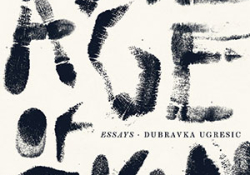

Fox by Dubravka Ugrešić

Rochester, New York. Open Letter. 2018. 308 pages.

Rochester, New York. Open Letter. 2018. 308 pages.

Neustadt Prize winner Dubravka Ugrešić’s latest historiographic metafiction bears her trademark erudition, wit, and nuanced cultural critiques. The fox—trickster, boundary-crosser, siren, and thus “the writer’s totem”—pervades its pages, but as Ugrešić highlights our struggle to survive, fox becomes “everyone’s totem.”

The narrator shares Ugrešić’s essay voice and much of her biography. Braiding fiction and history, she raises familiar questions: What is narrative? How do history and fiction differ as narratives (or do they)? How does high art relate to low, world to text, margins to centers? What makes us who we are?

Like Borges’s forking paths, the narrator’s tale meanders, its six parts marked by digression, disruption, and footnotes. Conflating the real and the imagined to problematize both, drawing epigraphs from Brodsky, Bulgakov, Nabokov, a fictional author, a Hollywood movie, and a Bulgarian folk song, Ugrešić’s globe-trotting novel investigates many of her trademark issues: the migrant’s plight, cultural commodification, the curse of nationalism, and the whitewashing of history.

In several sections marginal characters become central. The title of part 1, Pilnyak’s “A Story about How Stories Come to Be Written,” signals a major theme, while a treatise by I. Ferris, the imaginary widowed daughter of writer Doivber Levin, a real, but minor, Russian avant-gardist, supplies its epigraph, “The Magnificent Art of Translating Life into a Story and Vice Versa.” Drawn from the autobiography of a Russian bride whose Japanese husband transforms her life into art, Pilnyak’s actual tale masquerades as history. But the narrator’s research reveals that he “fills in” details and that literary historians don’t know if his characters existed, disrupting the categories of literature and history. Again, when part 2’s Widow shapes an imagined writer’s legacy, “a monument to him into which she inserted herself,” the narrator notes that “history, especially literary history,” creates illusions, like literature.

At the heart of Ugrešić’s labyrinth, the longest section, “The Devil’s Garden” (part 3), counters the intellectual riddles that come before and after with the immediacy of story. Longing for home, the narrator claims an inheritance in Croatia, a pretty cottage whose garden houses a fox. A male “intruder,” Bojan, has maintained the home and tried to tame the fox. From shared values and fresh-cooked eggs, “a deep metaphor for home,” an intimacy develops. After their first lovemaking, the narrator thinks: “home.”

But Bojan’s history literalizes Croatia’s lethal buried past. Ostracized for antinationalism, he de-mines in “The Devil’s Garden.” The two grow closer until Bojan, walking in a “safe” area, detonates a mine. The narrator then ponders the “trite metaphors” that convert life to art, declaring “our story . . . on the verge of soap opera.” Yet leaving the village for Europe after his death, she reflects, “In Kuruzovac—I now felt—I’d spent a goodly portion of my life yet I’d been there barely three weeks. . . . The world is a minefield and that’s the only home there is.”

Returning to puzzles, part 4 again juxtaposes fictive and real. Tracing the potential existence of a last novel by Doivber Levin—as his possible daughter, I. Ferris, claims in her imaginary treatise—the presumably reliable narrator finds evidence for this novel only in the memoirs of peers. She writes a footnote questioning witness reliability and, after Ferris’s reported death, deems her text, “whether real or fictional,” a “monument,” “a tombstone,” beneath which Ferris “buried herself.”

With its epigraph from Lolita, part 5, “Little Miss Footnote,” intensifies Ugrešić’s theme: “Human life is but a series of footnotes to a vast obscure unfinished manuscript.” Here we learn how librarian Dorothy Leuthold, who chauffeured the Nabokovs to California, “became an essential footnote to the history of modern literature,” the butterfly Nabokov named for her “her entry ticket to eternity.” In part 6, the narrator lectures at Scuola Holden, a real institution where students apparently learn that all texts are equal and everyone can tell stories. Mourning the “theatricalization of everything,” censuring the marriage of art and capitalism, new generic labels like creative nonfiction and twitterature, and devices like Rory’s Story Cube, she demands “some higher ‘truthfulness’” and reasserts the magic of literature.

As Fox convincingly demonstrates, “We are all footnotes, all of us in an unrelenting and desperate struggle . . . against vacuity.” In part 3, the narrator invokes Scheherazade, a fox whose stories bought her time, to underscore how narrative, comprised of fact and fiction, helps us resist the void. In her story about how stories come to be written, Ugrešić, another fox, has shaped a “truthfulness” that embodies the power of art.

Professor emerita at North Carolina A & T State University, Michele Levy has published on major Russian and European writers and, since 2000, on postcolonial and postimperial issues in Balkan culture.

Professor emerita at North Carolina A & T State University, Michele Levy has published on major Russian and European writers and, since 2000, on postcolonial and postimperial issues in Balkan culture.