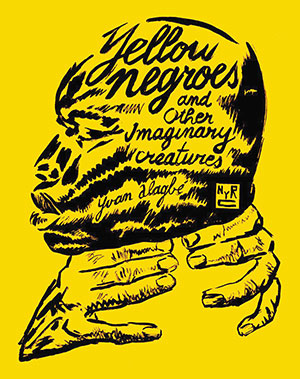

Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures by Yvan Alagbé

New York. New York Review Comics. 2018. 112 pages.

New York. New York Review Comics. 2018. 112 pages.

Comics have the unique capacity to create meaning between the verbal and visual as illustrations challenge and surprise the reader, but few comics capture the politics of the body and race as poignantly as Yvan Alagbé’s Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures.

A collection of Alagbé’s comics from 2004 to 2011, this is his first publication in English, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Rendered in all black-and-white brushwork, the dynamic narrative is emphasized and complicated through the illustrations, starting with the cover depicting a black man being choked by disembodied white hands. Many of the illustrations resemble deep woodcuts. Others are highly detailed historic scenes and cityscapes. All are hypnotically beautiful while often upsetting.

In the titular “Yellow Negroes,” an older white Algerian man, Mario, grows desperately attached to a younger black African man, Alain. Alain works to secure papers so he can work legally in France, and Mario holds this over his head in a perverse attempt to force his love. Mario’s behavior is inappropriate and unethical, but Alagbé allows for pity for Mario as he is consumed by guilt and loneliness borne of his nefarious role in the African colonial wars. Alain, in spite of everything, is also conflicted in his feelings, saying, “I sleep alongside him. My breath the breath of the victims. Loving or hating him, what does it matter? Pity tortures horror. Goodwill is attached to disgust like a rose climbing up my leg.” Alagbé deftly and articulately intertwines the body with the narrative, as colonialism continues to choke those trying to escape.

Alagbé captures the discomforting reality of the body, as it is simultaneously comforting and painful, familiar and alienating. As immigrants, black men and women, and refugees are persecuted and killed, Alagbé assumes the personal responsibility of not only remembering them but giving them a voice to accompany the body that allows them to live but evokes such hate. Alagbé concludes his work by saying, “Telling tales is the business of survivors. . . . Removed from myself, I remain alone on my lips. The lightness I once had I have no more. Can the world hold all of the woes of the world? Can my love?”

Claire Burrows

Austin, Texas