth new generations of writers. An earliest, significant influence was Angela de Hoyos, who engaged with the greater Spanish-speaking world and jazz movement in the 1960s and ’70s: an influential poet, teacher, editor, and publisher, she opened the road to Chicana/o recognition. Lorna Dee Cervantes brought Mexico, El Salvador, and the US into activist sociopolitical consciousness and created new publishing venues in the 1980s and ’90s (see WLT, July 2010, 28).

During the 1980s, Demetria Martínez opened minds to refugees and to the violence that marks bodies while society steps over them; Gloria Anzaldúa defined experience and sexualities through geopolitical and transnational ruptures to bodies and borders. Working within and for the community, Carmen Tafolla created portraits in her poetry of both rural and everyday characters in San Antonio neighborhoods, “through humor, humility, pain, and utterance,” as models and champions of hope.

Breakout creative writers Sandra Cisneros and Ana Castillo punctured the glass ceiling, while Denise Chávez drew audiences to her social commentary with theatrical magic. Equally theater-talented Cherríe Moraga weaved ancient heritage and social activism through inventive drama and endured negative reactions so that younger women could see themselves. Monserrat Fontes is remembered by numerous high school students as an important guide, but she also created cutting-edge works. Norma Cantú is described as a visionary, coach, guide, professor at four universities, and important founder and motivator of innovative spaces for newer writers, while publishing critical studies and bioethnographic novels.

The chapters in Chicana Portraits are framed by full-color images from portraits of each subject by Raquel Valle-Sentíes, a historic rendering of her observations and community base in Laredo from the early years through the creative 1990s. At 350-plus pages, there was likely little room left in Chicana Portraits for additional mothers of the Chicana writer movement like Helena María Viramontes and Lucha Corpi. A second volume is needed.

Elizabeth Coonrod Martínez

Austin, Texas