Crafting Serious Work Out of Mass Culture: The Early Prose of Dubravka Ugrešić

In 1978 Dubravka Ugrešić published her first short-story collection, A Pose for Prose. Life Is a Fairy Tale followed in 1983. The protagonists of these stories find phalluses in their hot dog buns, lend each other their characters, write letters to editors of publishing houses about their Daniil Kharms translations, and generally exist in a plane between signs, theory, and literature. This is the beginning of Ugrešić’s self-reflexive, ludic postmodernist style that brings into its fold discourses as wide ranging as advertising, journalism, and other forms of commodity culture, but also the canon of Russian literature in addition to its forgotten or submerged literary texts. Like other younger writers in Croatia at that time, Ugrešić flirted with the boundary of high and low, producing a prose identity emblematic of what Croatian critic Aleksandar Flaker characterized in 1983 as “literary in-betweenness.” This term referred to new literature for an urbane young audience that carved out a position for itself between traditional, elitist forms of culture and truly commercial and trivial literary genres (such as crime novels).1 However, playing with mass culture was more than just a formal experiment for Ugrešić. She used the signs and the material of the everyday to expound on theoretical preoccupations, to crystallize social relations, and to question gender norms and the possibilities of female subjectivity—all packaged and presented in a witty and humorous prose.

Ugrešić belonged to a generation of writers who cemented and popularized postmodern tendencies in Yugoslav literary circles, though this was by no means a uniform poetic. Interestingly, despite socio-economic discontinuities between socialist Eastern Europe and the late capitalist West, the artistic experimentation with postmodern techniques in Yugoslavia was more or less contemporaneous with its counterparts further afield. The appearance of postmodern artistic practices in Yugoslavia was coterminous with late socialism—a rather complex and contradictory period of the country’s existence that was also, at times, its most depressing. Yet it was also a time when artistic manifestations of the postmodern became more riotous and extensive, impacting all mediums of cultural production even as Yugoslavia was hurtling toward its demise. Metafictional, self-referential gestures were appropriated; fiction and critical theory were translated; fragmentary and intertextual techniques were duplicated—and quite enthusiastically at that. “In practically all instances,” writes Slovenian critic Aleš Erjavec, “postmodernism in the former and present socialist countries was apprehended as a positive phenomenon” signifying “the most recent trends emanating from the West and its cultural capitals.”2 Some of these particular influences include the demystification of the writer’s authority, a tendency towards metatextual gestures, the rejection of mimetic literary practices, the interrogation of the ontological status of reality, the exploration of non-referential properties of language, and, as already mentioned, negotiation between—as well as synthesis of—low and high cultural forms.

She used the signs and the material of the everyday to expound on theoretical preoccupations, to crystallize social relations, and to question gender norms and the possibilities of female subjectivity—all packaged and presented in a witty and humorous prose.

However, the literary critical establishment was resistant to the poetics of postmodernism, slow to adopt and adapt to new artistic and literary forms of expression. Writing in an author’s note for a new edition of Life Is a Fairy Tale, Ugrešić reflects on this time:

[Postmodernism] broke into the local literary milieu from randomly translated foreign articles. For the domestic literate public, postmodernism was like gossip from a distant literary world, so that gossip about a concept was adopted instead of the concept itself. Using my author’s notes as the only relevant source, critics concluded that the collection of stories was a typical postmodern product, which was a polite synonym for plagiarism.3

Plagiarism, suspicion, gossip: Ugrešić’s serious-minded critique of the domestic literary scene takes on the very same playful characteristics typically associated with postmodernism. She presents literary criticism as a closed, conservative activity that rejects foreign and strange elements (artistic innovation) and presents them as inadmissible into the designated sphere and discourses of art. What’s striking, in fact, about both the postmodern artistic experiments and the eventual theoretical response that followed is that they foregrounded radical formal innovation. This resulted in a hermetic, self-referential literary discourse of the 1980s that was characterized by a weak engagement with the problems of late socialism.

Ugrešić’s fiction of the late 1970s and early 1980s does have a historical counterpart in the world of Yugoslav aspirationalism and the pursuit of material well-being. “From the mid-1950s on the political climate in Yugoslavia permitted, and later even encouraged,” writes historian Patrick Hyder Patterson, “the growth of a deep and complicated relationship with shopping, spending, acquiring, and enjoying.”4 Throughout the decades, this popular culture became more entrenched with the arrival of international fashion and culture:

The country’s “lowbrow” mass media had indeed become astonishingly attentive to European and American movie stars and rock idols, just as they closely followed the latest twists in Western lifestyles and the ups and downs of Western celebrities and their hemlines. The coverage, moreover, was rarely all that politicized or critical. Exposure to the international culture of celebrity, entertainment, and diversionary escape spawned, in turn, a host of Yugoslav variations, elaborations, and imitations, yielding a motley assortment of mass-media offerings that ran the gamut from pop stars to sitcoms to sex symbols. (174)

While popular culture was not politicized, Ugrešić’s literary mediation of its codes and genres provides commentary on the intersection of gender and literary roles. Her early work tracks the processes and gestures of consumption as the promised terrain of satisfying desire that almost always remains a deferred satisfaction. The 1983 short story “Life Is a Fairy Tale” opens with “an ample young lady in a state of constant hunger” trying to satisfy her “incomplete personality,” the result of an unhappy love affair, by eating an endless stream of confectionery. The text reverberates with numerous “lacks,” most notably exemplified by the young woman’s day job on the filling assembly line at a biscuit factory and, later in the story, by the “piteous little member” of her male guest.5 Gratification of a kind arrives in a type of cake named “Fountain”: the enmeshing of erotic (most often phallic) symbolism with consumerism is not accidental, since objects of desire are partly fulfilled through their commodity image.

Ugrešić’s interest in the idea that mass culture itself consists of the production of desire is subject to a critique in the 1981 novella Steffie Cvek in the Jaws of Life. This short novel demonstrates how individuals get trapped within fictions sold to them by narratives prevalent in mass culture, commercial literature, and advertising. Steffie, a lonely typist from Zagreb, is looking for a man and trying to assuage her sexual and emotional frustration by taking clichéd advice from Lonely Hearts columns, fairy tales, and women’s magazines. As one commentator noted, Steffie actually fails “to conform to the myths of feminine passivity” precisely at the moment that she tries to enact them: as such, her immersion in popular culture is at the same time a deconstruction of stereotypes governing traditional femininity in Yugoslav culture.6

Steffie Cvek in the Jaws of Life is an ironic take on the pejorative, historically entrenched idea that posits women as “responsible for the debasement of taste and the sentimentalization of culture” since they are the primary consumers of mass culture.7 Ugrešić overtly signals her historical awareness of this position when her protagonist, Steffie Cvek, reads (and quotes from) Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Steffie copies passages at length about Emma’s “cold life,” her expectant waiting for an “event, a wind that will force a sail to her,” and her desire for love, which is “like a carp’s desire for water when it is on the table.”8 While a number of critics have analyzed this reference to Flaubert in terms of intertextuality and dialogism, it is equally a nod to the historically gendered pattern of mass culture: Emma Bovary is a great reader of sentimental romances, which are quintessential examples of trivial literature. Since the nineteenth century, women have been coded as consumers of popular culture, of cultural trash which, it is presumed, pacifies their lacks and insecurities. Steffie Cvek in the Jaws of Life deconstructs this bias precisely by demonstrating how crafting literature out of popular culture falls into the realm of theoretical-literary thinking, into the category of serious intellectual work.

Steffie Cvek in the Jaws of Life is an ironic take on the pejorative, historically entrenched idea that posits women as “responsible for the debasement of taste and the sentimentalization of culture” since they are the primary consumers of mass culture.7 Ugrešić overtly signals her historical awareness of this position when her protagonist, Steffie Cvek, reads (and quotes from) Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Steffie copies passages at length about Emma’s “cold life,” her expectant waiting for an “event, a wind that will force a sail to her,” and her desire for love, which is “like a carp’s desire for water when it is on the table.”8 While a number of critics have analyzed this reference to Flaubert in terms of intertextuality and dialogism, it is equally a nod to the historically gendered pattern of mass culture: Emma Bovary is a great reader of sentimental romances, which are quintessential examples of trivial literature. Since the nineteenth century, women have been coded as consumers of popular culture, of cultural trash which, it is presumed, pacifies their lacks and insecurities. Steffie Cvek in the Jaws of Life deconstructs this bias precisely by demonstrating how crafting literature out of popular culture falls into the realm of theoretical-literary thinking, into the category of serious intellectual work.

Ugrešić’s 1983 novel is a critical update of the association between mass culture and gender because it probes not only into female subjectivity but also female authorship. In her humorous short story “Lend Me Your Character,” first published in Life Is a Fairy Tale, Ugrešić opens with the epigraph “Is the pen a metaphorical penis?”, clearly alluding to the opening line of the classic piece of feminist scholarship The Madwoman in the Attic, by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar.9 Much like the two scholars, who seek to demystify the tradition of literary paternity that sees male sexuality as “not just analogically but actually the essence of literary power,”10 Ugrešić’s stories tackle the conditioning of social roles (subservience of women, for instance) in order to explore how they reveal entrenched prejudices in the literary creation and authority of voice.

In the historical dynamic whereby women are coded as passive consumers, the man is the author—and the example of Madame Bovary is relevant again here. As Andreas Huyssen notes, “woman (Emma Bovary) is positioned as reader of inferior literature—subjective, emotional, and passive—while man (Flaubert) emerges as writer of genuine, authentic literature—objective, ironic and in control of his aesthetic means.” Within this dynamic, Huyssen adds, “authentic culture remains the prerogative of men.” Authenticity ostensibly offers autonomy from mass culture that, by extension, presumes autonomy from the trivial preoccupations of everyday life.11

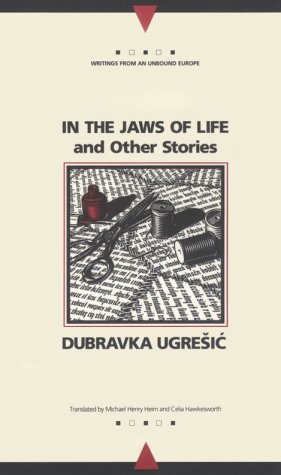

This prerogative is usurped in Ugrešić’s fiction. Steffie Cvek and her short stories from the same period are exemplary of a literary poetics where a female author finds originality not in an unspecified, organic talent but in rewriting, recycling, and reinserting. The blueprint of female authorship rejects the normative associations of artists and writers with sacred, immaterial notions of creativity. Ugrešić’s Steffie Cvek offers an alternative conception of writing in its use of sewing strategies that turn into their literary, aesthetic counterpart—namely, narrative techniques. Sewing terminology begins with a key of icons: a pair of scissors indicates cutting and various punctuation combinations signify gathering, smocking, or taking in. The opening chapter, “Designing the Garment,” is about “technique”—what kind of novel to write? with what kind of material?—and foregrounds the slippage between literary and dressmaking processes. Yet the novel never loses sight of the fact that sewing is women’s domain and technology: a technology of stitching and cutting that calls to mind strategies of citation and intertexuality. Indeed, her “sewing” of discourse can be read as an intellectual exercise that augurs the domestication of (postmodern) literary theory. It becomes evident, as the reader advances through the stitched novel, how deeply theoretical this exercise actually is. Steffie Cvek becomes an exploration of literary concepts while simultaneously trafficking in the clichéd and banal discourse of popular culture.

Crafting a critical discourse out of kitsch emerges more fully in The Culture of Lies, Ugrešić’s 1995 collection of essays published in response to the wars in Yugoslavia. The essays address what happens when popular culture becomes the platform for populist opinions and convictions, when aesthetic properties and commodities become politicized. While the political and social landscape of Eastern Europe changed around her, her longstanding interest in kitsch and phenomena of mass culture found a new function: intellectually acute critiques of ethnonational politics. Using Vladimir Nabokov’s writings on poshlost (the untranslatable Russian word for kitsch and banality) as a form of cultural legitimacy, she creates a serious genre out of a dissection of reactionary political discourse in Croatia in the 1990s that appropriated folk culture, music, literature, and art with the aim of justifying the waging of war and resuscitating some heroic, narcissistic form of history. There is something modernist about this gesture of Ugrešić’s—namely, protecting the integrity of high art against banality—but it comes from a self-reflexive ironizing postmodern author. I read this defense of high culture as a critical discourse that betrays an anxiety about the capacity of politicized mass spectacles to degrade cultural frames in wartime. (It is not simply an anxiety about art being swallowed up and made equivalent with the mass commodity form.) Though Ugrešić emerged from a generation of writers who pursued a poetic of self-reflexivity, she found a function for this type of aesthetic practice when engagement with the unfolding historical reality became a necessity.

University of Toronto

[1] Aleksandar Flaker, Proza u trapericama (Liber, 1983), 318.

[2] Aleš Erjavec, “Introduction,” in Erjavec, ed. Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition, Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition: Politicized Art under Late Socialism (University of California Press, 2003), 24.

[3] Ugrešić, Život je bajka: métaterxies (Samizdat B92, 2001), 129–30.

[4] Patrick Hyder Patterson, Bought and Sold: Living and Losing the Good Life in Socialist Yugoslavia (Cornell University Press, 2011), 1.

[5] Ugrešić, Život je bajka, 35–36, 51.

[6] Tatjana Pavlović, “Demystifying Nationalism: Dubravka Ugrešić and the Situation of the Writer in (Ex)Yugoslavia,” Postmodern Culture 5, no. 3 (May 1995), para. 11 of 13 (accessed 25 December 2016).

[7] Tania Modleski, “Femininity as Mas(s)querade: A Feminist Approach to Mass Culture,” in High Theory/Low Culture: Analysing Popular Television and Film, edited by Colin MacCabe (Manchester University Press, 1986), 38.

[8] Ugrešić, Štefica Cvek u raljama života (Samizdat B92, 2001), 54, 56.

[9] This reference was first noticed by Jasmina Lukić. See her “Trivial Romance as an Archetypal Genre: The Fiction of Dubravka Ugrešić,” Ženske studije, Women’s Studies Journal Selected Papers, Anniversary Issue 1992–2000 (no page numbers).

[10] Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth Century Literary Imagination (Yale University Press, 1979), 4.

[11] Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture and Postmodernism (Indiana University Press, 1986), 46, 47.