“An Inexhaustible Responsibility for the Other”: A Conversation with Carolyn Forché

This three-part interview with Carolyn Forché took place over the course of the past year and a half and was recorded at three different locations: Carolyn’s house in Bethesda, Maryland; in the bistro of the Washington Square Hotel in New York City; and in her office at Georgetown University. (With regard to the addendum that appears at the end of the interview, I emailed Carolyn following the recent election to ask her if she would like to comment on the results. She responded the next day with a timely paragraph.) I had originally hoped that Carolyn and I could complete this interview in one sitting, but we agreed at the conclusion of our first conversation that we needed more time than a single afternoon to do justice to the arc of both her poetry and her career. Consequently, our subsequent interview sessions focused with greater probity on the “main things” of Carolyn’s multifaceted vocation and avocation as a poet, witness, and scholar. Although we didn’t conclude with any sense of final closure, I felt our conversations reached increasingly higher levels of clarity in their exploration of the ideas, poems, essays, books, vicissitudes, failures, and hard-won successes that have distinguished Carolyn’s eminent career.

Part 1: “Language in the Aftermath of Extremity”

Chard deNiord: I’d like to start by talking about your thoughts on the Poetry of Witness today. You’ve recently edited another prodigious anthology with Duncan Wu titled The Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500–2001, which follows up your first anthology Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness, published in 1993, and focuses ambitiously on the tradition of the poetry of witness in the Western canon. So now you’ve succeeded in collecting poetry from both the past and the present in two complementary anthologies that testify to memorable expressions of human extremity—volumes that are heroic in their scope and exhaustive in their research. I imagine you must feel both exhilarated and a bit saddened by the completion of this project that began twenty-five years ago.

Carolyn Forché: I think the idea of Poetry of Witness was misunderstood in some ways. It was read by some, at that time, as political in a narrow and particular way. “Witness” was understood as “political,” and certain responses were suffused with ideological assumptions. As you know, there was (and still is) a resistance to poetry that seems message-bound, arising from an intention to persuade in some way. But it goes beyond that. There was resistance to the idea that a North American poet’s work could reflect upon an experience or contemplation of contemporary events without being polemical. And so the history of my involvement with this idea is maybe one of the things that you wanted to talk about.

deNiord: Yes, you wrote in your introduction to Against Forgetting that “the poetry of witness is itself born in dialectical opposition to the extremity that has made such witness necessary. In the process, it restores the dynamic structure of dialectics.”

Forché: One would hope. That’s an ambitious claim.

deNiord: Yes, but that is exactly what you’re talking about, it seems to me. You’ve said, “For decades American literary criticism has sought to oppose ‘man’ and ‘society,’ the individual against the communal, alterity against universality. Perhaps we can learn from the practice of the poets in this anthology that these are not oppositions based on mutual exclusion but are rather dialectical complementaries that invoke and pass through each other.” And so in that very polarized world that we grew up in, during the Cold War, that’s exactly what was taking place.

Forché: Well, there were also poets writing during the Cold War, especially during the Vietnam War, and throughout the civil rights movement and other struggles in the US and abroad. People wrote poems that were cries against injustice, and they were inviting poems to be read in the way that we read all poetic literary works of art. In their impulse and urgency these poems might not transform their subjects as expected in literary works of art. But they weren’t written as literary works of art. I came of age in that time, as I began writing at the age of nine; I began as a poet rather than a political activist.

deNiord: So your mother told you to write about something?

Forché: My mother, yes. Before the seven of us were born, my mother attended Marygrove College in Detroit for two years, a college founded by the Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. My parents were very religious Catholics, and my mother was a bit of a mystic, as I realize now looking back. Her mysticism was also shot through with moments of psychic awareness of some kind. She had the ability to know things beyond her senses. She was a bit afraid of this psychic gift.

deNiord: It must have frightened you.

Forché: It was frightening at times for her and for us. But she also wrote stories and a lot of poetry, most of it very formal, metered and rhymed. She published some of the poems in newspapers before we were born. I was the first of seven children. She married my father after the war, and in good Catholic tradition had seven children within ten years. We went to a Catholic school, Our Lady of Sorrows, and we were crowded in our house, where we lived the liturgical year, that is, according to the seasons of the church and the requirements of the sacraments. We lived in the year of the church, that is, rather than the world—in fact, we were quite isolated, I think, and sheltered in that life. When I went out into the world, I discovered that not everyone knew when it was Advent or that there was a Gaudete Sunday.

deNiord: Do you remember the first thing you wrote when you were nine?

Forché: Well, it was a very boring poem. My mother showed me poems. I don’t remember whose. They were from her very thick college textbook. I was reading some of these. I wish I remembered whose. I was trapped in the house because of a blizzard, and there were lots kids by then. There would have been maybe six of us. It was a blizzard, so I wrote the poem about snow. And then I wrote another and another. I don’t know what those were about, but I remember the one about snow. And I remember that I wrote it in the same meter as the poems I had been reading: iambic pentameter. And I gave the poem a rhyme scheme, and my mother was curious and interested in this writing that I was doing. She got me settled into it and said, “You know, you should read poems, and you should keep writing them,” and eventually she got me a desk and a typewriter, a manual typewriter, and I could make my poems look like the poems that were published in books on this typewriter. I was very young, but it was good for me because I had no contemporary poetry models. I don’t think I read anything written after 1900, so I didn’t know about modern poetry.

deNiord: But you had an ear, at that age, for meter? You were able to hear iambic pentameter without being taught.

Forché: Yes, I could hear it but couldn’t scan it. Scansion reminded me of math. I’m not good at math. I could hear the meters and the rhythm of the language, but notating it was always a challenge. When the teachers started making little slash marks between the lines and accents over the syllables, I felt about that as I felt about combining numbers and letters in algebra. Just tell me what “x” is and I’ll be fine. I don’t have mathematical ability, and I think this is because of the intensity of my development in language. I was writing a lot of poetry, and then the nuns had us writing paragraphs.

deNiord: Prose poems?

Forché: Prose poems! They were! But they were called “paragraphs,” and they were supposed to have a beginning sentence, middle or “body” sentences, and a concluding sentence. Mine were variously shaped, and I would just call the first sentence my beginning sentence, whatever sentence was first. I would say now, some of them were sudden fictions, some of them were a hybrid of short prose forms that have since emerged. But they were the nuns’ paragraphs to me. We wrote them all the way through school. I had a problem because in the beginning, the nuns thought that I was copying my paragraphs from somewhere.

deNiord: From a book?

Forché: Somewhere. They couldn’t find where. Well, they couldn’t ask Google in those days.

deNiord: But they were impressed enough.

Forché: I now realize that that’s what it was, but at the time I thought that they were suspicious of me or didn’t like me or thought that I was cheating. And I begged them to believe me. This went on for a long time. They didn’t want to give me good grades because they thought that I was just taking paragraphs from somewhere. So finally one day I told the nun I wanted to stay after school and write a paragraph in front of her. I said, “You can give me any topic. I’m going to sit at the desk, and I’m going to write one for you. And then you will see that I write these myself.” I was scared because I didn’t know if it would turn out all right. I wrote something about envisioning the root system of a plant below the soil mirroring the plant above the soil. I no longer have it, but she took it from me when I was finished and stood in front of me in her Dominican habit. They were Dominicans and were very strict with us. She read it, looked at me, and said, “You’re dismissed.” I walked away. She didn’t say anything else. But that was the end of that.

deNiord: But you had proved to her that—

Forché: But she didn’t say anything, she didn’t—

deNiord: She didn’t say, “Good job” or—

Forché: Or “we were wrong” or “we are sorry.” Of course that wouldn’t happen in my childhood. Children were never—

deNiord: Isn’t it ironic that way, that one of your few prose poems, I think it’s your only one—

Forché: Yes, well, I have a prose poem in Gathering the Tribes, or maybe two, I don’t remember.

deNiord: Okay, yes, that’s right, the longer ones.

Forché: I haven’t written many of them.

deNiord: But were you thinking about that when you wrote “The Colonel”?

Forché: No. Well, actually, you know what? You might be on to something. I didn’t write it as a poem. I had come back to Virginia. It was winter. I remember that it was snowing.

deNiord: This was in 1979?

Forché: Yes, and I remember thinking that I was going to have to remember everything because one day I would write about this. Not in poems, necessarily, but I thought perhaps in an essay or something. I wanted to remember details. I wasn’t worried about the horrific thing the colonel had done but about forgetting the little bell and the broken glass. I thought I should write it all down and put it away, that someday I would have it if I needed it. The prose paragraph that became “The Colonel” was written all in one night. I put it away because it wasn’t poetry, I thought, but prose. I thought it wasn’t ready, and there was so much to think about before writing of those times. That paragraph became mixed up in the manuscript of poems which became The Country Between Us.

There was a scholar at the University of Virginia, Daniel Albright. I just learned that he died a few years ago. At that time, he had written a book on Yeats. He was a brilliant, wonderful scholar. He was really very generous toward me. Many of the older professors were dismissive of living writers and poets. Daniel took the folder of poems and offered to read them and let me know what he thought. When he returned the folder, he offered generous feedback but singled out “The Colonel” as the strongest poem. I remember saying, “Oh! That’s a mistake. That one is not supposed to be there, that isn’t a poem.” He told me that I was wrong and gave his reasons. “It is a poem, indeed,” he said. “It’s a prose poem.” He showed me all these different things that were happening in the language. I said I was saving it for something else, and he said, “No, don’t save it, you never know what’s going to happen. Leave it in this book. And if you want to include it in something else later, you can do that.”

I remember thinking that he probably was giving the right advice. After all, he had a doctorate, which I did not, and he was an expert on Yeats. I left it in the manuscript. And I was a little worried that, once it was published, the colonel, who was then still living, would see it. As it turned out, years later, the friend who was with me that night, who had brought me to the colonel’s house, told me that he himself had shown the poem to the colonel.

deNiord: And his response?

Forché: I don’t talk about this much. He showed “The Colonel” to the colonel. My friend told me this rather casually, while visiting me in the United States. “I showed him by the way,” he said. “I showed him the poem.” I was flabbergasted and asked him why ever he would do such a thing. He assured me that it was “all right, that the colonel had liked the poem and had even had it laminated to carry with him. He was very proud of having a poem written about him.” I asked him how it was that the colonel did not see this as a negative portrayal. My friend answered, “He doesn’t see, but he remembers the night, and he thought you wrote about it very well and he still feels the way he felt and he is very happy to be in a poetry book.” This surprised me.

Later, the journalist Doug Farah, who worked for the Washington Post, gave me a clipping of a story he had written for the New York Times. The story was published on May 20, 1986, a month after our son was born. We were living in Paris by then, so we didn’t see the story for some years. Mr. Farah said, “I’ve heard that there are people who have doubts about the event in your poem, so I thought this might help you.” The article reported on the practice in El Salvador of cutting off ears and keeping them to prove kills or for other reasons. I have wondered, over the years, why the poem was so uniquely disturbing. The event was not the worst that I witnessed or that others had.

Lately, I have thought it may have affected people the way it has because the setting was a dinner party, one in which anyone might see him or herself in normal circumstances, and that it was the intrusion of violence upon these normal circumstances that caused the problem. But the doubts were also because the United States government during that time, and well beyond the conclusion of the war, was denying the existence of death squads, most especially within the military. There was a concerted effort to counter information and reports coming out of El Salvador that contradicted or threatened US policy in the region. Journalists and others found themselves under pressure. There was a list of those who were not to be trusted, those who didn’t toe the embassy line, those who didn’t cooperate. I was told years later that even I was on that list. I thought it interesting that US government officials would be threatened by a poet.

deNiord: This is fascinating because you were reluctant to go to El Salvador initially since you felt it was a journalist’s job to report on what was happening there.

Forché: I thought that, yes, at the time Leonel Gómez Vides first visited me and invited me to El Salvador.

deNiord: He was the poet Claribel Alegría’s nephew, right?

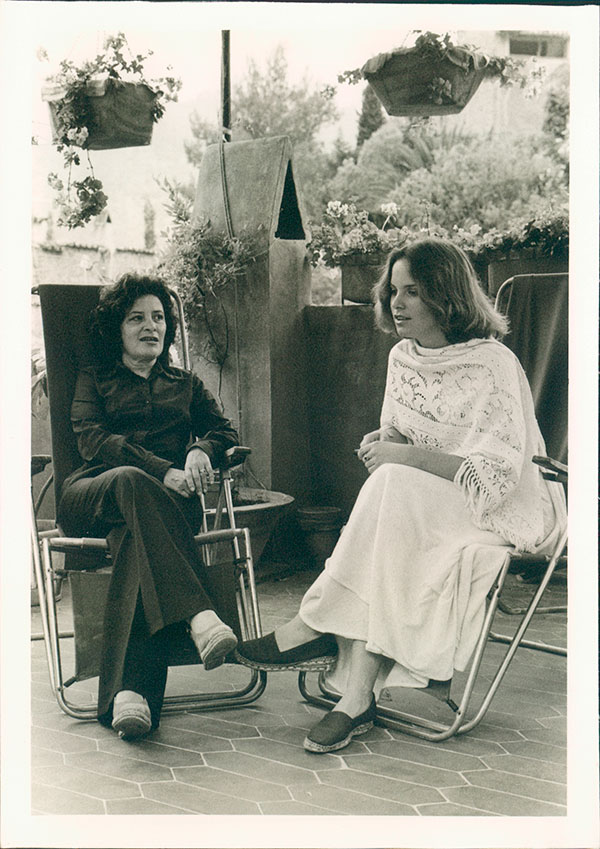

Forché: Yes. Well, everyone calls everyone else “cousin.” Prima, primo. I believe, however, that he was a nephew. I’m writing a memoir now that begins with Leonel paying me an unexpected visit in California. Claribel’s daughter, Maya, had told him that I had been working on translations of her mother’s poetry.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: Maya was pleased that we were translating her mother’s work, as Claribel had never before been translated into English.

deNiord: She was living in Majorca?

Forché: Yes. Maya and I had met in San Diego, California, while I was teaching at San Diego State University. Maya’s then-husband was a colleague of mine there. We became close friends, and gradually she introduced me to Alegría’s poetry. I was rather surprised that her work had not yet been translated into English, as she had been translated into so many other languages. She seemed to be a prominent poet from Central America and was living in exile in Majorca. I had just published Gathering the Tribes, and I had the naïveté, I was quite a young person—

deNiord: Twenty-six.

Forché: Yes, and I was a young twenty-six. I had thought that, once I had published a book, poems would come so much easier, that I would just be able to write, because now I was a poet. Of course, the opposite was true, it was much harder. I went through my very first dry spell. I thought that I had sacrificed my ability to write—sacrificed it to publishing, to publication. The price for this was that I was no longer able to write. I desperately wanted my writing back and publication to be gone. I still have the problem of not feeling joy at publication. It terrifies me, which is probably one of the reasons I publish infrequently. There are other reasons, but that’s one reason.

deNiord: This was after Gathering the Tribes had been published.

Forché: Yes. I thought then that if I translated the work of another, I would be able to sort of slip back into my own writing without being seen.

deNiord: And you were learning French at this same time?

Forché: I had been studying French and Spanish. I studied both in college. I thought I had enough Spanish. I bought the Mariano Velázquez de la Cadena Spanish dictionary and the 500-word conjugations, and I set to work. Very shortly, of course, I realized that I was ill-equipped to translate this work, and I came back to Maya and said, “I can’t do this because these poems come out of circumstances and experiences very unfamiliar to me.” I didn’t understand how to discern figurative from literal language. I thought, when she wrote about mutilated hands, hands that had been mutilated by an axe, that this had to be figurative, couldn’t have actually been—that’s how naïve I was. So I said I don’t know anything about Central America or its history. I don’t know anything about torture or life under military dictatorship. I just don’t think I’m equal to these poems. But Maya wanted the poems translated into English, and so she invited me to accompany her to Spain for the summer, and we would all work together. In Spain, I translated the work with Maya, but it was a struggle, and it was a surprisingly depressing time.

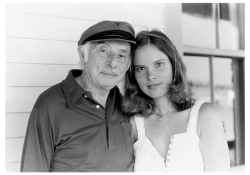

Many writers and poets were forced into exile at that time from the “Dirty Wars” in Argentina and Chile. Franco had just died, and this created an opening for the exiles to go to Spain, with the added advantage of a common language. Some of them were guests that summer at Claribel’s house. She had many friends among the Latin American intelligentsia and literary elite: Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Mario Benedetti, Augusto Roa Bastos, Cristina Peri Rossi. The English poet Robert Graves lived down the road, but he was already quite ill then. But even he would join the group that gathered on Claribel’s terrace in the late afternoons to talk. He would come to these meetings on the terrace overlooking the Teix. I was a young girl, had just turned twenty-seven. A person of twenty-seven is not a child, but I was naïve and had never been to Europe before and knew nothing about the world yet; I now realize that I was simply unsophisticated.

Instead of having a beautiful and wondrous summer, although it was so in many ways, I became depressed. It seemed that in all the conversations, it was thought that the United States was behind the problems of Central America, that US policy was wrong-headed at best, and that we were implicated directly in the support of the dictatorial and murderous regimes. And even though I had marched against the war in Vietnam, I didn’t quite understand how very wrong we were in so many ways in so many countries, beyond Vietnam. I hadn’t been paying attention because I was not, at heart, politically inclined. But I emerged from that summer wanting to do something. It is an impulse I have recognized in certain of my students all these years. Something was pulling, pulling against the festivities of the island and the late nights and the sea.

I was isolated when I got home; I couldn’t even talk about it. I finished the translations, Flores del volcán (Flowers from the Volcano), but at first nobody wanted to publish it because no one had ever heard of Claribel. I had the manuscript in the drawer. I joined Amnesty International, and they had at that time something called the Urgent Action Network, and you wrote polite letters to dictators begging for mercy for political prisoners, and so I wrote a lot of those. Then Leonel Gómez Vides came into my life, with his very different idea about the place of poetry in the world. He wanted a poet to come to El Salvador. He knew that war was coming.

deNiord: As I recall he said, “You know what happened in Vietnam is about to happen again.”

Forché: Yes, he said this, but I didn’t believe him. I said no, we’re not going to be involved [in war] again. Because that’s how, shall we say, dumb I was. But he wanted a poet.

deNiord: He really wanted a poet to go there, a poet who was going to witness as well as to report on the atrocities.

Forché: He had this idea that it was important for a poet to see this in advance, so that when war began, this poet could somehow speak to her countrymen about the situation in a way that was much more serious, Leonel thought, than journalism.

deNiord: And Archbishop Óscar Romero thought this too.

Forché: Yes. They saw poetry differently than we do. I was uncomfortable most of the time telling people in El Salvador that I was a poet because I thought it was much more important in the context of that poverty and oppression to be a doctor or a human rights lawyer, or something like that. So to be a poet was something a bit embarrassing.

deNiord: Or even a journalist.

Forché: Yes. Or a journalist. But I found out as time went on that when they did discover I was a poet, the reaction was something I didn’t expect. Very serious and impressed. And loving. That was something I was not used to. Initially, I told Leonel, “I think you need a journalist.” And he explained why he didn’t want one. He said, “Soon we’ll be overrun with journalists. When the time comes I need someone to understand this situation deeply, on a different level. I’m not interested in ideology. I’m interested in your awareness and your comprehension. Yourself directly. That’s it.” He believed that poets have a capacity to read the world in an unusual way that didn’t involve illusory notions of objectivity.

deNiord: He was also interested in sort of the essential language of poetry.

Forché: Yes.

He believed that poetry would affect the world. And it would affect the world not only in our time but in the times to come, because in Latin America, and in many other countries, and in our own country, I would argue, poetry does survive the age.

deNiord: Right, its memorable speech.

Forché: Yes, memorable speech, and he believed that poetry would affect the world. And it would affect the world not only in our time but in the times to come, because in Latin America, and in many other countries, and in our own country, I would argue, poetry does survive the age. We’re still reading Walt Whitman’s poems about nursing soldiers wounded in the Civil War. We’re still reading.

deNiord: He had faith in the power of poetry.

Forché: That’s right, he had this. There were things that I didn’t know in the beginning and that I came to know. Some of them I came to know recently—some things about him I didn’t learn until after his death. Leonel was not a religious man himself, but he believed that there should be voices who were not allied with any political faction or party or segment of the population. He believed that there should be voices that could be heard above the cacophony of the political arguments. But he believed there could be such voices.

deNiord: Well, he had chosen you as that voice.

Forché: But he didn’t really, he didn’t know me.

deNiord: But for him to travel that far to meet you . . .

Forché: Well, because of what he’d heard. This is what he knew: she teaches at San Diego State University, she is a poet who has won a prize from Yale, she has a grant so maybe she’s free to travel, she’s interested in Central America or why else would she be translating Claribel? So all these things fell into place for him. He didn’t have another poet. He knew that Claribel was not going to come to El Salvador because she was older and had a family and was living abroad. So why not take the chance and see what happens? He often proceeded intuitively. But he also thought the war wasn’t going to begin for three to five years.

deNiord: He was wrong about that.

Forché: It was much earlier and took him by surprise. Everything that he thought would happen, that he predicted would happen, did, but much sooner. I remember how surprised he was that his timing was off. He was only thirty-seven at the time. I thought of him as rather invincible. He was fiercely intelligent, and I imagined that this meant that we were both somehow bulletproof.

deNiord: To go back to “The Colonel” for a second, you didn’t want to go to El Salvador because you didn’t think your poetry would resonate in a way that Leonel Gómez thought it would as both poetry and reportage?

Forché: I went to El Salvador to learn more, to improve my Spanish. He never asked me to write about anything. What he wanted, I think, was for a poet to speak out here in the United States, with the moral authority conferred on poets in Latin America. The word of poets meant something there. He imagined that this might be true in the United States as well. I tried to explain that it was different here. I don’t think he believed me. I also could not have written poems, necessarily, about the experience, because poems don’t come from the will. That’s not how poems arise.

It was really comic what happened between us because he not only thought that you could write about whatever you wanted in poetry, he thought it happened fairly quickly. You just sat down and wrote the poems. He also thought that because I was a poet I could also write, you know, an article for The Nation or. . . . Writing, writing, writing. It’s all the same. Writing for him was just something that gushed out of the pen. But he wasn’t listening. He said, “Yes, yes, yes you will be fine.”

deNiord: So, like many Latin American poets and writers. I think of Martín Espada, for instance, for whom there is very little difference between politics and poetry. The language of politics finds its way into poetry. It’s very . . .

Forché: Normal.

deNiord: Because of their tradition of poetry as news.

Forché: It’s also because it’s in the surround. If you are a poet in New England, you might enter into a certain natural world, for example, a seasonal world. You’ll see, you’ll notice certain things. You’ll notice perhaps geese migrations and snowfalls and bitter winds. Well, if you’re in a country like El Salvador, you see hunger, poverty, even if you don’t see violence you see all of that. This is just part of your world. And so it enters into your sensibility and awareness, your consciousness.

deNiord: In a way that most middle- and upper-class Americans can’t fully comprehend.

Forché: I think the poets who went to Vietnam were affected by these things, and you see that in their work. Poets in the US who are exposed to poverty, suffering, and oppression see it. I try to be careful about imagining what Americans can or cannot see, but I have encountered the proscription in the literary world against certain subjects entering poetry. When I finished my second book I was unaware of this, really, mostly out of ignorance. I didn’t realize that there were things that American poets were not supposed to write about.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: But I didn’t know that because, as I told you, I was young and had been reading poets in translation. I didn’t think there was anything that one couldn’t do. I loved Anna Akhmatova. When I was twenty-three and doing health research in the Library of Congress, I found Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward’s Akhmatova, and that was thrilling to me. She led me to Osip Mandelstam and he led me to Marina Tsvetaeva. I was reading so much in translation, working my way through René Char in French, especially his Leaves of Hypnos. And then came the Spanish-language poets. There just didn’t seem to be barriers or restrictions. But apparently there were, at that time, for some of the poets of my own country and tradition.

deNiord: So maybe your poem “The Colonel” bridged the gap between “poetry” and “the news” because the American readership was not intimidated by it as poetry, by the appearance of difficult language on the page?

Forché: It has the shape of prose.

deNiord: It has that shape which avoids the terror of the line.

Forché: It can’t go into lines. That poem can’t be lineated.

deNiord: So it slipped in the backdoor of American readers.

Forché: Well, the door was wedged open by Professor Albright.

deNiord: He wedged the door, but once people read the poem, they got it. They felt both informed and maybe proud of themselves for having understood a contemporary poem.

Forché: I believe it’s not difficult.

deNiord: It was accessible poetic language that was both striking for the news it was conveying and its “adequacy,” as Emily Dickinson would say, as a prose poem.

Forché: Ironically, you’re absolutely right.

deNiord: It came across as a kind of literary journalism that conveyed important news. You had succeeded at exactly what Leonel had asked you to do.

Forché: But readers were struck by the core violence in the poem.

deNiord: Oh, absolutely.

Forché: It got through.

deNiord: There are, of course, other poems in The Country Between Us that witness also to the atrocities taking place in El Salvador at the time.

Forché: But it was the prose poem form; perhaps you’re right. I see what you’re saying. You’re talking about the general readers’ aversion to or fear of lineated literary art. I would argue that this also enabled Claudia Rankine’s Citizen to cross into a wider readership. Lineated poetry, perhaps, intimidates.

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: It intimidates and frightens. But I didn’t write it with that in mind.

deNiord: No, but in a way I think, even probably unconsciously, you were going back to your paragraphs.

Forché: Yes. Paragraphs, yes. That’s right. I probably went to the ground of writing in my childhood.

deNiord: It opened an enormous door.

Forché: Yes. Well, you know that was a puzzling thing.

* *

Forché: When I left El Salvador I received an invitation to come and work in a prison in Alaska. Randall Ackley of Anchorage Community College had founded a program called “University Within Walls” in the nine formerly territorial prisons of Alaska. He asked me to come up and teach in his program. I was doing that when The Country Between Us was published. It had been rejected several times, which is why it appeared, finally, when it did.

deNiord: What publisher did you send it to first?

Forché: Well, several rejected it. Several publishers rejected it.

deNiord: But Margaret Atwood put in a good word, didn’t she?

Forché: She sent me to the agent who sent it to these publishers. She said you have to get this out. You can’t keep this manuscript in the drawer. It was in the drawer. Margaret Atwood told me to stop hiding this work. I sent it to an agent at her recommendation. Agents move fast. The agent was wonderful. And brilliant. She sent the manuscript finally to Ted Solotaroff, who was, as you know, an engaged person, politically aware. He knew what he had in his hands because El Salvador was for the first time coming into the news. It was being written about in the newspapers. People in the US were starting to be aware that something was wrong there. It was the time of the death squads.

So, when The Country Between Us was published by Mr. Solotaroff, he rearranged the order of poems in the book, placing the El Salvador poems in the front. He chose a photograph of me for the cover. I didn’t see this photograph until the book came out. He told me that he obtained it from American Poetry Review. I didn’t want my picture to be on the cover. I didn’t mind it for the back jacket flap if it was small. In any case, his job is to sell books. But this got me into trouble with the poets. Then somehow the book got into the hands of two syndicated newspaper columnists, Nicholas von Hoffman and Pete Hamill. These two men wrote columns about El Salvador, mentioning my book and asking why this wasn’t more in the news and why we weren’t hearing more from the press; why we were, essentially, getting this news from a poet. Thank you, William Carlos Williams. These columns appeared in more than two hundred newspapers within a week. Then People magazine published a little thing about it, and Time magazine too.

deNiord: And it became a best-seller.

Forché: Yes. Meanwhile, I’m up in the prison, in this seven-gate lockup, teaching poetry to twelve medium-maximum-security prisoners.

deNiord: So you left San Diego?

Forché: Oh no, I had long been away from San Diego. I had taken a job at the University of Virginia, and then, briefly, at the University of Arkansas, and then back, as an adjunct, in Virginia. And then I went to teach in the prisons. That was an interesting experience in itself. But when I returned to Charlottesville, where I had been living, I said something about my new book to someone. Whatever it was I said, the reply came, “You don’t know what’s happened?”

deNiord: You hadn’t been reading the newspapers?

Forché: I hadn’t heard anything about it. No, the clippings were sent to the agent, and the agent collected it all. I didn’t really know. I was in Alaska. Nobody knew how to get in touch with me. I was teaching in the Lemon Creek jail in Juneau. I found the news of the response to my book really shocking; it shocked me that the book had sold, I don’t know, thirty or forty thousand copies that quickly. And also that it was controversial. And that I was being taken to task for writing political poetry, despite that my immersion in El Salvador had been actually with Christian base communities and with nuns and priests, with Monsignor Romero and the poverty and the great injustice, having to run from people, everyone threatened by death squads and dying brutal deaths.

In the United States, as far as I could tell, it meant something loosely oppositional to the status quo. “Political” was a label, affixed to people who variously brought to light anything that seemed to contend with dominant thinking.

deNiord: But witnessing a lot of this.

Forché: Yes, but I wasn’t thinking primarily in political terms or didn’t think I was. I was surprised that my work was being read as political poetry. I wondered what was meant by that. I knew that “political” was a pejorative term, but I didn’t know what they meant, because in El Salvador if you’re political, you go to meetings every night, you’re in a political party, you follow orders, you are in a disciplined, structured, political group. In the United States, as far as I could tell, it meant something loosely oppositional to the status quo. “Political” was a label, affixed to people who variously brought to light anything that seemed to contend with dominant thinking.

deNiord: There’s this fascinating dialectic going on up to this point and maybe even beyond this, between what you’re calling your naïveté and the profound effect that your work is having politically.

Forché: I have to say, I have to claim the naïveté because it was true. It would be very nice to say, oh yes, in my view, etc.

deNiord: Yes, but you wouldn’t have gone to El Salvador without your naïveté.

Forché: No, because who would?

deNiord: But I think a lot of the misinterpretation that was going on lay in people’s thinking that you went to El Salvador purposefully.

Forché: But who would do something like that? No one. No one sane.

deNiord: You were smart, young, celebrated, and ambitious.

Forché: No. No one sane would do that.

deNiord: And you knew exactly what you were doing when you went to El Salvador and so forth—

Forché: If I had known what was going to happen, if I had been sophisticated at that level and could imagine or extrapolate from present circumstances what would unfold, I would have been too afraid to go there, I think.

deNiord: But you were a naïve poet who was actually writing a history, a documentation that nobody else was writing because they didn’t possess the same combination of traits—naïveté, courage, and nascent passion to witness along, of course, with your poetic talent.

Forché: Well, they couldn’t do it. They weren’t there.

deNiord: But the fact is that you were there because of the sequence of events that we’ve just talked about.

Forché: Right. So it was all rather miraculous in a way. And I learned a great deal. It was a very rapid-immersion education. I didn’t keep the naïveté. That lifted away.

deNiord: After you published The Country Between Us, did you feel compelled at all to return to El Salvador?

Forché: Monsignor Romero and Leonel wanted me to return to the US to speak about the situation. I came back to the US a week before Monsignor Romero’s assassination. I’d had encounters with death squads while in the company of other people. Each time, fortunately, we escaped being taken.

deNiord: You wrote a poem about that in which you ask suddenly, “Am I going to die tonight?”

Forché: Right. Yes, gosh. During those occasions, there could have been more, but I wasn’t aware of them; those three occasions were absolutely horrifying. I was worried about my parents. I was worried whether I would be able to endure it—not death but what usually happened before death. But I survived, and many did not. I lacked confidence in my ability to fulfill what I perceived as my obligation. The last time I saw Monsignor Romero, I told him that North Americans don’t listen to poets.

deNiord: But he didn’t listen.

Forché: No.

deNiord: Your commitment to remain in El Salvador at the outbreak of civil war in 1979 reminds me of Anna Akhmatova’s response in her poem “Requiem” to the woman who asks, “Could one ever describe this?”—meaning, the horror of Stalin’s executions and imprisonment of political prisoners, including her and Akhmatiova’s sons. “I can,” Akhmatova replies in her poem, just as you responded with similar confidence to the challenge of witnessing to the atrocities in El Salvador.

Forché: I had that poem in my head too. I can put it on paper. But it doesn’t mean that most people in the United States will care.

deNiord: The point was describing it, trying to describe it.

Forché: I wrote only seven poems about that time. When I write, I don’t imagine writing about a certain thing. I sit and I wait, and maybe an image or a sound or a line for the poem comes. I work, and I revise a great deal. But I can’t initiate a poem about a certain subject. I wrote seven, and that was all. I can’t sit down to write poetry deliberately, consciously, or intentionally. This is interesting to me because the accusation about political poetry is that it is overburdened by its intentionality.

deNiord: Or that poetry is lost.

Forché: It gets lost in the message-driven utterance of the poem, and I thought, well, that’s not how it works for me. So anyway, I got back here and I was fine, I thought, and very committed to the work of opposing further military aid and intervention, but I was traumatized, as I now understand. I didn’t know this at the time. And my husband, whom I met in El Salvador, was also traumatized. We were perfect for each other.

deNiord: Equally traumatized.

Forché: We may have been drawn together in part because we understood each other as no one else did. He was a photographer. He had made photographs in and around wars in Nicaragua, Lebanon, El Salvador, and other places. Because of the unusual attention the book was garnering then, I received many invitations to universities, colleges, rotary clubs, and churches. I was on the road, I think, two hundred days of the year. It was relentless. I was sleeping on couches and eating little cubes of cheese and after the readings there would be gatherings of solidarity people in whatever town it was, wonderful people who all wanted to talk, and I would talk to them and then go to the next town. It was like that. I didn’t care about all the cigarettes I was smoking, and I didn’t care about my reputation as a poet. What I cared about was to prevent the United States from intervening militarily in Central America. We realized that the United States was going to intervene unless there was strong US domestic opposition.

In those years, the Sanctuary Movement was created, and also Witness for Peace and politically organized networks such as CISPES. I was careful not to affiliate with any one particular group or network. Some of these groups were infiltrated by FBI and so on. Leonel had cautioned me about this. He said, “Stay independent. You’re a poet. You were there. You don’t belong to anything. You’re a poet.” I remember the first time there was a very large audience. It was in an auditorium I think in New York City, and I was scared to see hundreds and hundreds of people. I prayed to Monsignor Romero to help me know what to say. “Help,” I said. “I can read poems but I can’t speak extemporaneously.” I couldn’t do that then. I had to develop the ability to do that. And all of a sudden I got to the stage, and I recited the poems and then the question-and-answer session began and somehow it was okay. I could talk. Monsignor Romero helped, I think.

deNiord: He was gone.

Forché: He was dead. But he was still around. I feel his presence. And he has helped me a number of times. So I was able to do this, but I had to contend with the poetry world. And that was another matter altogether. There were very supportive people. But I was also controversial. I have a whole collection of published attacks that Leonel eventually read and was astonished by. “I had no idea,” he said. He didn’t think this kind of thing would happen.

deNiord: Welcome to America.

Forché: I gave these published reviews and essays to Leonel when he visited me. “Here, read them. This is what they think.” I had to come to terms with what this meant. All right. What does it mean to be a political poet? I wondered how the poets of the twentieth century around the world responded to contemporary events that were collectively tormenting, challenging, or horrifying. Wars, military occupation, imprisonment. I began a much more intensive reading of works in translation, and I shared them with my students.

What does it mean to be a political poet? I wondered how the poets of the twentieth century around the world responded to contemporary events that were collectively tormenting, challenging, or horrifying.

deNiord: So two contrary things happened. The book was very popular and became a best-seller. A lot of people who didn’t read poetry read it. But at the same time, the American readers didn’t really know how to respond to it.

Forché: Well, they responded variously but pretty much fell into two camps: those who celebrated it, not because of poetry, but because they were happy that this subject was being addressed, and then there was the camp that felt quite large to me, I don’t know if it was, but that condemned my work—variously condemned it for many reasons. Some people doubted the whole thing had happened, some people thought it was political, some people thought I was a Communist, which is ironic, as I’m a descendent of Czechoslovaks from a country that suffered very much under Communist rule.

deNiord: Some people accused you of being disingenuously liberal.

Forché: Or being a cultural tourist. Some ascribed to me either cunning foresight in terms of career building or they accused me of disingenuousness. My motives and my reasons for doing this and my motives for writing about it were brought into question. You know I went to graduate school at Bowling Green. I didn’t go to Iowa. I didn’t know a lot of other poets. I knew a few. I knew poets of the older generation more than I knew my contemporaries at that time. And they didn’t know me so it would be easy to think—

deNiord: There were cruel reviews.

Forché: Yes.

deNiord: Eliot Weinberger’s is perhaps the worst.

Forché: Yes, that was painful because he even critiqued the way I looked too. Hah! But he reconsidered his views. Eliot later changed his mind.

deNiord: Did he?

Forché: Yes. In an interview, he retracted those earlier critiques. I got to know him later. We haven’t talked in a couple of years, but we settled in a good place. But all this left me wondering about other poets who had experienced such things. What did they do? What did the other poets do? I was making photocopies of poetry by Russians, Greeks, Chileans, Poles, and sharing these with my students, and what I really wanted was an anthology that I could adopt for the classroom, without photocopying so much. The copied packet got to be so thick. But such an anthology didn’t exist at the time.

deNiord: To be criticized by the FBI and your fellow poets must have been trying, to say the least. But such criticism reminds me of the prophet’s plight.

Forché: The government interference was subtle but palpable. I knew about it because of the disinformation campaign. Much later, Robert Parry, founder of Consortium News, spoke with me briefly at a dinner held in honor of Oliver Stone. Robert turned to me and said, “That must have been hard for you in those years.” He confirmed that a special agency had been created within the intelligence community to deal with those of us who seemed to be “in the way” of US policy. I don’t know how much of what the literary world thought came from that disinformation campaign. One of the things they were doing was bringing into question the veracity of the reports on atrocities committed by the armed forces. For example, they denied for years there had been a massacre in El Mozote. We have boxes with photographs from that massacre in our house. A decade passed before there was finally, in 1993, a story in the New Yorker written by Mark Danner proving that it had taken place. Until then, journalists’ careers were in jeopardy because they were accused of having invented these incidents, based on propaganda from the FMLN—that somehow these journalists had been “duped.” That was their word. We were all called “unwitting dupes of international communism.”

I was at a gathering in New York around that time, a book party for someone, and I don’t remember whose party it was, but someone came up to me at that party and said, “Oh, I heard you had become a communist.” And I said, “Who did you hear that from?” The person couldn’t remember. I didn’t know then about the special intelligence group. Years later, I learned that there were about forty people on a list, which had supposedly been drawn up, inexplicably, by then-Secretary of the Interior James Watt, who famously also divided our citizenry into “liberals and Americans.” Some of the literary attacks probably came simply from pique or feelings of jealousy—I’m not very sure here, but some of the attacks might have had other sources. Sometimes I wonder whether some of them had their sources in that disinformation campaign. I just don’t know.

deNiord: This was also a time when John Lennon was on a list, along with many other cultural icons.

Forché: Yes, but I wouldn’t have thought I would be. I wouldn’t have imagined that I was important enough to be surveilled. If you are traveling all over the country, talking against the policy, that is—I was naïve enough not to imagine that that had come to anyone’s attention. However, all those networks—the Sanctuary Movement and Witness for Peace—they were all being watched, we now know, by the FBI. So all of those gatherings and those wonderful living rooms with black beans and tortillas— Everyone always served me black beans and tortillas because they thought that would make me feel really at home. No one imagined that I might be tired of tortillas and black beans. It was difficult, I was alone, and Leonel was still in El Salvador, still under threat. Margarita was still there, Monsignor was dead, some of the nuns were dead. I didn’t trust anybody, really, in the world of organized political opposition in the US because I didn’t know who was who, nor did I want to become the mouthpiece of anyone else. I had the poetry world to contend with—I was hurt by the attacks, but I thought no, this is just something I had to bear. I said to myself: you’re not important. You don’t have to worry. Just do the work.

And already there was another river joined with the river of the El Salvador experience. It was the river of reading continental philosophy. And getting invited to give a paper on Shelley at the University of Maine in Orono by the Romanticist scholar Tony Brinkley. So I went up and talked about Shelley, and Tony introduced me to a professor who’s now at Purdue University, Sandor Goodhart, who does work on the sacrificial and also rabbinical scholarship. These men were all involved in the International Association for Philosophy & Literature, and because I had been close friends with Terrence Des Pres, I had been reading and thinking about the Holocaust for some years already. All this was central to the thinking about witness.

Together, these scholars inspired me to conceive of witness as an impress of extremity, legible in language, as another dimension of reading poetry and literary art emerging in the aftermath of extreme experience, and to formulate the thought of witness.

I began participating on panels with Geoffrey Hartman and others. We visited Professor Hartman’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale. Together, these scholars inspired me to conceive of witness as an impress of extremity, legible in language, as another dimension of reading poetry and literary art emerging in the aftermath of extreme experience, and to formulate the thought of witness. The documents that we read were works of poets making transformative literary art, but what we were discovering was the legibility of extremity within the imagery, within the language, an impress apparent in fragmentation, instances of parataxis, all of that. I thought this a deeper way of talking about what occurs in the realm of the social, between the violence of the state and the institutions of the hearth and intimate, personal life. I think North American poets have been very accustomed to writing out of the intimate life, the personal life. There has been a great mastery of that realm in poetic art. For various reasons, perhaps having to do with the thirties, with the Agrarians and their formulation of close reading, the particular formulation of their poetic thought, but also in response to the political crisis of the thirties, there has been an unspoken proscription against subjects having to do with politics, political involvement, and contemporary events in poetry and literary art. The poets of that movement were, in fact, conservatives.

The origins of this proscription, this reticence, weren’t available to us, who came of age in the sixties, seventies, and eighties. We just felt it. We had assimilated this knowledge that there were things that we shouldn’t write about, and they were left, perhaps unconsciously, out of our work. Hayden Carruth wrote of this, claiming that if one were to read the poetry of the fifties and sixties, one might marvel at the lack of mention of the Cold War or the threat of thermonuclear war. I heard the poet Galway Kinnell make this same observation at Bread Loaf. No mention of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It wasn’t that these men were condemning poets for not writing about these events, they were simply noticing the absence. A few poets, such as Galway Kinnell and Denise Levertov, and other lesser-known poets, wrote against the Vietnam War, but these poems were criticized for their subject matter, and the poets were thought to have succumbed to extraliterary pressures. I became fascinated with this aversion because I was trying to reverse—what do you call it? when you’re trying to reverse-engineer?—I was reverse-engineering the thinking that surrounded me, and that dominated literary culture. I was trying to read those poems not as attacks that were harmful to the republic but as manifestations of a different, perhaps oppositional sensibility.

deNiord: That’s a very Buddhist move on your part.

Forché: Well, there was really no other way. Cry? Drink?

You want to write genuine poetry, arising from the deepest well of your being, and to endure and work imaginatively and freshly in the language, with meditative attention to all that poetry entails, having to do with the structure of thought, the disclosure of mind, the music of the language, the resonances of the words, the etymological origins of the diction, all kinds of play.

deNiord: But it turns into a powerful response on your part.

Forché: We have to think about what has happened to us that we are wary in this way. I think there’s legitimacy to some of the wariness. You want to write genuine poetry, arising from the deepest well of your being, and to endure and work imaginatively and freshly in the language, with meditative attention to all that poetry entails, having to do with the structure of thought, the disclosure of mind, the music of the language, the resonances of the words, the etymological origins of the diction, all kinds of play, you want all that to be there, and it variously is there in the poetry that’s being written now in the United States and elsewhere. But you want all of that. Poetry of Witness is not meant to be a prescription. It wasn’t meant to suggest that we all start writing in response to extremity, nor is “witness” a euphemism for “political” poetry. But this thinking dovetailed with how we think about other forces bearing down on literary culture at that time, such as the importation of European deconstructivism to the United States, where it became the thought of deconstruction.

deNiord: Through the ex-Nazi, Paul de Man.

Forché: That’s right, de Man, and also Heidegger—that calling into question of human subjectivity, of authorship, of logocentrism and the arbitrariness of the sign. Jacques Derrida famously announced at a conference on structuralism at Johns Hopkins in 1966 that we are now in a “poststructuralist” era. When I began reading deconstructionists, I wondered what this thought meant for literature written by Holocaust survivors. Does this thought also sever the connection between language and “unrepresentable experience”? Is all language play? Derrida, fortunately, eventually made his “ethical turn.” This turn came from Emmanuel Levinas, and through his thinking, I began to think through the relation of experience to language. Levinas affected me the most, particularly his notion of our “infinite and inexhaustible obligation to the other.” This I carried over even to the “otherness” of the text.

deNiord: You have a wonderful line in one of your poems, “We are one in the other,” from “Refuge.”

Forché: I had been immersed in reading Holocaust testimony and literature and history since I was a child, for a reason I have absolutely no idea about. The threads were the Holocaust, the Shoah, and resistance to deconstruction until the ethical turn. There was the work with Hartman and Brinkley and Goodhart. It was Geoffrey Hartman who suggested that I couldn’t possibly impose a schema on the poetry of witness and may as well arrange it in historical, chronological order. And then I happened to teach for one semester at the University of Minnesota in 1988, I think, and there I met Vlad Godzich and Jochen Schulte-Sasse, editors of a series on theory and philosophy at the University of Minnesota Press. They guided my reading too. I was immersed then in the Frankfurt School, Adorno, Horkheimer, and Benjamin. I was working on my third book of poems, The Angel of History. The title, of course, comes from Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (part 9). All this fed into thinking about witness.

deNiord: Right.

Forché: These things all converged, along with the practical political education, or the education in the world given by Leonel in Salvador. And the poets who resisted The Country Between Us gave me the opportunity to investigate the ambient thought of my time in literary art. So I’m really actually grateful to them. Each helped me to think about it in a different way, and also to consider what had happened to all of us in our education and formation. What happened in the twentieth century that we arrive at this idea of art as apolitical? Why did we adopt this early nineteenth-century French idea, l’art pour l’art? As you know, Chard, North American poets are always being accused of solipsism by poets in other countries. They say that North American poets write only about themselves. This is the received wisdom or conventional idea about North American poets, but I don’t think it is really true any longer, if it ever was. When I give readings in other countries and talk to poets, however, I find that this impression persists.

What happened in the twentieth century that we arrive at this idea of art as apolitical? Why did we adopt this early nineteenth-century French idea, l’art pour l’art?

* *

deNiord: So you did something in Against Forgetting that Robert Bly never actually did, although he aspired to do it.

Forché: That’s interesting, what do you mean?

deNiord: Well, if you go back to Bly’s magazine The Fifties and The Sixties, he wrote incessantly about the importance of “letting the dogs in,” of the importance of publishing a lot of the same poets that you’ve published.

Forché: There are quite a few that I think Bly was originally involved in translating. Those men, those poet-translators—Robert Bly, W. S. Merwin, James Wright, Strand. Simic—they were all translating.

deNiord: That’s right, they were all translating poets like Trakl, Neruda, Jiménez, Lorca, Machado . . .

Forché: The Swedes.

deNiord: Yes, Tomas Tranströmer especially. But Bly never put an anthology together as exhaustive and meticulous as your two anthologies.

Forché: Well, you know, there was the anthology Another Republic that Charles Simic and Mark Strand collaborated on and published.

deNiord: Oh, yes. A magnificent anthology that begins with Ponge’s work. Still too little known.

Forché: I loved that anthology.

deNiord: I used it all the time.

Forché: When I was trying to introduce students to works in translation that were available, that may have been the only international anthology in print.

deNiord: I wonder if it’s still in print. It should be on the reading list of every MFA student in the country.

Forché: No. It’s no longer in print. It’s a gorgeous anthology. For me, the work began with an idea of creating a new space for poetry that’s engaged with the world and written in the aftermath of extremity, and this became joined to an impulse to bring works in translation together in a substantial collection.

deNiord: You added a whole other dimension to works in translation.

Forché: But there are people missing from that collection only because they did not live through those things. You could make another whole anthology, brilliant works in translation, of poets who don’t fit these particular categories, who can’t be read in light of—

deNiord: And that still needs to be—

Forché: It needs to happen. Ilya Kaminsky did a world translation anthology with Susan Harris.

deNiord: The Ecco Anthology of International Poetry.

Forché: Yes. And there’ve been different efforts here and there. But in the United States it’s difficult to do very much . . .

deNiord: J. D. McClatchy also edited an anthology of contemporary international poetry that Viking published.

Forché: Yes. But our isolation, our geographic isolation, linguistic isolation, is profound. Many of us travel, and many of us study other languages and also translate. But that’s against the critical mass of those who don’t. The US is isolated in a way that Canada, which is part of a commonwealth, is not, and Mexico, which looks toward Latin America and the Caribbean, is not.

deNiord: And how that isolation redounds on particular types of poetry. I think, you know, The Country Between Us just ran head-on into a resistance that . . .

Forché: I wasn’t ready for.

deNiord: . . . that challenged all sorts of archaic notions of American patriotism and patriarchal shibboleths, perhaps most notably the conventional notion of a woman’s place in society. But the question that loops through the American male psyche, even still, asks, What can an American woman know, especially a young American woman, about the male business of American foreign policy?

Forché: Well, I did receive support from some people, however. Susan Sontag, for example, said, “Keep going, keep writing.” Her advice was: “Write well, that’s the best revenge.” That’s what she used to say. And Hans Magnus Enzensberger was also supportive. And Jacobo Timerman and Luisa Valenzuela and Charlie Simic, too, all had encouraging words for me.

deNiord: It must’ve been also—you must’ve had some support from a few like-minded women like Adrienne Rich?

Forché: I don’t think I was viewed as a feminist. I was raised by a feminist mother, but it seemed I didn’t write explicitly feminist poems. Many of my poems were written, however, about women, and especially in Gathering the Tribes, but I was never considered one of the feminist poets. Honor Moore compiled a very good anthology of second-wave feminist poets for the New American Library, and she included me, but I’m not usually included in the history of that movement. I wasn’t read as a feminist. Depending on your affiliations, you can get very narrowly defined in the United States. I’m read as a human rights person, but not—

deNiord: Somewhere you said that you write for community. Stanley Kunitz also makes a big point about this, in his introduction to Gathering the Tribes, that you enjoy writing for a community of readers and poets.

Forché: Well, I don’t write for the drawer, although there’s a lot of work in the drawer because I don’t enjoy publishing. A lot of people enjoy it. I think it’s horrible. It’s a very challenging experience. I don’t want to be misunderstood, because I do sympathize with the longing people have for their work to have a life in the world, to be read by others, and I understand the challenges now of having that come to fruition. I’m not ungrateful for all the opportunities I’ve had. But partly because of the attacks and especially because after every book that’s published there’s this period when I can’t write, I try to postpone publishing as long as I can. I can think I have this strength of spirit to take what comes, but it’s not an easy world. I don’t at the moment have an American publisher. I have a wonderful British publisher, Bloodaxe, Neil Astley’s press. He writes, “Can I put it [In the Lateness of the World] on the list for this season? Can I put it on the list?” I just said no again. I said no. I told him it’s not ready yet. And I’m worried about this, but I have to have an American publisher first, I’m told.

deNiord: Well, you’re also publishing a memoir.

Forché: Yes, I have a memoir. Its tentative title is the first line of “The Colonel”: “What You Have Heard Is True.” I’m hoping to finish a draft of it this month.

deNiord: You’re making progress.

Forché: Yes. I’m making progress, but I have been on the road so much that I think that I could have been making a lot more progress. It’s very difficult, reliving those events. Most of this memoir takes place between 1977 and 1983.

deNiord: Has it been helpful? Writing it?

Forché: I think so now, and I’ve been fortunate to be able to share it with people who are still alive. Their support, and their affirmation of my account of that time has helped, but it’s hard to relive it. Many of the people I write about in my memoir are dead. Everything written suggests what has been left out. Everything included announces an absence. The process of writing a work of memoir is very different than poetry. It has partly to do with structure and partly with weight, with holding the whole of it within.

deNiord: You worked for NPR in Lebanon and Beirut, in—

Forché: Yes, for NPR in Beirut in the winter of 1983–84, and I accompanied my husband to South Africa in 1985–86, where I worked as a liaison between parents of detained children and international human rights groups. But we didn’t last long in apartheid South Africa. That’s another story.

deNiord: By the way, it’s so inconceivable to me that you received such critical response from so many poets who were out there protesting the war.

Forché: It probably had something to do with gender, it had something to do with “out of the blue,” you know? They didn’t know me. And also, when you do cross over into a larger audience—and I think Claudia Rankine is getting some of this right now—they say they don’t think that what you have written is poetry. Her book became a best-seller. I think poets should celebrate that and say, “Yes! We’re breaking onto the New York Times best-seller list! If one of us, so maybe then one day the rest of us.” You know, seriously, if someone reads and likes Claudia’s work, then they’re also going to read this one or that other one. I think that’s how it works. But poets feel deprived, they’re isolated. I think males are especially raised in our culture to have expectations of accomplishment and reward, and not only within themselves but from without. Women are not raised to expect that anything will happen. We don’t suffer the disappointment that our brothers do. No one pressures a woman to accomplish something.

deNiord: But when she does . . .

Forché: Well, that’s another matter. Watch out. But the men are pressured.

deNiord: You know that beautiful poem you dedicated to your son in Blue Hour? I wanted to ask you about that because I think it has a lot to do with what I think you’re talking about right now. It’s called “Curfew.”

Forché: Yes, oh God.

deNiord: I’m wondering if you could read it, right here, quickly. And just talk about it a little bit.

Forché:

The curfew was as long as anyone could remember

Certainty’s tent was pulled from its little stakes

It was better not to speak any language

There was a man cloaked in doves, there was chandelier music

The city, translucent, shattered but did not disappear

At the hour between the no longer and the still to come

The child asked if the bones in the wall

Belonged to the lights in the tunnel

Yes, I said, and the stars nailed shut his heaven

I can unpack it if you want.

deNiord: I’m thinking the ending has something to do with that stairway that Terrence Des Pres led you to, behind Notre Dame cathedral.

Forché: The “nailed shut the heaven”?

deNiord: More so “the lights in the tunnel.”

Forché: Oh, yes! You are right, “the lights in the tunnel” belong to the memorial of the deportees dug beneath the Seine in Paris. The bones in the tunnel is an image from the catacombs we lived above in Paris. But they were also an image for the camps that I visited. I spent some time in Poland in 2004 and in Prague before that, during many visits since 1990, just after Václav Havel became president. And those places. So . . .

deNiord: Terezín? Did you go to Terezín too?

Forché: Yes, I’ll tell you about that. I went to Terezín before the bussing of tourists began there.

deNiord: I remember reading about that.

Forché: One day, Daniel Simko, the Slovak American poet and my former student, was with me alone all day there. There was one other woman, and I remember oddly that she was shelling peas into a bowl and beside her there were leeks that had just been pulled from a garden and were wrapped in paper.

deNiord: Daniel was the one who babysat for your son, Sean, in Provincetown, and who traveled with you to central Europe?

Forché: Yes. The woman was shelling peas, and she also had a bouquet of calla lilies at her feet. She was sitting in this little hut at the entrance of Theresienstadt. She just waved us in. It was a time before anyone went there much. It wasn’t open at the time, but she seemed not to mind us. We went into the barracks; there was stuff still there that hadn’t been put away: these weird things, booklets and such. And we just walked and walked and walked. We were completely stunned that no one bothered us and no one else came. Now I’m told that there are large busses in a parking lot for group tours. We were just there all day. Alone. I had taken Sean through the catacombs in Paris, along with Rita Dove and her daughter. We thought the kids would enjoy going through these tunnels, six kilometers underground, all completely filled with skeletons and human bones. You must go there sometime. It’s labyrinthine, and you just have to keep marching. When we got halfway through we realized that our kids’ eyes were on stalks. Rita said, “What do you think we should do? Should we go back?” I thought we might as well keep going, we’re halfway. So we just marched them through. And both Sean and Rita’s daughter were very quiet for some time after.

deNiord: But they knew what was going on.

Forché: Well, they knew these were human bones. So I had also taken Sean to the memorial of the deportees, and I had explained to him about the lights—that there was one for each life. And later he actually said to me, “Are the lights for those people the bones? Are they connected?” And I thought: they might as well be. So I said yes. And he just looked at me, and I realized that something had happened inside of him. So that came from the connection between those two places, although they’re not really connected.

deNiord: Right. The idea of “Curfew”?

Forché: The curfew was—what were we doing? Oh! I know what it was. We had a curfew for all the kids. It was a curfew that they couldn’t be outside after a certain hour, but we also talked about living under curfew in Beirut. We talked about it a lot because we got caught one night violating that curfew, my husband and I and some friends. That’s one of the stories that gets told in our house, and Sean wanted to know how long we would have a curfew. Forever, I could answer, because in his young life it would have seemed so. When he came home from the first day of second grade, having finished first grade, he asked, “Mom, how long is this going to go on?” He thought school was over when he finished first grade: I’ve done it, okay, now on to something else. He wanted to know how long I was going to make him come home at a certain hour, and I said, “Never mind, forever.” So one night all these images splashed into the same poem. It isn’t tethered to any single event, it’s not a report. It’s a cluster of images.

deNiord: Well, that’s a hell of a last line. That notion of the stars nailing the heaven shut?

Forché: Thank you.

deNiord: You have that and you have this whole interrogation going on in your work that has to do with the human and the nonhuman and the ways in which they interact. You’re always doing that, you’re leaping into—

Forché: I think that’s true, yes, especially from the child’s point of view.

August 2015

Carolyn Forché’s first volume, Gathering the Tribes, was followed by The Country Between Us, The Angel of History, and Blue Hour. Her latest collection, In the Lateness of the World, is forthcoming. Nelson Mandela praised her international anthology, Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness (1993), as “a blow against tyranny, against prejudice, against injustice.” In 1998 she received the Edita & Ira Morris Hiroshima Foundation for Peace & Culture Award for her human rights advocacy and the preservation of memory and culture. She holds a University Professorship at Georgetown University, where she directs Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice. She is currently at work on a memoir.

Editorial note: For more, read part 2 and part 3 of this interview, plus five of Forché’s previously unpublished poems.