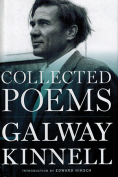

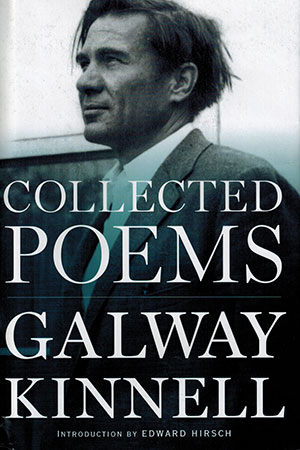

Collected Poems by Galway Kinnell

New York. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2017. 591 pages.

New York. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2017. 591 pages.

At nearly six hundred pages, this beautifully produced book is comprised of eleven sections of poetry (Galway Kinnell’s ten books and a section of his last finished poems not previously published in book form), an insightful nineteen-page introduction by Edward Hirsch that connects Kinnell’s evolving poetic style with developments in the poet’s thought and life, a biographical afterword, notes, and an index. One additional lovely feature is the inclusion of a photograph at the head of each section that is contemporaneous with the time of the original book publication. As did his friend and fellow poet, James Wright, Kinnell began by writing poetry in traditional accentual-syllabic lines, often with end-rhyme, but in time (as did Wright) he permitted himself to write in rhythmic free verse, influenced by Walt Whitman. To read this collection from the start is to experience the evolution of Kinnell’s understanding of poetic form but also to witness his unique voice and sensibility, essentially present from the earliest years.

Free-verse rhythms, however, were not the only influence of Whitman; Kinnell also sings the “body electric,” and he knows that the metaphysical is and must be experienced with—if not actually through—the physical. In many of his poems, we may feel that we are fully immersed in a description of something material (sometimes sexual), only to find ourselves pivoting in a moment to an instance of great emotional depth. Open this book to nearly any page and an instance will present itself.

This recognition of the importance of the body extends to the bodies of words themselves—namely, their existence in sound. In his midcareer, when he gave guest lectures on the music of poetry, Kinnell would bring a recording he had made of the sounds of various animals—crickets, frogs, birds, whales, wolves—and he would remark that all species with voices used rhythm to communicate with one another, along with other aspects of song. Kinnell loved the bodies of words, not just their denotations. In “Blackberry Eating,” we read: “the ripest berries / fall almost unbidden to my tongue, / as words sometimes do, certain peculiar words / like strengths or squinched, / many-lettered, one-syllable lumps, / which I squeeze, squinch open, and splurge well.”

Yet this is not the only side to Kinnell: he is equally fond of humor and wordplay, which too can suddenly pivot to the serious and emotionally resonant. If the material, the body, is the home of the spiritual, the body is not in itself that which is ultimately sought, though celebrated. In one poem of consolation, we read: “Forget about being emaciated. Think of the wren / and how little flesh is needed to make a song.” In other words, in poem after poem, even the ones seemingly abandoned to the sensual, we find a poet of remarkable depth and originality who finds in the corporeal world that which animates it and gives it meaning.

Kinnell is also importantly influenced by Rilke, especially his Duino Elegies, and like Rilke he bears witness to a world that wants to be seen by us and arise again in song. Of all the poets of his generation, Kinnell is likely the most sanguine and sane, the one most exuberantly in love with life—all of it, and he embraces it all to rise again in his poems. A brief quotation of Whitman serves as an epigram to his final book: “Tenderly—be not impatient, / (Strong is your hold O mortal flesh, / Strong is your hold O love.)” In the late poem “The Stone Table,” from his last book, Strong Is Your Hold, Kinnell writes: “I, who so often used to wish to float free / of earth, now with all my being want to stay,” and I suspect that he will stay, an undefeated spirit in the enduring body of his collected words.

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina