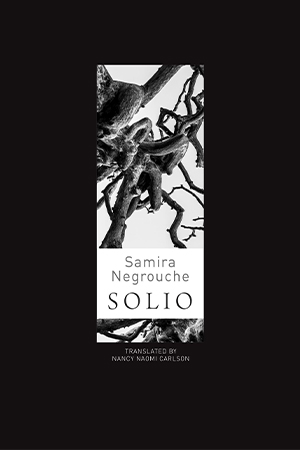

Solio by Samira Negrouche

London. Seagull Books. 2024. 140 pages.

London. Seagull Books. 2024. 140 pages.

Samira Negrouche (b. 1980, Algiers) likes mathematics and art. Science balances the infinitesimal and the cosmos; it organizes, labels, and counts, and it straddles abstraction and detail. Both are suited to describing the poet’s processing of a complex reality that reads itself through her. Order, balance, tension, and dynamics dominate the poems’ organization, whereas art dominates the poems’ content.

“Quay 2/1,” published in 2019 and the first section featured in Solio, is composed of three “axes” numbered I, II, and 2/1. Each “axis” contains untitled poems that echo the poet’s pre-encounter, encounter, and postencounter with the Other and that flow like uninterrupted variations on a single melody, perhaps because “Quay 2/1” was first written in collaboration with a musician and choreographer. “Traces,” published in 2021 and the second section featured in Solio, gives its poems numbers for titles and orders the world’s chaos on the pattern of sleep and wakefulness, echoing the primeval emergence of night and day.

This dual approach is all about the ways in which Negrouche lives poetry and about her own geopoetical experience of her surroundings. Solio—aptly named for a word whose root belongs to several world languages—means crossing, threshold, or coming to attention. This word, used in the last poem of the volume, showcases Negrouche’s repeated segue between presence and absence, observation and vision. It indicates her ability to shoulder the weight of the universe’s memory that lives in her “three mother tongues,” among which are Arabic and French, and in her Algerian and postcolonial French heritage, as noted in an essay she published in the March 2018 issue of World Literature Today. Her heightened sense of the perpetual motion set by human migration is a major theme of her work and provides her with rootedness.

Negrouche’s voyages are altogether familiar and unsettling, iconoclastic and ordered. Her language is minimalist to better make her exploration and discovery immediately palpable. The air “that sails the sky” and the wind that “sculpts eyelids” unmoor her from space-time limits while she travels from Mexico City to Ougadougou to Aden on the “oily surface” of the sea. She notes a friend’s story told in Auvergne about his mother, a Hungarian teacher of Spanish. She evokes the manifold meaning and uses of the “tongue” through its memory of taste. She describes a town invaded by the sea like a woman submitting to her lover. Her poetry reads like an unhurried act of poetic self-accomplishment. In her melodic chant, she tells of all things, beings, and encounters as traversing/being traversed, possessing/being possessed in the full bloom of agony and ecstasy: “I’ve been gifted / to live / what / in the white dawn / awakens.”

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin