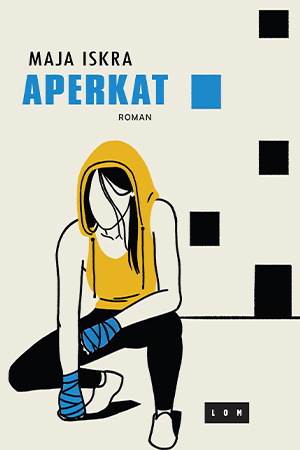

Aperkat: roman by Maja Iskra

Belgrade. LOM. 2023. 159 pages.

Belgrade. LOM. 2023. 159 pages.

Brutal, ruthless, cruel—this is life in the Belgrade neighborhood of Dorćol that Serbian writer Maja Iskra recounts in Aperkat (Uppercut), her critically acclaimed debut novel. She writes poignantly in a terse, almost telegraphic style, and the loose structure of the novel is built on a whirl of interconnected flashbacks. The protagonist, born in 1981, eventually moves to Vienna but maintains broad and deep connections to her home city and, importantly, her home neighborhood. The narrative is built on vignettes from throughout the 1990s as well as 2004 and 2013. And it unfolds to a rapid drumbeat of pop culture and literary references, from Dostoyevsky and Bataille to Jeff Buckley and David Bowie, from Wim Wenders and Gary Oldman to comic books and Tetris.

We briefly meet plenty of friends and lovers, and we encounter unusual teen hangouts such as an old cement factory and power plant. The narrator characterizes her emotional and intellectual development as “changing the idea of home,” a necessary yet very difficult task for even a resourceful and driven young woman. As a good friend notes, one of their shared legacies of childhood is “a perpetual brutality towards the people [we] love. The people who love [us] . . . That’s the heritage of our fathers.” Some of the most moving scenes recount harsh bullying in cafés, on street corners, and in school, including the bullying of a teacher—to which the narrator is usually a witness, not a participant. This provides a generalized view of life in Jalija and Zerek (the two halves of her borough, passionately designated by their old Ottoman names that few people outside of Dorćol would recognize today) and highlights her empathy and her sympathies.

The narrator processes her problematic relationships with her parents and describes how she took up training in an unusual sport to counter the unopposed cruelty—mostly, but not always, of young men—around her. Before she was even a teenager, she was training at boxing and judo, and her grim determination to be self-sufficient only grew with the force of events, such as her attempt to help a dying man on the street when no ambulance was available. But the novel never relents in pairing the ugliness of public life with what happened behind closed doors: the “ceaseless, inarticulate rage” of her hard-drinking father. These are, indeed, the “two fires” between which her childhood was squeezed.

And yet not everything here is grim: there are plenty of childhood memories—delicious street food, great music, running up Kalemegdan the hard way, all kinds of bonding experiences with friends—that leave their marks despite poverty. The inhabitants of this novel feel and suffer deeply, but they are mostly too young to come to grips with the main cause of the poverty, which is the violent breakup of the country. They do, however, miss Yugoslavia when it is gone. This point is important because the war tends to play arguably an outsized role in a lot of autobiographical fiction and creative memoirs published in Serbia over the past twenty years. Or, one could say, the strange and flawed and often hopeful or at least enjoyable creature that was Tito’s Yugoslavia has become an almost abstract object of yearning and allegory in too many novels. Iskra spends her time, refreshingly, in a more original and personal pursuit of solidarity and healing.

After all the bleakness, misunderstandings, and upheaval, what remains are abiding friendships and a deep and sometimes affectionate understanding of the rapidly changing city of Belgrade. And there is one more thing here: a merciful quantum of love, even—surprisingly, perhaps—toward her terminally ill father. This fine novel is looking for its English translator, and it deserves a great one.

John K. Cox

North Dakota State University