Juan Emar and the Gift of Being Unread

How do book reviews affect writers—for better, for worse, not at all? After receiving few and mostly bad reviews, Chilean author Juan Emar retreated to the countryside and wrote Umbral, his magnum opus.

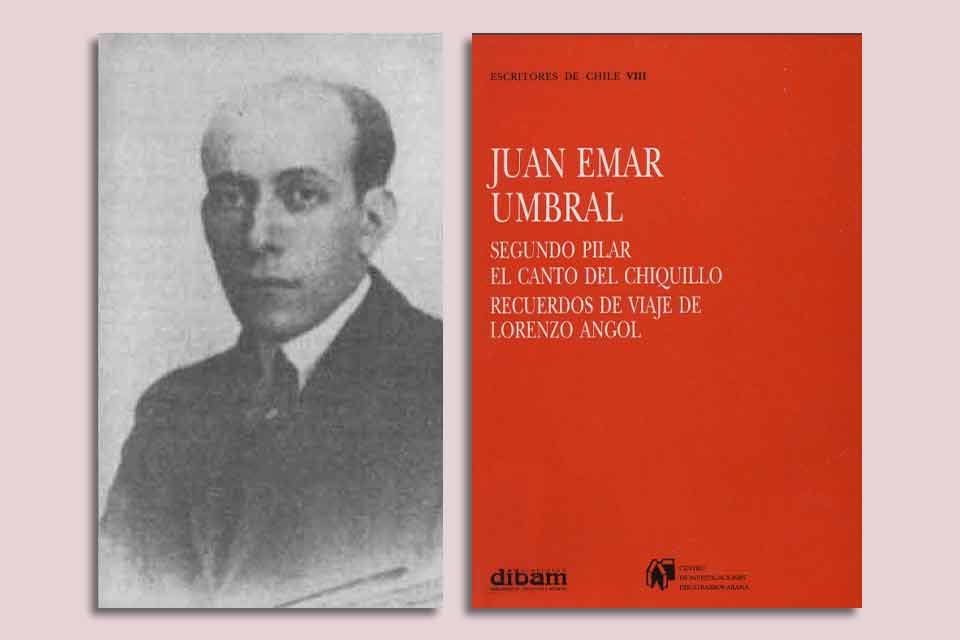

Few people outside of Chile have heard of Juan Emar (1893–1964). He has long been a cult author, secretive and reserved for a select few. Even in Chile, it seems that only now readers are starting to know him. The reasons are many, and they converge on a single point: Emar wrote a handful of strange, extravagant, and overly avant-garde books for his time, receiving few and mostly bad reviews. The leading critics of the time, such as Hernán Díaz Arrieta (also known as Alone) (1891–1984) and Raúl Silva Castro (1903–1970) ignored him. It’s likely they did not know what to make of such an unclassifiable and original author.

Juan Emar remains a secretive and difficult writer to this day.

Emar’s real name was Álvaro Yáñez Bianchi, also known as Pilo Yáñez, but he passed into literary history under the name of Juan Emar. By the late 1920s, he was already signing his press columns with this pseudonym, which is a play on the French phrase J’en ai marre, which means, colloquially, “I’ve had enough” or “I’m fed up.” The son of a wealthy family, he would end his days writing tirelessly, without ever holding a money-making job.

Despite the initial lack of good reviews and remaining largely unknown to many, it must be said that Juan Emar’s literary career is undeniably unique. Between 1935 and 1937, he published the three novels Un año, Ayer, and Miltín and the collection of short stories Diez, achieving no success with any of them. These were the years of social realism and regionalism in Chile, and the author’s metaphysical, playful, and experimental literature found no place in the country’s scant literary sphere. In 1942 he made the radical decision of withdrawing to the countryside in southern Chile to write his magnum opus, Umbral, a manuscript of more than four thousand pages. From that moment on, Juan Emar would never publish another book in his life.

The complete edition of Umbral was published posthumously in 1996. It consists of the five books (or “pillars”) titled El globo de cristal, El canto del chiquillo, San Agustín de Tango, Umbral, and Dintel. Although the complete edition was produced by the National Library of Chile, only the enthusiasm of his few loyal readers saved this massive work from oblivion. In his introduction to the 1996 edition, the scholar Carlos Piña lists Emar’s extravagant accomplishments, stating that

he wrote 4,134 pages, fell in love, truly or perhaps epistolarily, with 52 women, created 188 characters and a unique fictional town called San Agustín de Tango, and during his last years each of his sisters gave him 50 escudos a month so he could survive; 1,457 negative comments were made about him by close and distant relatives and family friends; he lived 26 years without publishing anything; he painted 213 paintings, most of which are now lost or forgotten.

It’s clear that by the early 1940s, Juan Emar had already grown tired of Chile’s literary circles and spent the next three decades building a new fictional world different from the one he had lived. This fictional work was, perhaps, exactly what its name—Umbral—suggests: a threshold, a paradoxical prelude to a greater, unknowable, and inaccessible project that attempted to decipher many mysteries of the world. In reference to this work, the Chilean writer Rafael Gumucio characterized the author in the following terms: “Everything in Emar suggests hidden secrets, esoteric rituals, initiations that never initiate anyone, because the writer and the reader are condemned, a condemnation that is also a reward, to remain at the threshold, glimpsing the mystery, the secret, but avoiding entering to not disturb it.” Perhaps it would have taken another four thousand pages to know what lay on the other side of the threshold created by Emar, and those pages, of course, were never written.

Juan Emar remains a secretive and difficult writer to this day. He avoided becoming a social writer or a man with a particular mission in Chilean literature or society. Perhaps that very idea bored him immensely. And what is certain is that nothing resembling success ever came to him. The Chilean author Alejandro Zambra rejects the idea of Emar as a forgotten writer, asking, “How can someone be forgotten if they were never truly remembered?” He has a point. Emar is a debt, and a difficult one to pay. Chilean narrative never quite absorbed him, and the reason may be historical. In twentieth-century Chilean literature, experimental fiction writers were almost nonexistent, and Emar may have been the only one. In 1971 Pablo Neruda wrote a prologue for a new edition of Diez, calling Emar “our Kafka.” The Chilean poet had read him carefully, and his closeness to surrealism made him a particularly fitting reader. “This precursor of us all, in his quiet delirium,” Neruda wrote, “left us as testimony a world quite alive, populated by unreality, which is always inseparable from what lasts the longest.” But Neruda’s praise did not help Emar become more widely read. In fact, Neruda was wrong because Emar was not really a Kafkaesque writer. His work does not delve into darkness, and his characters don’t seem to be tormented by life.

Today, Emar is the subject of writers whose fervent devotion to reading is rarely equaled.

Today, Emar is the subject of writers whose fervent devotion to reading is rarely equaled. The Argentine César Aira, another prolific author with over one hundred books, says Emar “has no precedents, no peers,” and Enrique Vila-Matas, a specialist in finding rare and suicidal writers, contends that “there was nothing strange about Emar. He wrote just to think.” In recent times, voices of praise have grown in number. Scholars might read and study him, but what has not changed is that the true readers of Umbral remain a small circle of initiates.

Juan Emar was the son of Eliodoro Yáñez, founder of La Nación, one of Chile’s most influential newspapers. Yáñez was also a senator and minister of the state as well as a successful businessman. His father’s wealth afforded Emar a privileged, cosmopolitan education. He lived in Paris twice during the 1920s, and it was later that, disenchanted and weary of the world around him, he withdrew from public life to write a book that only a tireless—and perhaps sleepless—writer could have created. He gained no financial reward from his writing, but Umbral might never have been conceived without the rejection and silence that greeted his first four books.

If Emar’s retreat was his way of confronting disillusionment in silence, then his success, in that sense, was complete.

University of Oklahoma