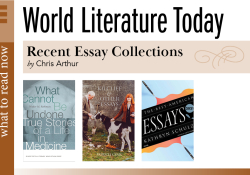

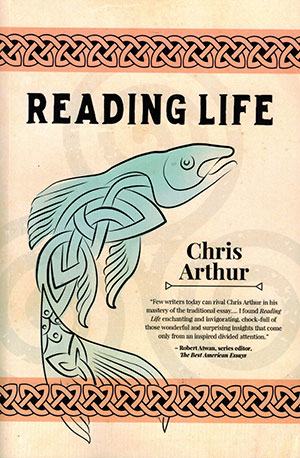

Reading Life by Chris Arthur

Mobile, Alabama. Negative Capability Press. 2017. 202 pages.

Mobile, Alabama. Negative Capability Press. 2017. 202 pages.

Chris Arthur knows what an essay is: an attempt to reach a further, transcendent understanding through writing. Chris Arthur’s 2017 collection of essays, Reading Life, keeps an eye to the particular while exploring perennial questions—on the one hand, his daughter’s feet, the contents of a bookshelf, words themselves; and on the other, our human condition, the violence of his Northern Ireland homeland during the Troubles, and the vastness of time itself.

In his essay “Priests (Reading fishing and desecration),” Arthur connects his early experiences growing up near Belfast during the rising and deadly sectarian/nationalist violence to the way that the word priest has evolved for him in the years since. Originally it was a word steeped in mystery and suspicion, and while most of that was stripped away by his experiences at university, Arthur admits to some lingering apprehension. Turning over his experiences in language leads him to a “general truth.” Arthur writes, “Words can continue to carry illicit cargoes long after we’ve ceased to be complicit in their smuggling.”

These essays often take a simple object and invest it with significance, such as the way a mechanical mile-counter mounted to a youth’s bicycle stands in for the click-click-click of our own mortality. Arthur suspects the indirect, analogical nature of the essay collection is met with discomfort by readers more familiar with fiction. His closing essay “Afterword (Reading essays)” offers both a justification for the form and some useful teaching in how to read the genre.

Though essay collections rarely outshine crime novels, biographies, or histories on the best-seller lists, readers who come across a collection such as Chris Arthur’s Reading Life know its value. Such a reader will probably know of the essay’s origin as I did, and so it was with bemused pleasure that I thumbed open Reading Life for the first time to find, right under my fingers, a quote from Montaigne’s “On Solitude.” These words from centuries ago, and Arthur’s reflection on them, came to me just when most needed.

I expect this book would offer such moments to anyone.

Greg Brown

Mercyhurst University