Singing Back to the World: A Conversation with US Poet Laureate Ada Limón

The following interview with Ada Limón took place shortly after her appointment, in July 2022, as the 24th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Although I prepared several written questions for Ada about her poetry, her influences, her most recent book of poems, and the projects she’s planning to carry out as the next Poet Laureate, I found her so affable, relaxed, and knowledgeable about poetry, as well as life in general, that I soon felt I was engaging in more of a stimulating conversation with someone I had known for a long time rather than conducting an interview with a stranger. When the interview ended after close to an hour, I felt we had only just started to talk about her poems, the current state of poetry in the US, the relatively recent burgeoning of diversity among American poets, her powerful use of the body in both literal and metaphorical ways, her deep connection to animals and plants, her keen sensitivity to inanimate and dead things, W. H. Auden’s claim that “poetry makes nothing happen,” her ancestors, her childhood home of Sonoma, California, her grief, and much more. I felt lucky indeed to have this opportunity to talk with Ada at this momentous time in her life and career.

Chard deNiord: Ada, let me begin by saying congratulations on being named poet laureate of the country and on the publication of The Hurting Kind, your newest book! I’ve loved reading your poems while preparing for this interview—it happens fairly rarely that you want to pick up books again and again, so the work just becomes deeper and deeper. An interesting coincidence occurred while I was reading The Hurting Kind. Over the past twelve years since I started interviewing poets, I’ve often started my interviews by asking my subjects, What hurt you into poetry? W. H. Auden famously wrote in his elegy for Yeats, “mad Ireland” hurt him into poetry. You confess in your title poem that you are the hurting kind, not someone who causes hurt, but someone who’s vulnerable to it. You write, “I have always been too sensitive, a weeper / from a long line of weepers. / . . . I keep searching for proof.” Can you recall what hurt you into poetry and just what proof exactly you keep searching for?

Ada Limón: One of the things that I remember even as a young child was my attachment to the world, my attachment to even the rocks that we’d find at the ocean, or leaves that would fall, and I’d wanna keep them. And I had to be talked out of taking everything I found in the natural world home with me (laughs). My stepfather and my parents were very clear—they would say, “Now, you know, these rocks belong here. They belong at the ocean.” I had to really be released from my obsession with wanting to keep everything because I became so attached to things. That was from a very young age, and I still have it. I’m laughing because I say that I don’t do it anymore, but I’m looking at my desk and all these stones that are around me from these beaches and walks and from the river.

Ada Limón: One of the things that I remember even as a young child was my attachment to the world, my attachment to even the rocks that we’d find at the ocean, or leaves that would fall, and I’d wanna keep them. And I had to be talked out of taking everything I found in the natural world home with me (laughs). My stepfather and my parents were very clear—they would say, “Now, you know, these rocks belong here. They belong at the ocean.” I had to really be released from my obsession with wanting to keep everything because I became so attached to things. That was from a very young age, and I still have it. I’m laughing because I say that I don’t do it anymore, but I’m looking at my desk and all these stones that are around me from these beaches and walks and from the river.

So, I think that was part of it, that there was a deep attachment to the world, and I think the other part was, I remember—I think I was fifteen—really having the moment of recognizing that we were all going to die. Not just recognizing that we’re all going to die, but really recognizing that I was included in that “all.” And it really floored me. It was enough that I went to sleep and cried, and I just kept thinking about losing everyone. I kept thinking about what I would miss. I think it was that moment that I thought, Oh, this life is urgent (laughs), and that I really needed to appreciate it and to sing it and to hold it as closely and as dearly as possible. I think that was the moment, really, that I knew I needed to somehow sing back to the world, somehow give an offering. I didn’t know what it was yet, but I knew there had to be an offering.

deNiord: As Elizabeth Bishop says about the art of losing in “One Art”: Write it.

Limón: One of my very favorite poems . . .

deNiord: What you were feeling at that point about your own life: Write it, begin writing it somehow . . .

A reviewer for The Guardian recently called you a poet of ecstatic revelation. Indeed, in poem after poem, you commit a kind of poetic sorcery in which you transform ordinary things like the valley in which you grew up—your dog, trees, horses, forsythia, snakes, fish, along with myriad other things and beings—into extraordinary things through the powers of your observation, description, imagination, and feeling. In your poem “Not the Saddest Thing in the World,” you write: “I go about my day, which isn’t ordinary, / exactly because nothing is ordinary / even when it’s ordinary.” When did you first discover your gift for transforming “things” into ironic sources of revelation? Was there any one poem that you might have written as a child or teenager or a young adult that inspired you to start translating quotidian “things” into sources for ecstatic poetry?

Limón: You know, I have always felt that sort of sense of the aliveness of the world, and there’s something about it that moves through me that it feels like, Oh, right, I’m not alone in this world. I’m connected to the trees, the animals, the plants, and everything has a quality of aliveness to it. As a young child, I remember having deep discussions with my Labrador, Dusty (laughs), at probably nine years old, and really feeling like there was no part of her that wasn’t understanding what I was saying, and we would sit by a creek bed and talk. I was alone. I grew up in Sonoma, California, and was able to cross the street and go to the creek and fall asleep. I’d sit with my dog and just have discussions.

I think that those sorts of moments, and the memory of those moments, always were about that kind of connection and aliveness that the world offers. I think that comes very naturally to me. If I stare at something long enough (laughs), I feel like I can see its importance. I can see its life force.

deNiord: It sounds like you were blessed with this, because there’s just so many people in the world that we read about every day who have what’s called in Greek sclerokardia, hard heart, who just don’t talk to their dogs. I’ll pick up rocks and feel this way, which reminds me of my next question for you. William Blake wrote as one of his Proverbs of Hell, which are really holy proverbs, “The most sublime act is to set another before you.” You perform this act repeatedly in your poetry. It comes naturally. What do you find particularly sublime about placing others, whether animate or inanimate, before you?

Limón: I think there’s a level in which it’s important for me to honor things and people, and that kind of honoring feels like there’s so many undersung things in the world, human beings, life, people that pass away every day that had extraordinary things happen to them. Did extraordinary things. And they’re just forgotten. Even as a young person, that felt like a missed opportunity, or it felt like a huge loss. I think when I say I’m a weeper, I am the hurting kind, that feels like, how are we not still talking about this person? And I think that when you use the word blessed with this, sometimes I have wondered if it’s a curse, because I’ll say . . .

deNiord: You know what? It could be both.

Limón: . . . because I do think that there’s a part of me that feels like I really want to hold everything up. That it’s not—my poetry, of course it’s about me, I’m in it, you know—but I like for it to be a holding up of others and, in some ways, am hoping that it allows other people to look deeply and honor things and people in their own lives.

deNiord: You know, it’s fascinating that the hurting kind line comes from your poem about your grandfather. Where you’re asking him, What kind of horse did you have when you were little? and he says, Oh, well, just a horse. It’s like no big deal, but to you, it was this huge deal. Then for some reason, you feel hurt after asking this question, a hurt that you say is in the bones of your ribs. It’s this really organic hurt that you feel, but that kind of conversation or response from another wouldn’t really affect most people, you know. Your grandfather said, Oh, it was just a horse, no special kind, but to you, it was this extraordinary being that hurt you. It prompted you to say that you were the hurting kind.

Limón: Yeah, absolutely. I think there’s a part of me that feels like it was so wondrous to me because he had this incredible life, and here he was dying, and the way that he could just say, Listen, no one needs to remember me. He was saying, Oh, it’s not important. And I was saying, But everything you’ve ever done is important to me.

deNiord: Speaking of animals here, they are such a huge part of your poetry, as well as plants, and you’re a poet of the body in so many of your poems, your own body as well those of animals and plants—a fledgling dove, trees, a sparrow, a bald eagle. I’m particularly fascinated by the shaman-like leap you make in your poem “Against Belonging,” in which you describe three garter snakes inhabiting you. You write, “Sometimes I feel them moving around inside me, ‘hissing’— / what cannot be tamed, what shakes off citizenship, / what draws her own signature with her body / in whatever dirt she wants.” These lines resonate as a kind of credo that embraces the wild within you as a citizen of nature over against any national identity. How would you talk about this poem, say, to a group of students who might ask you about the poet’s inherent inclination to be “subversive” in the Socratic sense, “refusing to be tamed,” as you state here, redefining citizenship in terms of declaring your allegiance foremost to the natural world as a denizen of the Earth over against your citizenship of a country?

Limón: I think that’s a really beautiful question. I think it’s been something that is very essential to my being, not just as an artist, but as a human person and a human animal (laughs), which we are. I think one of the things about that poem is it’s a deep philosophy of mine, which is: Who do I belong to? Where do I belong? That’s a question that people have asked forever. I always think of–I’m an atheist, I’m not a practicing Buddhist—but I love the story of Siddhartha, the story of the bodhisattva, when the Buddha was on his meditation under the bodhi tree and before he became the Buddha, one of the last asceses that visits him says, Who do you think you are to become enlightened? Who do you think you are? And what does he do?

deNiord: He touches the ground.

Limón: He points to the earth. That to me is like, I belong anywhere, because I am a citizen of the planet.

deNiord: This is so interesting and important for you to say as the poet laureate of the US, where someone might expect you to say foremost, I’m a citizen of the United States, and that’s my identity. You’ve got this wonderful poem called “A New National Anthem,” where you redefine the country and your affiliation with it by rewriting the words of the national anthem so beautifully. Your voice complements the rich cultural and racial spectrum of US poets laureate over the last ten years: Natasha Trethewey, Juan Felipe Herrera, Tracy K. Smith, Joy Harjo. So many budding poets from diverse backgrounds, along with many women also, feel hopeful in a way they haven’t before about their future as successful poets. Is there any particular message you would like to send the literary community of America in general, about the importance of equity and opportunity for those who have, throughout most of America’s history, been disenfranchised and neglected as aspiring poets from diverse backgrounds?

Limón: I feel like all of those wonderful poets laureate have been such mentors and friends throughout the years. Just hearing their names makes me feel emboldened and hopeful that they’re such incredible leaders of our time. One of the things that I keep coming back to is that what’s happening right now in the poetry world feels really expansive. You can pick up any anthology and think, Oh, it’s not the same twelve people from twenty years ago. And now you get to look up this person and go, Oh, I didn’t know this person existed. I love that. Yet even as that’s happening now, we also have to go backward and start to expand the canon a little bit more too, because I think that this current moment is a result of the incredible work that the ancestor poets did to get us to this place.

So, I think that we have to start calling back and be like, okay, we love Whitman, we love Dickinson, but those are not the mommies and poppies for everybody. It is more than that. We have to include Neruda, we have to include Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, we have to include the cultures from outside the country that the poetic ancestors are coming from, that have made these voices now as powerful and vibrant and diverse as they are in the present contemporary poetry scene. That’s something I find really important to do.

What’s happening right now in the poetry world feels really expansive.

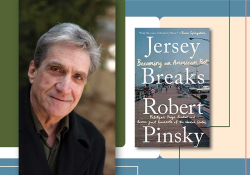

deNiord: I’m sure that’s going to be part of your mission. Speaking of some of the old-timers here, you were a student of Philip Levine at NYU, I think. In fact, you’ve written a moving elegy for him titled “How We Are Made.” Could you talk a little about his influence? I know you shared a love for the same landscape around Sonoma, California, and that valley where you grew up, which he called “our valley” and you call the valley of the moon. There’s a ferocity and spareness in your work that’s similar to his in many ways, I think. I just wondered if there was a big influence there.

Limón: He was my very first poetry teacher in graduate school, taught my very first graduate-level workshop, and he was notoriously tough. I think one of the real gifts that he gave me, aside from his work, is that he really taught you what to fight for because he had his own opinions and he’d tell you, Listen, you can take it or leave it. I’m gonna be tough. I’m gonna tell you what I think. You know, I’ve been doing this for eighty years. One of the things he really taught me was that you had to know what to fight for in your own poems. You had to know what was essential. So, if he said, I could give or take this poem and it wouldn’t matter to me, you had to be like, Oh no, I know there’s something redemptive. I know it’s here. I know this is whatever it is. Or you take the poem and know that he was right and toss it in the trash. But you would remember that it was your job, not his job, to tell you what was important in the poem, that you had to know. His toughness as a teacher was actually really important to me because I think it made me stronger as a writer, and he taught me what to fight for.

deNiord: I see a lot of the same ferocity and courage in your poems that he has, and I wonder if that rubbed off on you.

Limón: One of the things he taught me, and the thing that I take to heart, is that he took poetry really seriously. It’s almost to the point where I have friends who’ll be like, You need to play a little bit . . .

deNiord: To lighten up a little bit.

Limón: And I can be funny in my poems, I think. But I do think that even when I’m funny in my poetry, there’s a seriousness behind it. And that seriousness and that level of, almost like a solemnity—this is an art form that is incredibly important to me. That, I think, is very much related to my relationship with Phil.

deNiord: Matthew Arnold called it high seriousness back in the nineteenth century. I think that’s what you’re trying to get at a little bit. You’ve resumed the wonderful podcast that Tracy K. Smith started called The Slowdown, which the quarterly journal Electric Literature has called “a literary once-a-day multivitamin.” How are you enjoying this undertaking in which you talk about and then read a poem you love to the American public?

Limón: I just adore it. I love doing it. It’s a lot of work, but it’s wonderful. For me, as you know, being an artist, you are someone that oftentimes loves being alone and loves being alone with your reading and your work . . .

deNiord: And your dogs.

Limón: (laughs) . . . and I think that one of the great gifts of this is that I get to talk about other people’s work and I can write a little thing that sort of enters you into the poem, but then I get to celebrate all these great voices that are out there. That has also been just a huge gift because it changes my reading: when I read a book or an anthology, I tend to be reading for things that I want to highlight and celebrate. So, it encourages me to do a lot of reading, which I love.

deNiord: You also have a wonderful community of writers around you, friends from graduate school as well as new friends. I noticed in your notes to The Hurting Kind that you mention Natalie Diaz, Jason Schneiderman, and Major Jackson. And Gabriela Mistral, going back. Plus Camille Dungy, just to mention a few. How would you say this community of writers has supported you and inspired you?

Jason Schneiderman, & Camille Dungy.

Limón: I’m very suspicious of the idea that we make art by ourselves. Of course, we do have to be in our rooms and we have to have quiet. But there’s so much of it that’s community. Even if I’m reading someone’s work, that’s community. And I think that the support and friendship I have with such incredible artists who are not just encouraging me to keep doing what we’re doing, but I’m also inspired by every project they undertake. Anytime Natalie’s doing something, I’m like, Oh, tell me more about that. What do you want to know? And Camille’s working on an incredible book right now about gardening, and I just can’t wait to read it. And Matthew Zapruder and his work about exploring poetry. Every time they’re making something, I get more and more inspired that,we are all in this together. We’re all talking about this art.

And it’s not just the poetic support. It’s also the emotional support. I feel really lucky to have those kinds of friendships, because we don’t make art alone. We make art in community.

We don’t make art alone. We make art in community.

deNiord: That’s very important to mention. Well, you’re in Kentucky now, is that right? You’ve been there for quite a while, and you seem to love the horses there, the horse culture, a lot. I was just wondering: after the terrible floods there in eastern Kentucky—you’re in north central Kentucky, in Lexington—this leads to another question, too. Thirty-seven people perished in those floods, just a devastating natural disaster. How do you see poetry as a source of solace to people who who’ve just experienced such tragedy, and have you been inspired at all to write anything about those floods or talk to folks in Kentucky about what’s happened?

Limón: It’s interesting that you bring this up because just last night, I was honored at our downtown Thursday Night Live, sort of like a farmers market at night, and everyone comes out and there’s live music. With the people who were doing the honoring, I asked about eastern Kentucky, and a lot of people there were from eastern Kentucky. We were talking about this disaster, about what’s it like, and it felt to me like the closest thing that I know of is fire, being from California. We started comparing what it is, and we were talking about these elemental things, fire and water and the destruction. And it just struck me about how there’s a deep obliteration that happens because everything gets touched by it. Everything gets ruined by fire, everything’s ruined by flood. Even if your life is saved, almost everything you have is gone, and I think about the reminder of what poetry can give us when those things happen is, again, Where do we belong? What is home? And sometimes home is not the physical thing. Sometimes home is literally like the flame you kindle in your heart, and the trees and the things that have survived around you.

I think it’s important to remember, again, what citizenship is, that we are citizens of the planet, and poetry can offer that sense of connection that is larger. Also, let’s face it, poetry is a great place to grieve, to weep, to say, This is really hard. I lost a lot. There are wonderful poems that can allow that to happen.

Let’s face it, poetry is a great place to grieve, to weep, to say, This is really hard. I lost a lot.

deNiord: You write a lot about grief as well. There’s this wonderful poem from Gilgamesh about this that Herbert Mason translated. It goes: “All that is left to one who grieves is convalescence, no change of heart or spiritual conversion, for the heart has changed. And the spirit has been converted to a thing that sees how much it costs to lose a friend it loved.” There’s silence in your poems, where you can’t speak or even write in the face of such a devastating loss as the flood or the death of a loved one. How do you envision getting that silence into your poetry, between the lines or between the words?

Limón: I think that silence is one of the most important parts of poetry. That’s the thing, that’s the gift, that’s what makes it the form. That’s what makes a poem: it’s not just about the words that are on the page, but it’s the appreciation of breath that’s in the caesura and in the line break and in the stanzas, and it’s the white space all around the poem. And that’s the place for breath, the place for silence, and it’s as much about those spaces as it is about the words. I think those are places where not only we’re allowed to breathe, but it’s also the places that we are allowed to enter as a reader. We enter that place, it becomes a room we walk into, and there’s actual silence around it. It’s not just all the words of the prose writer all the way to the end of the page. Instead, it’s that idea of walking in, in silence.

deNiord: And you can get it in poetry more easily than prose, I think.

Limón: Absolutely. I think it’s very essential to how a poem is made.

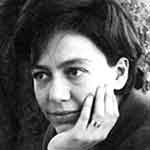

deNiord: So, Alejandra Pizarnik, whom you must revere, because you put that little poem at the front of your new book, The Hurting Kind, which is called “I Ask for Silence.” And it goes: “though it’s late, though it’s night, / and you are not able. // Sing as if nothing were wrong. // Nothing is wrong.” Could you talk about that poem a little bit and her influence? Especially given that World Literature Today goes out to the world, not just to the United States.

Limón: She’s one of my favorite poets and just an incredible Argentine writer. She’s from Buenos Aires, and I was actually just there. One of the things that always fascinates me about her is that, since we were just talking about silence, she is very interested in the failure of language. I think, as poets, most of us are, but she really makes a case for this idea that I can do this, but it’s never going to be what I truly want to do that’s in my soul. I’m trying to explore it. So, she’s always interested in how the poem is working, but also how it’s failing. There’s something beautiful in that intention of trying to not just show you what is possible on the page, but also how it’s not doing everything she’d love it to do.

I also think that she was someone who was a tortured soul in a lot of ways. But she found, I think, a lot of peace on the page. You can read the story of her life and try to sum her up and think of her as a tragic figure, but then when you see this power on the page, you think, Oh, this is where she found her solace. This is where she found her power.

deNiord: And people forget maybe that she was Ukrainian.

Limón: Yes. I think she was born in Argentina, but both her parents were Ukrainian. I have dear friends that are Ukrainian, and there is a certain sensibility that is really about power and strength and that interest in a ferocity of life.

deNiord: Which we’re seeing now, very much so. What you said about her a few minutes ago, about her sense of failing but continuing to write till the end of her life, reminds me of that famous Beckett quote: "Fail, fail again, fail better."

Mistral too is an influence, right? Could you talk about her just a little bit?

Limón: I think it’s funny because here in the United States, you often hear so much about Pablo Neruda, but Gabriela Mistral was Neruda’s teacher, and if you go to Chile, she’s on the money.

deNiord: (laughs) That’s right. Like in so many South American countries, poets are on the money. Like in Brazil, where one of Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s poems, along with his picture, was on one of Brazil’s paper currencies in the late 1980s.

Limón: She’s literally on the money. She’s everywhere. There are statues of her, all these things. And I think she gets a little undersung too. Neruda was a senator and was controversial in some ways, but he also did incredible work; his goal was basically to become the Whitman of Latin America, to put Latin American poetry on the map, and he did that, in an incredible way. But I think sometimes we forget that the person before him was Gabriela Mistral . . .

deNiord: Who was already on the map. And won the Nobel, by the way.

Limón: Won the Nobel, and was really an essential lyricist of the natural world and also of womanhood and her later life. She was a queer woman, and I think she just did so much in creating her own mythologies, and she did that so well. She’s creating these deep mythologies, and that has been important to me in my own work.

deNiord: And, finally, Lorca.

Limón: Yeah, I adore Lorca, for many reasons. There are so many poetic philosophies out there, and I’ve never really ascribed to any of them. It’s similar to my idea of religion. I just believe in possibilities (laughs), all possibilities. For me, Lorca’s theory of duende was the very first thing I ever read of a poet that truly made sense to me, because he talks about how the muse is outside, and you get the muse, and then the angel, that’s the visitation. He talks about both of those things as being very, sort of, western European. Then the duende lives within us. It comes up from the soles of our feet. It lives in the recesses of the blood, and it’s something that we can call and tease out of ourselves. When you feel that duende, part of what you’re experiencing is that earthiness, and then also, at the same time, that idea of acknowledging mortality: the death sounds are with the dark sounds, the death sounds are with the duende.

deNiord: Americans don’t hear that enough, you know? Even in our best poets. I think Walt Whitman would have loved Lorca, but he wrote that the proof of the poet is that his country, her country, absorbs her as affectionately as she has absorbed it. Yet the poet often plays a prophetic role as well, writing caveats and provisos and even diatribes as Allen Ginsberg did, Adrienne Rich, Robert Bly, Natasha Trethewey, Amiri Baraka, Joy Harjo, Nikki Giovanni, Galway Kinnell, Gerald Stern, and even Whitman himself later on in his essays called Democratic Vistas. How do you envision combining your affection for America with your truth-telling as a poet during your tenure as poet laureate? I wish we had time to read “A New National Anthem,” because that poem certainly provides a memorable corrective.

Limón: Oh, thank you. I think that poem is actually part of my philosophy around that question, and two things always bring me back to loving this country: the people and the land. To stand in a place like Yellowstone or Yosemite, or to stand in the Red River Gorge, or in a small creek down the street, those places and that connection to this North American continent that is so incredibly gorgeous, I think, always remind me of what I want to sing about, what I want to talk about.

Two things always bring me back to loving this country: the people and the land.

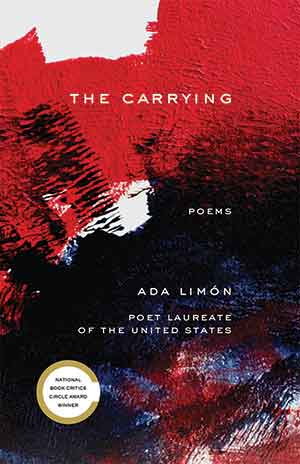

deNiord: Let me just read the end of it, because I think it’s important as you’re alluding to it here. You say it should be “a song where the notes are sung / by even the ageless woods, the short-grass plains, / the Red River Gorge, the fistful of land left / unpoisoned, that song that’s our birthright, / that’s sung in silence when it’s too hard to go on, / that sounds like someone’s rough fingers weaving / into another’s, that sounds like a match being lit / in an endless cave, the song that says my bones / are your bones, and your bones are my bones, / and isn’t that enough?” (from The Carrying). As opposed to bombs bursting in the air, right? That’s really beautifully put.

Limón: Thank you. It’s about that groundedness. It’s about that connection.

Limón: Thank you. It’s about that groundedness. It’s about that connection.

deNiord: So much of your strength as a poet derives from your courage to write both ferociously and tenderly out of the mouth of your wounds, hurt, body, and grief with a transpersonal self that crosses over from your speaker to your reader. This transactional self of yours divines others you’ve loved, including animals, family, and plants as well as inanimate objects. This reminds me of what John Keats called negative capability, the poet’s capacity to immerse herself “in mystery, uncertainty, doubt, without an irritable reaching after fact and reason.” You execute this cathartic crossover in poem after poem; it’s your “carrying,” which is the name of your next-to-last book. As you think about your upcoming tenure as the next poet laureate of the country, how do you envision talking about and teaching poetry as a literary and spiritual anodyne for helping cure the internecine political turmoil that has polarized this country so divisively over the past ten years?

Limón: I think that the opportunities we have to really connect with our own humanity are very rare, and I certainly don’t think they’re provided on social media. And I don’t think we have those opportunities, in most of our lives, as we work and keep our heads down and try to work through a pandemic and pretend it’s not happening. We’re losing people like dear poet Dean Young, who just passed away. I feel like there’s so many of us who are just so numb . . .

deNiord: You know that 460 people are still dying every day from Covid?

Limón: . . . and I get it, I understand why we have to be so numb, because we do have to go about our day and do our tasks and all those things. But I feel like that numbness becomes very dangerous, and I think that sort of disconnect we have from our emotional selves is what causes people to really live in unidentified rage.

deNiord: That’s a good way to put it.

Limón: So, I think that poetry and reading poetry, writing poetry, is a way of healing. And it’s not just in that cheesy way of saying, oh, you know, you just feel better. But it’s that you feel. And that is enough, right? Just to feel. And for one minute—you can read a poem in a minute and have this moment of, I am a real human being with feelings. I need to take care of that person a little bit (laughs).

You can read a poem in a minute and have this moment of, I am a real human being with feelings. I need to take care of that person a little bit.

deNiord: That is your anodyne in poem after poem. I couldn’t agree with you more. So, to return to something Auden said—I don’t know why Auden kept popping into my head while I was thinking about these questions . . .

Limón: I love Auden, so that’s great.

deNiord: He wrote in his poem “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” that poetry makes nothing happen. Although he did concede that it was “a way of happening, a mouth,” but what might you say in response to him about this assertion, if you had his ear at a party or in an elevator or in a tutorial?

I do believe poetry has the power to reconnect us with ourselves, and I think it has the power to reconnect ourselves with the earth.

Limón: It’s very easy for me to expound on the power of poetry. But I’m not naïve enough to think that it can fix the climate crisis. Or that it can save all of our souls. But I do believe that it does have the power to reconnect us with ourselves, and I think it has the power to reconnect ourselves with the earth. I think it’s also important for us to recognize that in its power to just be—it’s just a poem, one poem at a time, as we say—it can actually move around the world in a way that it’s not asking too much. As Rushdie said, A poem is not going to stop a bullet, but it will speak a truth and will connect us to a truth. I think that’s essential. So, I think it’s about how it moves in the world, that it travels one poem at a time, and that it does exist in a way to allow us to feel, to breathe, and to be present, which is an essential thing to reconnect ourselves with our humanity. I think, in another way, it’s also about recognizing that there is time for beauty . . .

deNiord: Slowing down.

Limón: . . . and for wonder. Because sometimes it’s really, really hard to have hope, and hope is work (laughs). And sometimes it’s hard to have gratitude. Gratitude is work, but I think beauty and wonder, they exist, they exist, and it happens. You can just look out and say, Oh, a leaf is falling, the seasons are changing. It’s a sense of wonder, a sense of awe, and sometimes that’s just enough. It’s not an answer; it’s an experience. It’s a question. It’s a curiosity.

deNiord: It could actually make huge things happen within a person who then might act in a way that’s more enlightened. So, Auden maybe was just half right.

Limón: And he would probably say that if he were here (laughs)!

deNiord: You know, he wrote that in 1939, just before World War II and as Hitler was on the verge of destroying the world, so I think that’s why he said that.

Well, Ada, it’s been really wonderful talking to you, and I wish we had another hour to continue our conversation.

Limón: And I wish we could have met in person. But I loved all your questions, Chard—they were really wonderful. I hope I did okay in responding to them.

August 26, 2022

Editorial note: Special thanks to Brett Zongker, chief of media relations at the Library of Congress, for helping facilitate this interview, and to Vaughan Fielder of The Field Office.

Ada Limón serves as the 24th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry of the United States and is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship. Of Mexican ancestry, Limón was born in Sonoma, California, in 1976. She is the author, most recently, of The Hurting Kind (Milkweed Editions, 2022) and of five other collections of poems. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, and American Poetry Review, among others. She is the host of American Public Media’s weekday poetry podcast, The Slowdown.

Ada Limón serves as the 24th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry of the United States and is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship. Of Mexican ancestry, Limón was born in Sonoma, California, in 1976. She is the author, most recently, of The Hurting Kind (Milkweed Editions, 2022) and of five other collections of poems. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, and American Poetry Review, among others. She is the host of American Public Media’s weekday poetry podcast, The Slowdown.