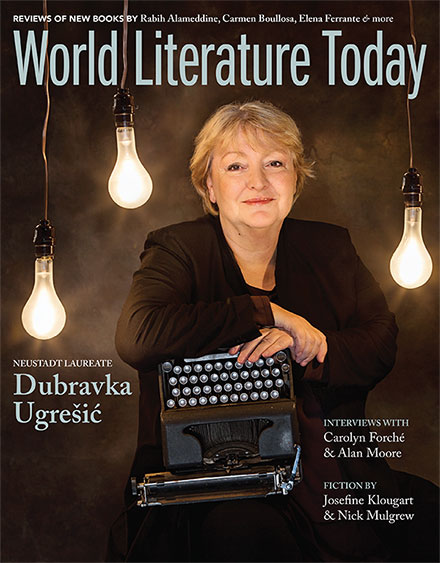

Dubravka Ugrešić and Contemporary European Literature: Along a Path to Transnational Literature

In 1997 I was offered a job to teach English to adults in Croatia. Of course I had been following the events that had torn Yugoslavia apart between 1991 and 1995; and just as I was learning what I could about the newly independent country of Croatia, Dubravka had already left it behind, in 1993, to go into exile first in Berlin and then Amsterdam. The irony is that I ordered two of Dubravka’s early books, to learn more about a country that, in fact, no longer existed, and where she no longer lived nor could feel at home. But these two books were a good introduction nevertheless: Steffie Speck in the Jaws of Life and Fording the Stream of Consciousness are both works of fiction and belong to a tradition of playful satire and black humor that was prevalent all through Eastern Europe during the communist era. As a student of Russian I had read both the classics and the Soviet-era satirical work that followed, so there was something that felt wonderfully familiar about her fiction and new at the same time. Were it not for the accident of history, so to speak, Dubravka might have gone on writing novels in this satirical vein, poking fun at her fellow writers, or lovesick women, or life in the little republic of Croatia when it was part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It is significant that the breakup of the country drove her into exile only four years after the fall of the Berlin Wall; it is also significant that the once-“dissident” writers of the Soviet bloc suddenly found themselves in a literary context that was utterly changed—they had freedom of expression at last, yes, but not necessarily the freedom to publish or be read; market forces suddenly determined everything that was published throughout the former Eastern bloc. The breakup of Yugoslavia meant not only the transition to a capitalist culture but also a severing of ties among the former republics that at times bordered on the absurd, as new dictionaries were created for each republic’s “language”—no longer known as Serbo-Croatian but as Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (and sometimes Montenegrin).

Now Dubravka found herself living in Western Europe but writing in Croatian, living in, as she calls it, a literary out-of-nation zone. Who would read her? Who was her audience? Whom was she writing for? Back then, perhaps only a few dissenting Croats or fellow exiles, unhappy with the nationalistic regime of the 1990s; her Yugoslav audience had virtually vanished. Would the Germans, the Dutch read her in translation? Could she find a place as a European writer? These were some of the questions I asked myself as I began to learn both about Dubravka’s biography and about life in Croatia in the late 1990s.

After the year I spent in Zagreb, I returned to the US and was heartened to see that Dubravka’s books were appearing regularly in English: Have a Nice Day, The Culture of Lies, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, Thank You for Not Reading, Ministry of Pain, Nobody’s Home, etc. I realized too that she had found a new voice—the voice of exile, one might call it—and that the bubbly, sardonic novels of her youth had given way, for the most part, to incisive, often heartfelt and angry, but always ironic and cautionary essays about life in post-Yugoslavia, in Europe, and in the wider world. Her works appeared not only in English but in many countries, in translation, and she has, so fortunately for us, found her place, at latest count, in twenty-seven languages.

After the year I spent in Zagreb, I returned to the US and was heartened to see that Dubravka’s books were appearing regularly in English: Have a Nice Day, The Culture of Lies, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, Thank You for Not Reading, Ministry of Pain, Nobody’s Home, etc. I realized too that she had found a new voice—the voice of exile, one might call it—and that the bubbly, sardonic novels of her youth had given way, for the most part, to incisive, often heartfelt and angry, but always ironic and cautionary essays about life in post-Yugoslavia, in Europe, and in the wider world. Her works appeared not only in English but in many countries, in translation, and she has, so fortunately for us, found her place, at latest count, in twenty-seven languages.

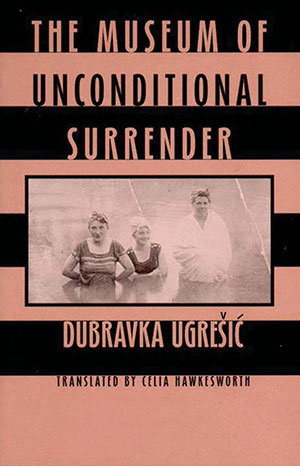

I would like to focus briefly on her novel from 1997, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, because it is the pivotal work written from her first exile in Berlin, and it is also a work that echoes and reflects the events of the late 1980s and ’90s in Europe. Before 1989 Berlin was a divided city, the very heart of the tension between Western and Eastern Europe; then, after the fall of the Wall it became the home not only to many refugees from the war in the Balkans but also to a host of economic migrants from Eastern Europe in search of a better life. Russians, Poles, Hungarians, Romanians, and let’s not forget East Germans all came in search of a new life in the open city of Berlin. Dubravka’s novel brings that transitional, transitioning city to life with its migrants, refugees, lost souls, artists, exiles—there are Bosnians and Russians but also Brits and Indians; we meet Americans and Portuguese as the narrator travels for her work. There are chapter headings in German, notably Wo bin ich?—“Where am I?”—and this refers not only to the narrator’s or an immigrant’s bewilderment in the situation of exile and a new language but also leads to the question Wer bin ich?—“Who am I?”—the question of identity totally turned on its ear, particularly for the former Yugoslavs, but even for the other ordinary migrants. Could a Russian now say he was German, or European? Was he still Russian? What is identity? How much of it is necessarily bound up in geographical location or place of birth; how much of it will be influenced by politics?

For that period of time in Berlin, Dubravka witnessed the distress of these immigrants and chronicled it, offsetting the passages set in Berlin with memories of her childhood, her mother and grandmother, and the dual loss of youth and home. The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a novel that is deeply rooted in European history but has become uprooted from its “Croatian” context or tradition—other than the fact that it was written in Croatian—to move into, I would say, a category of its own. If one must categorize a book, the way clueless booksellers sometimes do, we could say this book belongs to the literature of exile. But there are no shelves in bookstores for “exile”; you will find Nabokov under American literature, Brodsky under Russian, Joseph Conrad among the classics, etc.

Unlike many other works of European literature, Dubravka’s oeuvre is pan-European, in the sense that it deals with many different countries, and people from many different backgrounds and nationalities. Let me explain by providing a contrast. To name two of the most salient examples of contemporary European literature currently enjoying both critical and popular success in the US, there is, first of all, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, then Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet. The first is very clearly set primarily in Norway, and its hero is very typically Norwegian in many respects, albeit his wife is Swedish and they live in Sweden; Ferrante’s novels are even more bound to their location and its inhabitants—you could even say that Naples is a character throughout the novels. Granted, these are works of “fiction,” so to speak, whereas Dubravka is now writing principally nonfiction, but all her books feature a rich variety of characters and places, usually quite specifically described, but with an intent to reveal the universal nature of the dilemma or situation in which these passing protagonists find themselves.

The work of Dubravka Ugrešić stands apart from any specific European literature precisely because she comes from a European literary tradition that gave her the tools to gaze coldly on the dangers of classifying and codifying, of pinning labels, the dangers of conformity and submission to a nation or an ideology.

I have been thinking, since I was first invited to speak on this panel, of how I would situate Dubravka “in the context of contemporary European literature,” and my conclusion is, to be honest, that I cannot. If I think of the novels I have translated from French over the last decade, most of them are very ethnocentric, very much part of a French tradition, or certainly taking for granted that they belong to the realm of “French literature,” often catering to a French readership or, in any case, assuming that the primary readership will be French. There is no such easy assumption available for Dubravka’s work; in fact, she said herself in a recent interview: “I have passionately propagated the notion of transnational literature . . . a literary territory for those writers who refuse to belong to their national literatures” (Music & Literature, May 12, 2015). Again, if we turn to her biography, her geographical history, it becomes very clear why this is. Very early on in the conflict, Dubravka was expected to take sides and could not, would not. She chronicled her outrage and disgust at her countrymen in The Culture of Lies; she continues to target Croatia—now a member of the European Union—for its lack of transparency, its corruption, its multiple shortcomings. She has seen through the tawdry nationalism of flag-waving; she is appalled by the population’s fairly recent protests against the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia regarding the war crimes trials of men whom Croatians refer to as “heroes.” She has been a direct victim of that particular nationalism, but nationalism, as we hardly need reminding, is on the rise everywhere.

The work of Dubravka Ugrešić stands apart from any specific European literature precisely because she comes from a European literary tradition that gave her the tools to gaze coldly on the dangers of classifying and codifying, of pinning labels, the dangers of conformity and submission to a nation or an ideology. Nor is globalization the answer, as a reaction to nationalism; she illustrates this in Karaoke Culture, which describes a universal culture of dumbing down, conformity, and laziness. Dubravka’s work belongs, rather, to its own “transnational” category, a literature that defies and crosses borders wherever there are readers who are open to the outside world, who are not afraid of the other, the foreigner, readers who do not want to go through life building walls to remain in a comfortable, blinkered, nationalistic homeland. She writes for those who, like herself, defend supranational values—freedom of speech, empathy, justice, and integrity.

Buchillon, Switzerland