A Girl in Litland: The 2016 Neustadt Prize Lecture

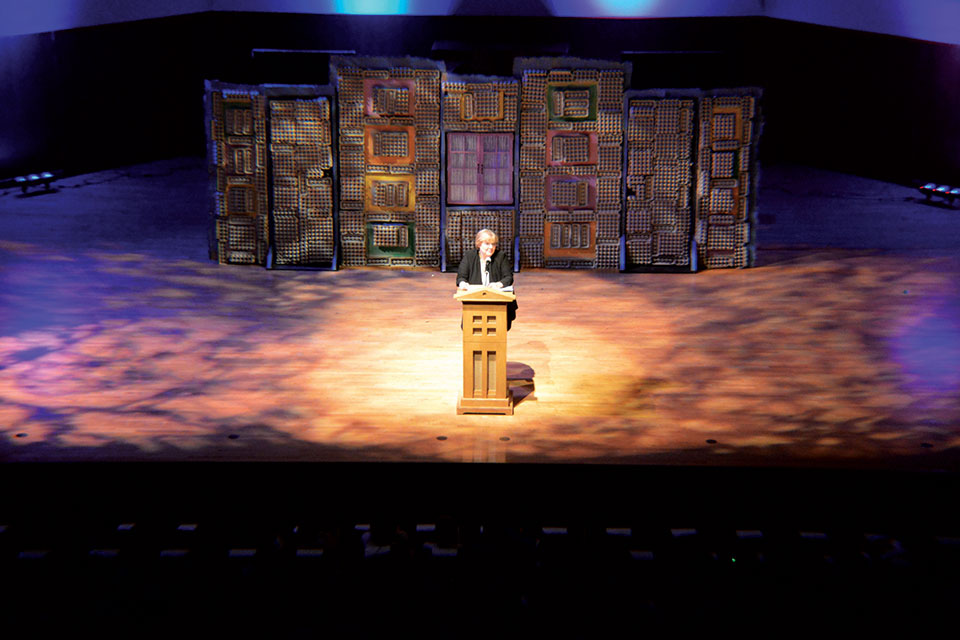

After watching the world premiere of the staged adaptation of her story “Who Am I?” along with several hundred attendees, Ugrešić delivered the following keynote to the rapt audience.

The first two books I wrote were for children. When I published my first book I was twenty-one. I soon gave up on writing children’s literature when I realized that I didn’t have the very particular god-given talent that only the exceptional writers for children possess. I still believe that the career of the children’s author—with the gift of a Lewis Carroll—is the most joyous career a writer could wish for, and it is, at the same time, a “natural” choice: writing for children means living in an extended childhood. I say this because adults work at jobs that are useful, while children work at tasks that have no practical application. Literature, too, is a nonuseful task. It has no price tag, there can be no compensation for it—just as a child’s drawing has no price tag—nor can it be manipulated, though many people are hard at work at precisely that, “manipulating” literature. Even writers, after all, do not hesitate to manipulate.

At a historical turning point for the cultural community it was decided that literature, this useless task, should be granted a more serious standing. The status of modern literature began at the moment when it became a subject of study at universities, and this happened only several hundred years ago. Any standing is vulnerable to change. In other words, a vast amount of time is needed to build a pyramid, even more to maintain it, but only a few short moments to tear it down. In this sense literature, as a system of knowledge devised and built by hardworking people over the centuries, is a fragile creation. Those who work at literature should keep this in mind. Perhaps it would be apt here to think back to Ray Bradbury’s cult novel Fahrenheit 451 as well as to the many postapocalyptic science-fiction movies. There are no books to be seen in the latter. At least I haven’t seen one. And besides, when the time comes for everybody to start writing books—and that moment, thanks to technology, is upon us—there will no longer be literature. This is because literature is a system that requires arbitration. The arbiters used to be “people of good literary taste”: theoreticians, critics, literature professors, translators, editors, and, don’t forget, the attendant mediocrities: the censors, the salespeople, the “Salieris,” the ideologues of various stripes—from religious to political. Today the market has anointed itself as arbiter, as have the readers. The market is allied with the “majority reader.” Authors are no freer as a result—along with politicians and entrepreneurs, today authors are expected to please the consumer, to lobby, blog, vlog, post, tweet, to be liked, to spread with diligence to their digital fan base who will support them and buy their books.

I was born into a world in which the first technological wonder was the radio. I remember waking up at night and turning the big dial to move the red line across to the stations inscribed on the display while I listened to languages I didn’t understand. Our radio was called a Nikola Tesla, and it had a green eye that glowed in the dark. I was born a few years after the close of the Second World War in a small country, poor and ravaged by war, where there was a pressing need to manufacture goods that were more utilitarian than those from a toy factory. That’s why I got my first “real” doll when I was already too big to play with dolls. In my early childhood, what I found sensational had nothing to do with toys but with books, the radio, and Hollywood movies for grown-ups: the text, sound, and image gave me the illusion of flight from my provincial little town into the grand, thrilling world. I envisioned the world with the help of books, and the role played by interactivity—to use contemporary jargon—was huge. The field of the imagination is more circumscribed today; the cultural industry has satisfied every need we could only have dreamt of before. Here are our “prechewed” products (Anna Karenina for Beginners), or streamlined, readapted, and commercialized versions of original works (Anna Karenina and the Zombies), or experiments such as the use of hologram books. The new media today are filling the space of the imagination to its last inch: they are taking the soul, time, and money of their “consumers” and leaving nothing behind.

In my childhood and even in my student days, publishing was not yet referred to as an industry, nor was there a literary marketplace, and the borders between children’s literature and writing for adults were not so sharply drawn. There were no psychologists hovering over the process of consumption; with passion we read whatever we could get our hands on. Thanks to the media and the marketplace, our taste today is standardized. The powerful industry nourishes every consumer capillary of the world. In the very poorest quarters of Kolkata where people inhabit space the size of a matchbox, they may be impoverished, but miniature screens (television and otherwise) glow day and night from their makeshift abodes.

In the bygone days of Yugoslav publishing there used to be an unpopular penalty known as the pulp tax. Those who chose to satisfy the more “pedestrian” tastes of the readership had to pay a special tax for the pulp fiction they published. If the tax for pulp were to be levied at a global level, this would amass a vast store of money, which could be used for publishing both high-quality and inexpensive books for a free and fine education, for teachers, for artists, for the creative folk. All this can be imagined, of course, but the only thing that defies the imagination is the decision of who would evaluate what fiction is pulp and what isn’t. And it bears mentioning that the terms pulp fiction and kitsch have faded from the parlance. Some thirty years ago kitsch was still a subject for discussion and a focus of research among theoreticians of art and literature. Then the powerful global market elbowed the concept of kitsch out of its vocabulary. Anything that separates the “wheat from the chaff” is undesirable in a global marketplace that works to sell everything, and sell as much of it as possible.

There are key tags to be found in the vocabulary of the brilliant sociologist Zygmunt Bauman that have relevance not only for our age but for the culture industry, including that of literature right now. One of them is waste. Our industrially hyperactive civilization generates, among other things, waste. With the most popular commands of copy and paste there appears the need for a command to save. Our digital age is shaping the mind-set and physicality of the digital human. Our fingers are growing thinner, longer, and more adept, but we’re keeping ophthalmologists busy as we constantly adjust the lenses in our eyeglasses. Our language, too, is changing. Now, not just children but adults rely on abbreviations and emoticons. Our emotions, too, have changed, as have our sensors for reception, our codes, our ways of communicating, and, foremost, our sense of time. We feel we’re immersed in an all-accessible, domineering now. In this sense a feeling of cultural discontinuity has crept into older specimens of the human race, such as myself, despite the all-accessible search engines that can connect us, in seconds, to bygone times. In parallel to the emancipating and powerful sense of control through digital devices such as the smartphone, a liquid fear, as Baumann would put it, has come to dwell in people, a neurosis of insecurity (perhaps this being our need to leave millions of selfies in cyberspace to confirm that we lived).

The story “Who Am I?” was born out of a sense not only of security but of literary plenty thirty-three years ago, at a time when I was as happy as a mouse nesting in a wheel of cheese. My wheel of cheese was the library, a university job, the certainty that literature was autonomous and that the only thing worth dedicating myself to was literature. The short story that has been staged by the students from the OU Helmerich School of Drama, directed by Judith Pender, came about out of a powerful feeling of literary well-being, of continuity. I was intrigued by the idea of a defamiliarized reading within a profound familiarization with world literature.

Internet literature, the fan fiction I explored while writing my essay “Karaoke Culture,” is today guided by a similar principle, but the canon is different. These are not classic works of the literary canon but belong to a new, contemporary canon of millions of readers and viewers: Harry Potter, Twilight Saga, Hunger Games, and others like them.

We should invest all our energies in supporting people who are prepared to invest in literature, not in literature as a way to sustain literacy but as a vital, essential creative activity, people who will preserve the intellectual, the artistic, the spiritual capital.

Because of all this, and perhaps because of my unjustified feeling that the system of literature as we know it is on the way out—what with digital civilization taking over Gutenberg civilization—we should invest all our energies in supporting people who are prepared to invest in literature, not in literature as a way to sustain literacy but as a vital, essential creative activity, people who will preserve the intellectual, the artistic, the spiritual capital. I couldn’t have dreamed that one day a student theater in Norman, Oklahoma, would be putting on the first-ever staging of my story, written thirty-three years ago. Literary continuity, therefore, does exist, and the fact that it describes an unexpected geographical trajectory only heightens the excitement.

The literary landscape that has greeted me in Norman has touched me so deeply that I, briefly, forgot the ruling political constellations. I forgot the processes underway in all the nooks and crannies of Europe, I forgot the people who are stubbornly taking us back to some distant century, the people who ban books or burn them, the moral and intellectual censors, the brutal rewriters of history, the latter-day inquisitors; I forgot for a moment the landscapes in which the infamous swastika has been cropping up with increasing frequency—as it does in the opening scenes of Bob Fosse’s classic film Cabaret—and the rivers of refugees whose number, they say, is even greater than that of the Second World War.

A continuity of literary evaluation does, nevertheless, exist. The knowledge of what is good literature has not been lost for good. This is a moment to recall Vladimir Nabokov and his words, which belong to the realm of sorely needed literary evaluation:

There are three points of view from which a writer can be considered: he may be considered as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter. A major writer combines three—storyteller, teacher, enchanter—but it is the enchanter in him that predominates and makes him a major writer. . . . To the storyteller we turn for entertainment, for mental excitement of the simplest kind, for emotional participation, for the pleasure of traveling in some remote region in space or time. A slightly different, though not necessarily higher mind, looks for the teacher in the writer. Propagandist, moralist, prophet—this is the rising sequence. We may go to the teacher not only for moral education but also for direct knowledge, for simple facts. . . . Finally, and above all, a great writer is always a great enchanter, and it is here that we come to the really exciting part when we try to grasp the individual magic of his genius and to study the style, the imagery, the pattern of his novels or poems.

We are met here at the Neustadt Festival, an occasion for celebrating the enchanter, whoever he or she may be. We have gathered to celebrate all those who have been, who are, and who will be our past, present, and future—enchanters . . .

Norman, Oklahoma

October 28, 2016

Translation from the Croatian

By Ellen Elias-Bursać