“We Will Not Give Up on Each Other”: A Conversation with Major Jackson

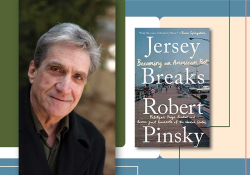

Major Jackson is the author of four collections of poetry, including Roll Deep (2015), which won the 2016 Vermont Book Award and was hailed in the New York Times Book Review as “a remixed Odyssey.” His other volumes include Holding Company (2010), Hoops (2006), and Leaving Saturn (2002), which won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize and was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award. His fifth collection is forthcoming in 2020. Here he discusses with Chard deNiord his early life, influences, and the importance of addressing the moral and ethical questions of the time.

Chard deNiord: You mentioned to me in a previous conversation that you started talking and reading like crazy when you were three years old.

Major Jackson: (Laughs) Right.

deNiord: And that you had a verbal acumen almost from the start that maybe you weren’t aware of as a gift, but looking back now realize was in fact a gift.

Jackson: Some of it, Chard, might be owed to the drama of the black church. My grandmother was a Pentecostal, so that meant we attended church every Sunday and often Wednesday nights, and it was difficult, especially at a young age, to ignore the immense swelter of emotion that occurs in such a space. I vividly recall being struck by the—I say now—high drama of the pastor, as we say, tending to the flock in these deeply emotive tones and whose use of language was ritualistic and urgent and celebratory.

In contrast, or rather concurrently, reading was an activity in my home that invited silence and quiet; I was drawn, quite early as a child, to that sense of contemplativeness, that space of deep engagement reading often provokes. Both spoke to the core and structure of my spirit and being-in-the-world. Not that we were particularly a literary family or household, but as a kid, I would more likely gravitate to books than go outside. As a result, as a teenager, for better or for worse, I never truly parsed out the different functions language served. Use of language was ritualistic to my ears, and like the church, books created environments, sacred spaces to cultivate an inner life. And probably given some of the events that would occur later in my life, probably the activity that saved me because reading became a kind of refuge away from the hurt and early disappointments.

Some friends and I recently reminisced about how applying for and procuring your first library card was as important as obtaining one’s driving license; the same kind of joy and sense of freedom that’s attendant with getting on the road was what we felt in formally joining the world of ideas that a library card symbolized.

And, again, I was more likely to go to the library in my neighborhood after school rather than home or the baseball field. Sports came later when some elementary school friends showed up on my doorstep with an extra jersey, a baseball cap, and glove because they needed a ninth person to play on their team with the Police Athletic League. So I pitched and played shortstop between the ages of twelve to fifteen.

Applying for and procuring your first library card was as important as obtaining one’s driving license; the same kind of joy and sense of freedom that’s attendant with getting on the road was what we felt in formally joining the world of ideas that a library card symbolized.

deNiord: This was where?

Jackson: In North Philadelphia. And so sports entered my life, thankfully. Otherwise, my addiction to books, of communing with other people’s thoughts, might have led to a life squandered, say as a medieval historian, stuck in the basement of some private library or, you know, some archive.

deNiord: What did you recognize it as? Were you drawn to stories specifically and did you see language as a kind of ticket out of North Philadelphia?

Jackson: No. I did not feel like I needed to escape out of my immediate surroundings, but believe it or not, merely the fascination with the incantatory power of words themselves, their singular auras, is what I inherited. My grandmother had this phrase I’ve lately remembered. She would refer to the Bible as the Living Word, which carried in its phrasing the mystical properties members of my community and black people in America came to view language as possessing, a certain kind of potency ascribed to literacy that was forbidden, as you will recall, to enslaved Africans who were not allowed to read and write. Many of the early slave narratives discuss this. Frederick Douglass talks about this—how writing and reading co-sponsor one’s freedom. That’s my foundation, you understand? The stories were important, of course, as well as the sense of transport.

Frederick Douglass talks about this—how writing and reading co-sponsor one’s freedom. That’s my foundation, you understand?

deNiord: Yes.

Jackson: So my family, believe it or not, still carried that same kind of attitude toward language. Later, of course, you come to realize that language can be manipulated, can be abused, but in my household, books were sacred, language was sacred, the Living Word as if language can animate and bring into existence spells—and of course, my grandmother was referring to the Bible, but I transferred that to all texts. There were plenty in the household, and it was as if I could feel their heat when I walked by them.

deNiord: Right.

Jackson: But what did I see in the experience? I would answer in reply: the immersion that happens when you read—that sense of time falling away, entering into another space. I could read for hours, and it would feel, like, you know, a blip in real time, you know? And, of course, as I report elsewhere, I gravitated quickly to poetry. The language was more rhythmic, as if I were genetically encoded to respond to its tensions, promontories, and patterns of sound. This was another way into my intellectual life.

deNiord: Your mother must have been fascinated by your interests, especially at such a young age.

Jackson: I guess so, or not. She and my grandmother frequently purchased used books from church basements, libraries, and flea markets. So, I do not think it was a surprise. Engrossing your child in The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood or the Encyclopedia Brown series is an effective way of keeping a child occupied. Books were my babysitters.

deNiord: So there were two traditions going on here—that of your early reading and the oral tradition of the church.

Jackson: Right.

deNiord: Right? And then the written. So you were getting both.

Jackson: In big doses. (Laughs)

deNiord: And, of course, music went along with this.

Jackson: That’s right.

deNiord: Listening to hymns and singing in church must have been powerful early influences.

Jackson: In a real sense, that truly was my early training. That’s where my ears and sense of cadences were cultivated. Those songs come to me now: “Down by the Riverside,” “It’s Me O Lord,” “Mary Don’t You Weep.” But I want to say, yes, in the church, but even in the language, as I am saying here. I was drawn to the spells of sentences, their properties, how they carried codes, certain kinds of meanings outside of what was literally being uttered. And you know, later, of course, I would see as much operating in writers like Faulkner and Jean Toomer who became my guides of sorts. I feel like there’s something in Toomer’s Cane that bespeaks still even today the South because he, almost hypnotically, entranced himself into the earth and language. We know this because we are entranced, still.

deNiord: Yeah, but silence was also important. You’ve written a lot about the mysticism of silence, and the kind of cognitive dance that goes on in silence.

Jackson: Right.

deNiord: That’s the phrase you use.

Jackson: Well, yeah, I guess when I wrote that, I was thinking about, you know, that space you enter into when you’re reading someone’s work and there’s that frisson of an encounter with language that attends with something that is said authentically and fresh. But you don’t have a full grasp of its meaning, and so living in that space of—and living in that experience of language working on you, even if you do not have a hold on the surface. That’s the silence that I treasure because it’s pushing me toward possibilities of meaning and existence. And, you know, what the author intends and what is conveyed. For some people, the lane is wide. (Laughs)

deNiord: Yes.

Jackson: Right?

deNiord: For some very wide. Galway Kinnell once told me he moved to Sheffield, Vermont, simply because of the silence.

As I’ve gotten older, I appreciate more the width of openness of meanings and possibilities, rather than the narrow pockets and corners of truth.

Jackson: Some people need the author to connect the dots for them, right? As I’ve gotten older, I appreciate more the width of openness of meanings and possibilities, rather than the narrow pockets and corners of truth. (Laughs)

deNiord: I asked my friend, Bruce Smith, who’s also from Philadelphia . . .

Jackson: He’s a great poet, great.

deNiord: I asked him, “If you had one question for Major, what would it be?” He wrote back, “Does formality and attention to form, rhyme, received forms, work with or against innovative new forms that arise out of the African American experience?”

Jackson: That’s a good question. Well, if I think about the formality of a blues poem, say a poem by Langston Hughes, that is, the vernacular tradition from whence it is born—and the blues, itself, is building on—what one might have previously called experiments have kind of solidified into convention. And frankly, more than forms, if I’m writing formally, I’m really using that particular modality or method to reach toward something that is authentic. Sometimes, in a poet’s work, there is the performance of experimentation, or let me say, the performance of innovation in poetry that feels itself overly wrought. I think the risks are attendant in both directions.

For me, I have just enough of a limber attitude toward composing poetry, even with constraints and forms, to know that the quest is not the façade of the building itself I’m after, with all its decorative elements, but the insights that I glean along the way, the interlocking rooms of our imagination that lead to a greater clarity of my existence. I think about Seamus Heaney’s line in that poem, “Personal Helicon,” “I rhyme / To see myself”—the last lines—“I rhyme / To see myself, to set the darkness echoing,” which describes accurately my experience of writing poems, a way of formally making music so that I can arrive at the truths of my life.

So, for some, as Bruce indicates, such formalism works against their general spirit, but for me and the poets that I turn to, that I identify with, who are driven by and addicted to the poem unfolding line by line, coming into being breath by breath, writing with some framework pushes us toward infinite ways of existing and breathing and thinking that define and divine (and some would say, create) the self. Like most readers, I like musical notes that are played in poems that you can hear and recognize (like when Paul Blackburn riffs on Robert Frost “and local stops before I sleep” in “Brooklyn Narcissus”), and so certain sounds in my poems will be identified as emerging from the black experience, a cultural watermark of sorts, then some will sound, and Bruce knows this, as if they come from the haunts and hollers of our shared humanity.

deNiord: You stick to a particularly formal ten-line structure in Holding Company.

Jackson: You know, with those poems in Holding Company, those kind of typify and epitomize my attitude toward writing poetry, which is I always render myself a student of the art. So, really, they were experiments. What can I do within this short frame? What kinds of utterances can emerge from such a tight pocket of sound?

deNiord: Yes, you stuck to it.

Jackson: I believe I wrote ninety or slightly more, and eighty were published in the book. Writing in a ten-line structure with a set number of syllables was a way of getting inside the poem that was, you know, the equivalent of working a patch of land, and patiently sticking with it and seeing what grows there.

deNiord: You said something astute about this in a previous interview: “Writing in tradition and borrowing the accumulated power of that tradition—this type of poet has a contract with the reader as a result of that familiarity. By contrast, the reader of free-verse poems has to make a serious adjustment in realizing the work.” And so I’m wondering if you could talk about what that serious adjustment is. You know, Emerson called it “Meter-making Argument.”

Jackson: Well, when you don’t have a frame of reference when entering a poem—so if I’m playin’ “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and you know the notes, I know the notes, in a very real sense, you and I are both going to know that at some point, the song will require you to sing that high note on “rockets’ red glare.” One of my favorite jazz guitarists, Sonny Sharrock, who was an immense avant-garde artist, for most people played noise, except for when he provided a frame of a song.

So the adjustment is this: I’m bringing to the page how I walk, how I breathe, my freedom, my history, my lineage, family, struggles, my illnesses, ailments, my joys, my triumphs—all of which you don’t know on the surface when you first meet me, when you encounter me, say at a garden party or while waiting in a lobby during intermission at some show. And so the poem becomes a way of opening a door into a self, but if you’re not familiar with someone who grows up, in let’s say, Xichang, China, right? or know their food or their rituals, right? there’s that period where you have to become acquainted in order to fully appreciate their journey and the substance of their being. I think the poem, especially a poem in which no cultural or intellectual or philosophic or aesthetic tradition grounds the reader’s experience, that poem has a lot of pressure to acquaint a reader with what is unfamiliar.

Now, what’s great is—what works for both of us is that there is a limited number of human experiences that make up our journey on earth, that’s finite, right? We were born to parents, or we’re adopted, we enter into a community. That community has its rituals around food and culture and religion and so on. We die, we experience loss, and we fall in love. That’s what we have going for us. And so how I play those particular notes is what’s going to be the bridge for the reader into the poem; here I’m talking about a soundscape or surface of the poem; others might refer to it as form.

But the particularities—that’s where I get to have fun. (Laughs) Because I need you to see North Philadelphia mid-1970s, early 1980s, as hip-hop is emerging as an important force in youth across the country, as Reagan’s trickle-down economics policy is dismantling whole communities, as the crack epidemic is taking hold, a real plague, a social illness. I mean, I have to do that work and hopefully create a portrait of empathy rather than playing into, playing into received messages of social pathology in black, urban communities or whatever was said about the communities of brown people in America at that time. So, early on, I turned to poetic form because readers could begin vaguely to see and hear the humanity of those they could not imagine.

deNiord: Plus you’d already been hearing it in church and in your blood by that point.

Jackson: This semester at the University of Vermont I taught a course called “Resistance and Humanity in African American Literature, Visual Arts and Performance.” It was pretty much a survey course of twentieth-century and early twenty-first-century art—Afro-Futurist, Afro-Surrealist, Afro-Pessimist—and what occurred to me was the number of artists who leaned into the spirituals: James Weldon Johnson through Alvin Ailey, a number of black artists. That is their foundation, and that music, borne out of that particular period when I was younger in church. Within the context of the church, it was powerful to hear those songs. Because they were so full of encoded cellular, prehensile messages.

deNiord: Good way to put it.

Jackson: Of how to survive, how to exist. I was delighted to be reminded of the importance of that. Because that’s a form that is part of our DNA. Just thinking of how the blues built off of those early spirituals. And how R&B comes from that. You know, you can just keep going. Rock and roll comes from it, which means the nation self-renews through its music, and heals, and at the core of its soul is the suffering of black folk.

deNiord: You could—such a mecca for R&B, rock and roll, soul, and folk music.

Jackson: But to some today, the spirit of the spirituals sounds too ancient, much like eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ballads or sonnets. But it is a crucial component of our literary tradition. And then, going back to Bruce’s question—we can still build off of that power if we are innovative in how we utilize the essential elements of form.

deNiord: I’m fascinated by your love for music, specifically hip-hop, from early on.

Jackson: Which I know very little today as a fifty-year-old man.

deNiord: At some point in your twenties you discovered Sun Ra, right? He turned out to be a huge influence.

Jackson: My grandfather didn’t have Sun Ra’s recordings, but he did have some old 78s, a lot of big-band stuff in the house. Then sometime after Coltrane, he stopped listening. Sun Ra did play big bands, but Sun Ra went far out, more experimental, in the early 1960s, part of the “new thing” in jazz. So I didn’t discover Sun Ra until later while living in Germantown in Philadelphia with my mom and stepfather. We were about two blocks away from Sun Ra’s house, so to bike in the neighborhood was to hear the band practicing. But I didn’t know who they were as a kid.

Later, when I worked at the Painted Bride Arts Center, where Sun Ra would perform New Year’s Eve concerts—and again, what was familiar was the theatrical elements of Sun Ra’s performances that took me back to the church. He also valued dissonance, and intellectually at the time I was starting to appreciate dissonance as protest, particularly vis-à-vis Coltrane, whose horn felt as though it was articulating the rage of the 1960s, frustrations of the civil rights movement and the black freedom struggle, which I began to embrace while in college.

Intellectually at the time I was starting to appreciate dissonance as protest, particularly vis-à-vis Coltrane, whose horn felt as though it was articulating the rage of the 1960s, frustrations of the civil rights movement and the black freedom struggle, which I began to embrace while in college.

deNiord: But also this belief that this music and message and legacy were coming from somewhere else. It was coming from outer space.

Jackson: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

deNiord: Sun Ra, right?

Jackson: He and his band are an important pillar of Afro-Futurism.

deNiord: Saturn, right.

Jackson: Hence the title of my first book, Leaving Saturn.

deNiord: Yes.

There’s something about the conversations that happen in music that we as poets can only aspire to. Words do have their limitations.

Jackson: You know what is interesting, several other artists also sing about Saturn—listen to Stevie Wonder, whose birthday was yesterday. On the album Songs in the Key of Life, you can hear him postulate similar notions about black identity and origins on a song titled “Saturn.” I’m curious to know if he was paying attention to Sun Ra. Their music is transcendent and hits in the way that language cannot. There’s something about the conversations that happen in music that we as poets can only aspire to. Words do have their limitations.

deNiord: As far as the music—

Jackson: As far as the music, and the conversations. Because the conversations feel more exploratory, more reaching, even classical music, reaching for a realm of transcendence that feels beyond our reality today.

deNiord: Keats’s “Nightingale.”

Jackson: Yeah, yeah. That’s right. Or any of the Romantics, for which transcendence is facilitated through language by way of the imagination.

deNiord: Of that sound.

Jackson: Yeah.

deNiord: I’d like to come back to that, but I’m fascinated by the divide that you see in society in general, particularly in colleges. My students listen to rap constantly and yet they have no conversations with their black peers. There’s a kind of social schizophrenia on campuses in which white students are obsessed with rap and hip-hop artists and yet they interact with very few if any of the African American students on campus. You must see this at UVM.

Jackson: Amiri Baraka has a line in one of his poems where he says, “Love black music, hate black people.” The duality and the irony of that. And that’s always been the case, hasn’t it?

I have not read much on this subject, save for Norman Mailer’s problematic “The White Negro,” but others have articulated how the music comes in to fill a void, a space of need, and then that need also might be associated with reconciling history. Like, it’s easier to absorb the music than to absorb the people and embrace the people. You know, it’s a way of reconciling a consciousness around the history and treatment of brown and black people, even still today.

Part of the impetus of that class that I taught was to say, “Hey, you know, what you are consuming, the narratives that you consume in the novels, the books, the art, yes, it’s about resistance, but it’s also about everyday people who experience joy, who do not have to be a problem in your sociology class, or you don’t have to look at black folk as very simply an oppressed people.” There’s a level of resilience and a level of joy inherent that is instructive about survival in the face of an existential reality for blacks whose lives have never mattered in the United States, or whose humanity and worth have waxed and waned. The hope is that the music and the art humanizes in a way that might lead toward and allow for conversation. That, hopefully, in many cases leads to a deeper exchange and empathy for black folk.

The hope is that the music and the art humanizes in a way that might lead toward and allow for conversation. That, hopefully, in many cases leads to a deeper exchange and empathy for black folk.

deNiord: And yet, even though those conversations might take place on the street or with friends, you write powerfully in your wonderful essay, “A Mystifying Silence: Big and Black,” that it’s “the dearth of poems written by white people that address racial issues, that chronicle our struggle as a democracy to find tranquility and harmony as a nation containing many nations.” You wrote that in 2007. I wonder if you feel as if anything’s changed.

Jackson: I think it has. Not to the heights that I wish, but I do feel as though that essay hit at a moment in which we were as a nation grappling yet again—that was 2007, a year before Obama was elected—so it was during the campaign season, right? So a year before Obama, our first black president was elected in the US. We were also in the wake of Fred Viebahn’s letter to the Academy of American Poets, charging them with a certain kind of elitism. That was eleven years after Cave Canem was founded. We were at a very crucial moment in our history in which we realized that if we were going to go forward as a unified nation, as a people, then all hands on deck with the best minds of our generation . . .

deNiord: Have been destroyed by madness?

Jackson: Have not been destroyed by madness.

And can lend their voice, can lend their intellect to these issues, then we all are in a better position to exercise our freedoms. And that’s what it’s all about for me.

Even the most apolitical poem can achieve that kind of force, can articulate and voice our sacred and profound sovereignty as human beings.

But if we’re all either looking down and writing about the grass beneath our feet, if we’re all looking up to the stars, seeking an alternative narrative of our existence or the transcendent, or worse, in solipsistic fashion, amplifying our personal narratives into myth, then we’re not engaging with each other. In that essay, I was urging us to treat one another as the vital material of poetry.

The fact is politicians make decisions that impact the lives of the most vulnerable, the marginalized peoples among us, of all ethnicities, including the poor whites who are, once again, being manipulated by political rhetoric. If the poetry we write genuinely addresses these issues and bears witness, then we have a fuller picture, and I think for us to only rely on black folk or Latinos or Asians (in short, the visible Others) to write about race, that historical trap and sinkhole which regrettably binds us and needs to be theoretically dismantled if we are to heal, if white poets do not contemplate and begin to reveal how they write and publish out of a tradition of privilege, how they partake and profit from whiteness, which is the long, manipulated story of this nation, whether we’re talking about the immigrant from Europe who becomes white upon arrival to these shores or the overly mythologized WASP-ish narratives of Mayflower whiteness, then we will begin to fill what I consider to be spiritually empty about our self-mythologizing with authentic and fuller accounts of a country that believes in the sanctity and worth of each person.

My point was that white folk need to address these issues—and I do not mean very simply outing their racist grandfather or grandmother, but genuinely, how does “race” profit you and feed you as an artist, you know?

deNiord: I’d like to read a passage from Russell Banks’s novel Cloudsplitter that redounds profoundly to what you’ve just said.

Jackson: Yes, please.

deNiord: It’s powerful. This is where John Brown’s son is telling the story about his father: “Father did not wish to address or hear from anyone else. He wanted no Garrisonians, no anti-slavery socialites, no white people at all. Let the whites make their own policy as they always have. We must have our own.” He’s saying that about himself, John Brown. Then he goes on to say, “In a thoroughly racialized society, it was a strange kind of loneliness and perhaps a peculiarly American one to feel cut off from your own race, but in those agonizing years before the war, for a small number of us, that’s what it had come to. This matter of difference and sameness, the way in which we were different from the Negroes and the same as the whites, and vice versa, the ways in which we were the same as the Negroes and different from the whites, was a vexing one. If a white person persists as we did in delineating and defining these areas, soon he will find himself uncomfortable with people of both races, with the one because of his unwanted knowledge of their deepest loyalties and prejudices, for a fellow white. Privy to their race conversations and adept at decoding those closed tribal communiqués, he understands their true motives and basic attributes all too well. And I’m comfortable with the other also because whenever he chooses to allow it, his pale skin will keep him safe from their predators.”

Jackson: That’s enormously powerful. Yeah. As you were reading, I was thinking about the limitations of MFA programs, of which there are many, but one stands out now listening to that: we do not teach in MFA programs as part of a writer’s evolution, what does it mean to spiritually evolve and grow inside one’s practice of writing poetry or fiction or essays? Maybe because I did have mentors like Sonia Sanchez and Garrett Hongo, early on I realized our words have immense utility outside of our own paltry desire to express ourselves. Right? I’m not being prescriptive here, but there’s a responsibility attendant with being a writer, one whose voice is heard above others because of the enormous platform; it’s almost an imperative to address the moral and ethical questions of one’s time.

There’s a responsibility attendant with being a writer, one whose voice is heard above others because of the enormous platform; it’s almost an imperative to address the moral and ethical questions of one’s time.

deNiord: Nicely put.

Jackson: No one could have told me that when I was younger.

deNiord: Yeah.

Jackson: I mean, I saw models of it. I mean, Philip Levine was one such model and Sharon Olds and Muriel Rukeyser. Gwendolyn Brooks and Sonia Sanchez and Amiri Baraka. I had many.

deNiord: And Etheridge Knight also?

Jackson: Yes! Etheridge, who I invoke in my introduction to Best American Poetry. I allude to Etheridge’s formulation of that sacred relationship: the poem, the poet, and the people, and how the poem mediates human relations, one of the ancient functions of griots and bards. Of course, no one is born, then someone puts a cloak on their shoulders and officially proclaims, “You’re a bard” or “You’re a griot.” One has to evolve into their “awarenesses”—and I truly believe this— this is how the poems write us into a consciousness that either serves the community or continues to serve our own mythology.

I have a friend who tells a story about giving a reading in Montpelier, and then afterward how we went to a bar. He’s really anxious to hear what I have to say about the poems. I wasn’t immediately forthcoming. After the second beer, he finally asks, “So, what do you think of the new work?” and with faux enthusiasm, I state: “Yeah, they’re good. You’re good.” He knew I wasn’t earnest in that moment. We are long friends and I love him and felt obligated to be honest, knowing our relationship could grow in that moment and withstand the tough questions. I asked: “When are you going to stop being the hero in your own poems?”

deNiord: You said this?

Jackson: I probably had one too many at that point. But—

deNiord: But you knew to say it, maybe.

Jackson: He said for a whole year, he was debilitated.

deNiord: After that?

Jackson: By that question. Like, he couldn’t write. He said the question daunted him to contemplate the relationship between the art . . .

deNiord: And himself?

Jackson: Yeah. And how the poem amplifies the id.

deNiord: That was frank.

Jackson: Or is the poem going to do other kinds of work? And it’s been there all along for me. I mean, in terms of the poems I gravitated toward and the poets whose eloquent work consoled my restlessness and anxieties about existence—secular consolations. And even in their most personal moments, it seemed like the poems were gifting me something else than just a window into the poet’s life.

deNiord: When do you think you realized that? There must have been a moment.

Jackson: After, I would say—well, I was reading so much of Levine early on—in graduate school. That’s why I’m mentioning it. I see his name—all these people were influential in some form. James Wright came later. But definitely Lucille Clifton. So those examples were there. And, again, this isn’t necessarily advocacy for an aesthetics of witness or the political poem. I’m not urging us toward that, but I’m just saying it’s one of the important growth areas that happens in a poet’s journey, when one realizes the reach and impact of one’s words, and the enormous responsibility of being, as Auden put it, “a way of happening, a mouth.”

deNiord: It reminds me very much of what Leonel Gómez told Carolyn Forché when she was a young poet. She was teaching at San Diego State University, and Gómez, a cousin of her mentor, the poet Claribel Alegría, just shows up on her doorstep one day and says: “You have to go to El Salvador.” She replied, “I’ve got poems to write. I’m a teacher. I can’t just leave my job.” And Gómez says, “What are you going do for the rest of your life? Write poems about yourself?”

Jackson: Right. (Laughs)

deNiord: So she said, “You know? I better go to El Salvador.”

Jackson: That’s right. (Laughs) You know, I will say this. Two things I’ll say: I know that moment. I just heard her read from her memoir where she discusses that encounter, a wonderful story. It occurred to me that I, too, had people in my life who urged me into meaningful song. Father Dave Hagan, who taught math in sixth grade at St. Elizabeth’s, who was also my basketball coach. Not that he was not a committed teacher or coach, but both were truly arenas that allowed him to proselytize Christian ideals of universal harmony and our role in helping to achieve as much. He was a bit of a grouch, but his lessons were quite tender. Father Dave Hagan was the first person to utter the word “humanitarian” to me, which became an aspirational goal of my life.

I, too, had people in my life who urged me into meaningful song. Father Dave Hagan was the first person to utter the word “humanitarian” to me, which became an aspirational goal of my life.

deNiord: A priest.

Jackson: He was also associated with the Berrigan brothers, Daniel and Philip Berrigan, the antiwar priests . . .

deNiord: And Catholic Workers.

Jackson: That’s right. So, those folks. The second beckoning into my sense of responsibility occurred when Sonia Sanchez invited me to join her, as an undergraduate student in her class at Temple University, for a reading at Bard. She said, I often bring students with me to open up readings with a poem of their own. On the stage was an elderly man in a wheelchair, the great writer Chinua Achebe.

deNiord: Oh, my.

Jackson: I was privileged to simply listen to them in his living room later that evening discuss postcolonial writers, their relationship to the black freedom struggle, a magazine I had not yet encountered but sought when I returned to campus, Présence Africaine. Sitting at their feet, literally, and reveling in their long friendship was both a privilege and calling. Although not his student, I also had conversations with Michael Harper, all before I was published, all before my first book. So, in a way, I was cultivated through my reading and associations into viewing writing as more than “personal expression.” Michael Harper says in an interview, we have to “enter into a continuum of consciousness.” And that phrase, that entering into a continuum, is what I realize my work has sought to accomplish all along.

Michael Harper says in an interview, we have to “enter into a continuum of consciousness.” And that phrase, that entering into a continuum, is what I realize my work has sought to accomplish all along.

deNiord: He also said, “The heartbeat is history.”

Jackson: Yes. And Derek Walcott says, “The sea is history.” What an echo. The sea and the heart are history. Yeah, that continuum of consciousness and that awareness is a—

deNiord: I’m struck by something T. R. Hummer said in his blurb for one of your books; that your poems “always keep their cool, and then swerve from the ordinary to the miraculous and beyond.”

Jackson: Really very generous and kind.

deNiord: That’s true. Can you mention what a few of those “beyonds” are? “Beyond the miraculous.”

Jackson: We come from different parts of the country, but—his Walt Whitman in Hell was meaningful to me, particularly the questions regarding America and its future.

deNiord: Hummer’s from the Deep South and you’re from Philadelphia.

Jackson: I think like many good poets he’s really angling back toward his origins. I think it’s an inner quest to know thyself.

deNiord: Oh, okay. You think that’s what it is.

Jackson: I think that’s where the poems take us. Not in any narcissistic way, but in illuminating the mysteries of the self. I know that’s been my experience when I’ve read certain poets who seem to cast just a brief flash on why we’re here.

deNiord: Yes.

Jackson: And our roles, our relationships.

deNiord: Speaking of formative years, the Dark Room Collective, how influential that was to you . . .

Jackson: Yeah, I mean, yeah. You know, next year will be the fifth book, and—

deNiord: The Absurd Man.

Jackson: Yes.

deNiord: After Camus, right?

Jackson: Yes, Camus. Yeah, but I feel a great sense still of indebtedness to my peers in Dark Room Collective and Cave Canem, their journeys have been inspirational to me, but still maybe more poets like Gwendolyn Brooks. You know, going back to Bruce Smith’s question. There is a poet whose formalism, like other American poets, like Adrienne Rich, for example, James Wright, whose formalism is a pathway to an authentic space of innovation and voice, achievement of voice.

deNiord: And you feel that formalism is essential for that.

Jackson: It’s the training ground for all of it. For all those poets, it’s their training ground, as many scholars have observed, a breaking of style is almost necessary toward a sense of mastery.

But to continue your topic: I tend not to hover too long in interviews about the Dark Room Collective but to simply express my gratitude for their example, their poems, their essays, their insights. My sincere hope is that someone will come along and write a cultural biography about the Dark Room Collective, that formative period of our lives, not necessarily a biography of me.

deNiord: Part of it would.

Jackson: Yeah, yeah, but I think what I’m trying to say is those particular moments were nurturing. But I have also been nurtured by being a father of four children. I say children, but three of them are adults now. I have one fifteen-year-old, soon to turn sixteen.

deNiord: How old is Langston now?

Jackson: Langston turns twenty-seven in November.

deNiord: So he’s your oldest.

Jackson: Yes, and my daughter Anastasia turns twenty-three in October. My stepson Dylan recently had a birthday, the big twenty-one. I have been enriched as an artist because I am a parent. Not that an artist needs to have such an experience, but the epiphanies come your way. As a young man, for example, I cultivated almost intentionally a certain kind of seriousness, an intellectual acuity. And I think it was chiefly reactionary because my demographic was demonized or portrayed as not capable of carrying and contributing to important humanistic conversations. I think of one poet’s assertion in a poem: “Nigger, your breed ain’t metaphysical.” That was a tough line for me as a young man to read in a poem, even if cast in a voice other than the poet. So I think I cultivated—

deNiord: The comeback to that apostrophe, “Ain’t exegetical.”

Jackson: That’s right. You’re beyond explication of text. Yeah. I guess what I’m saying—since becoming a father I have abandoned such posturing; it’s not a good example for the youth. I am maintaining a balance by trying to be a lighter person.

deNiord: A lighter person?

Jackson: Yes, more whimsical, finding great joy in my life and celebrating that.

deNiord: How’s that going?

Jackson: It’s difficult in the age of Trump. (Laughs) It’s difficult to read that the state of Alabama is working to rescind a woman’s right to abortion—you know what I mean?

deNiord: I do.

Jackson: I think the great example of people like Gerald Stern, who is also important to me, is to live with a level of joy, in the ecstatic even in the face of, in defiance of, those forces that would diminish our freedoms.

I think the great example of people like Gerald Stern, who is also important to me, is to live with a level of joy, in the ecstatic even in the face of, in defiance of those forces that would diminish our freedoms.

deNiord: That’s really nicely put. In your last book, Roll Deep, you ventured out more broadly in an international way than your previous books, writing poems with such titles as “Spain,” “Kenya,” “Brazil,” “Greece.” There are also several poems about race, the agon and bliss of romantic love and marriage, and a few credos in the form or litanies. I’m particularly drawn to the last litany in Roll Deep, “Why I Write Poetry,” which beguiles with such surprising lines as: “Because I wish I could speak three different languages / but have to settle for the language of business and commerce.” You majored in economics in college, right?

Jackson: Actually, I was an accounting major in the business school at Temple University, a practical decision being from the working class, but I could not abandon wholly my love of literature and, again, used all of my electives in English classes. I was recently thinking about how I had not noted the importance of this Introduction to Drama course and its impact on my growth, taught by this blowhard of a guy, a local playwright who had it in for Bertolt Brecht. But he loved Molière and Chekhov. But the gift was learning to listen to the literariness of everyday speech, everyday language.

deNiord: You grasped the ironic reality of having to “settle” for the unpoetic “language of commerce” as a prerequisite for writing poetry.

Jackson: I hear you. That settling is knowing that the language of business is never literary, with all its dead metaphors of war and competition.

deNiord: Your voice has matured in an existential way, addressing such formidable subjects as “shame,” which you claim leaves us perennially empty despite our refueling, your exasperation with America, with which “you’ve had enough” (“Stand Your Ground”), your view of the future where you see in your children your own “bulging face / pressing further into the mysteries” (“On Disappearing”), and a few enchanting pastoral poems that praise the beauty of Vermont’s Addison County and Mt. Philo. You create a fascinating lyrical dialectic between your disinterested, impersonal eye on those countries mentioned above and your sociophilosophical views on life as you face your sixth decade.

Do the new poems in your next book, The Absurd Man, which is due out next year, continue this dialectic strategy? Or are they about something else entirely?

Jackson: I believe, in a way, the poems in The Absurd Man are a continuation as I am still asking questions of lyric truth and the poet’s quest for meaning, which perennially torments us. In a way, we are all Sisyphean, except for those, of course, who are disengaged from their feelings and from the great family of nature and life. Man is tragic, at core, but the salve of art and beauty, of friendships and family, wrestling with the questions contain us, modestly and profoundly, until our dying. The connection to the social and political dimensions is that once we face this fact we fight with pen and breath for a human existence in which each of us can possess a bit of dignity and purpose.

However, I am still, with these poems, in the body and honor my journey with its falterings, hesitations, and triumphs. My regret with the book title is that several friends, upon hearing it, thought I was referring to Trump. We are living in an age of absurdity, but I am casting for wider seas.

We are living in an age of absurdity, but I am casting for wider seas.

deNiord: You conclude your poem “On Disappearance” with these vatic lines:

I am a life in sacred language.

Termites toil over a grave

and my mind is a ravine of yesterdays.

At a glance from across the room, I wear

September on my face,

which is eternal and does not disappear

even if you close your eyes once and for all

simultaneously like two coffins,

Were you influenced by any poem or poet in particular when writing these lines? They echo Gilgamesh and King David.

Jackson: Not directly; as you know, literature, myth, and songs grant us echoes. Our great fear is unwittingly borrowing from our elders and masters. The subconscious clings to song. I think in “On Disappearing,” I might have been channeling Clifton, Baraka, Lorca at points. But writing the poem was a remarkable experience because I felt an outside force at work, some great swell of emotion and surge of all my family, both blood and unrelated, speaking. The dead asserting itself from the other side.

deNiord: There is both resignation and chutzpah throughout Roll Deep, a terrestrial Homeric journey from your hometown of North Philadelphia to distant countries and then interior landscapes. You roll deep in the sea of this real and metaphoric journey, concluding your poem “Stand Your Ground” with these lines:

Think:

our watermelons have so many seeds, and we,

galaxy in us, dissolve our supernovas. The mysteries we have,

an unmitigated burning of sound and fury, not

organism of one, but organs. America, I’ve had enough.

You conjure both Faulkner and Whitman in these lines, and then conclude with an echo of Ginsberg’s apostrophe to America in his poem “America.” But your poem focuses on race here in a strident, contemporary way that’s both literal and figurative. Could you talk a little about the provenance and composition of this poem, which is also a “double golden shovel”?

Fortunately, we have a long tradition of protest and resistance, of which Ginsberg is among many American poets who express their frustration, but as with Langston Hughes, it issues from a place of belief in the power of love and possibility.

Jackson: I think Terrance Hayes is one of the geniuses of my generation, and his formulation of the golden shovel is evidence too of his generosity, how he continually honors ancestral poets, his literary lineage, and ours.

The frustration we experience, those of us who believe strongly in the individual rights of all humans as articulated in our founding documents, is palpable and real especially when we turn to headlines and news outlets. The assault on the humanity of black people is well documented in America, and yet laws like Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” reinforce entrenched fears we carry of each other. Fortunately, we have a long tradition of protest and resistance, of which Ginsberg is among many American poets who express their frustration, but as with Langston Hughes, it issues from a place of belief in the power of love and possibility. The last line of my poem is true to my occasional hopelessness but my countering emotions of “We will not give up on each other.”

June 2019

Two of Jackson’s poems appear in the Summer 2019 issue of WLT.