Persephone, Demeter, and Light from the Underworld: A Conversation with Poet Sarah McKinstry-Brown

With the recent publication of her latest verse collection, This Bright Darkness (Black Lawrence Press, 2019), poet Sarah McKinstry-Brown revisits the myth of Demeter and Persephone, the mother-daughter figures of Greek myth. We conducted the following exchange via email.

Daniel Simon: Many contemporary writers, like Angela Carter and Anne Carson, rewrite classical and popular literary tales, often to demythify them. What prompted you to rewrite the Demeter and Persephone myth from their points of view? How do you reclaim myth from the “marvelous lie” that it might become?

Daniel Simon: Many contemporary writers, like Angela Carter and Anne Carson, rewrite classical and popular literary tales, often to demythify them. What prompted you to rewrite the Demeter and Persephone myth from their points of view? How do you reclaim myth from the “marvelous lie” that it might become?

Sarah McKinstry-Brown: Because I am raising daughters in a culture that tells young girls and women that the simple fact of our bodies makes us vulnerable to acts of violence, I often describe the myth as “a container for my terror.” When my own daughters were small, my husband’s work for a local film crew saw him traveling the Midwest to cover national news stories, sometimes documenting young girls’ disappearances. Writing in the voices of Persephone, Demeter, and the Greek choruses allowed me to write through some of my deepest fears and anxieties while also tapping into my experiences as both a daughter and a mother. Exploring the rich complexities of the mother-daughter relationship coupled with images meant to echo and capture the reality of a sustained history of violence against women are what, I hope, allow me to reclaim this myth from the “marvelous lie” that has some interpretations of this story romanticizing Persephone’s abduction, rape, and return.

Simon: The chiaroscuro of the collection’s title, This Bright Darkness, anticipates so many of the binaries associated with the Persephone and Demeter myth: light/darkness, surface/depth, drought/fertility, death/rebirth. Yet you subvert readers’ expectations by starting the book proper with the “Return” section and ending with “Departure.” Was that an arc you imposed on the collection from the start, or did you discover it later on?

McKinstry-Brown: The opening poem in the collection, “Chorus: After 13 Months of Searching the Girl’s Body Is Found Five Miles from Our House,” is based on a true story about a little girl in our community who was abducted, raped, and murdered. Her body was eventually found in our neighborhood, and though this poem appeared in my first book, it was important to me to open my second book with that poem because the final lines capture the idea that there is a kind of beauty in her decomposition and how the earth reclaimed her body, releasing her, as the poem says, “from the body that caught his gaze.”

One of the first poems I wrote in the collection in Persephone’s voice, “Persephone, Stumbling into Morning,” is centered on what I found to be one of the most compelling ideas within the myth. I kept ruminating on the fact that Persephone, dragged to the underworld, held captive, and raped, is, upon her return to earth, greeted by an abundance of life and color. This world in bloom is an expression of her mother’s joy at her daughter’s return, and I saw this as another kind of violence inflicted upon Persephone. She’s been through hell, and now everything around her is overwhelmingly beautiful. In writing the opening lines for that poem, “It hurts. The sun. The salted air. / Those red flowers. Their swollen pistils,” I tapped into all the times in my own life when I was suffering and then stepped outside and found the birds mercilessly singing and the sun, shining.

In writing the opening lines for [“Persephone, Stumbling into Morning”], “It hurts. The sun. The salted air. / Those red flowers. Their swollen pistils,” I tapped into all the times in my own life when I was suffering and then stepped outside and found the birds mercilessly singing and the sun, shining.

As I wrote the book, I discovered that I was less interested in what happened to Persephone when she was in the underworld and more interested in how that trauma played out in her relationship with her mother, herself, and the world when she returned. I found myself preoccupied with how the trauma Persephone and her mother endured would inevitably alter their relationship, particularly since they both know Persephone is going to have to return to the underworld. In this context, mother and daughter are experiencing a kind of death of the world they once knew and are forced to rediscover each other and redefine their relationship. In “Demeter Preparing Her Daughter for Departure,” when it is time for Persephone to depart back to the underworld, Demeter laments, “This is a burden I don’t know how to shoulder. What mother is asked to watch her daughter die over and over?” Because I have two daughters of my own, I was haunted by this idea that Demeter would, with each change of the season, watch her daughter leave again and again. And yet, this is a fact of life, and the reality of parenthood. We’re raising our children to leave us, and, as they grow, our job is to, essentially, watch them disappear.

As I wrote the book, I discovered that I was less interested in what happened to Persephone when she was in the underworld and more interested in how that trauma played out in her relationship with her mother, herself, and the world when she returned. I found myself preoccupied with how the trauma Persephone and her mother endured would inevitably alter their relationship, particularly since they both know Persephone is going to have to return to the underworld. In this context, mother and daughter are experiencing a kind of death of the world they once knew and are forced to rediscover each other and redefine their relationship. In “Demeter Preparing Her Daughter for Departure,” when it is time for Persephone to depart back to the underworld, Demeter laments, “This is a burden I don’t know how to shoulder. What mother is asked to watch her daughter die over and over?” Because I have two daughters of my own, I was haunted by this idea that Demeter would, with each change of the season, watch her daughter leave again and again. And yet, this is a fact of life, and the reality of parenthood. We’re raising our children to leave us, and, as they grow, our job is to, essentially, watch them disappear.

Simon: The choric figures scattered throughout the book (flowers, newscasters, mothers, grandmothers) are gathered into the powerful final poem, “The Searchers,” which, coming full circle, brings us back to the opening poem (“After 13 Months of Searching . . .”). My sense is that readers are invited to participate as members of the chorus in these poems—we cannot look away or pretend to be separate from the social fabric torn apart by the young girl’s rape and murder. What role do you envision the reader playing in the poems?

McKinstry-Brown: It was important for me to bring the collective “we” into the book so that readers feel they are part of a story that has, since the beginning of time, repeated itself across cultures. Because the poems in this collection are primarily rooted in ancient Greece, the choral poems are meant to startle my readers back into this world, weaving them into the narrative to signal that, yes, we are collectively responsible for and traumatized by a culture of violence, and, yes, no matter the time or the place we’re living in, it remains particularly dangerous to bear and love and raise our daughters in a world where the fact of their bodies makes them vulnerable to violence.

Simon: So many of the classic story arcs—the quest, overcoming the monster, rebirth—involve some redemptive moment at the end. Again in “The Searchers,” which serves as your book’s epilogue, one sees the “chorus of birds . . . lifting” in the final stanzas. Yet the subject of the poem—the search for the girl’s body—still haunts us. Is there redemption at the end? Between what happens and the telling of it, is that “our only currency”?

McKinstry-Brown: I don’t know that there’s redemption at the end. Ending the book on the discovery of a girl’s body and opening the book with the discovery of a girl’s body was my signal to my readers that, unless our culture undergoes some profound changes, this narrative is going to play out again and again. The end poem is actually a prologue to the opening poem, and I wanted the reader to feel trapped in that cyclical structure of the book.

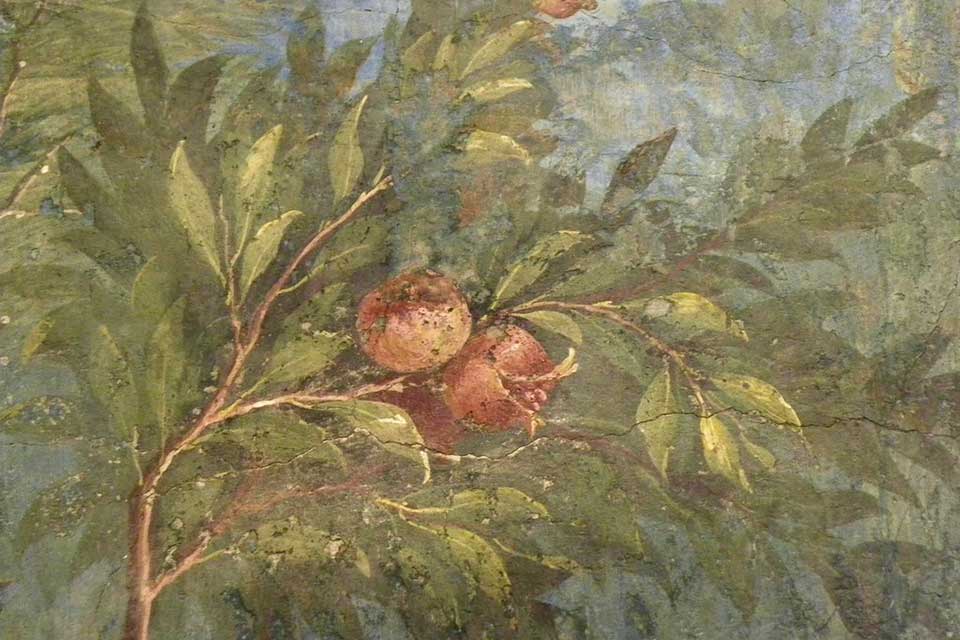

In the poem “Persephone Writes Her Mother,” Persephone explains to her mother why she decided to knowingly eat the pomegranate seeds that would bind her to the underworld. She reveals that she’s pregnant with Hades’ child and needs to find a way to create some agency in her own life. Persephone knows that the only way to reclaim her power in the situation is to accept her fate as Hades’ queen. Though it may seem like a bit of a leap, there’s a moment from the poem that echoed in my mind during the Brett Kavanaugh hearings. This man, accused of sexual assault, is now holding one of the highest positions in the land. Persephone tries to articulate the bind she’s in and asks Demeter, “What if the hand that pushes us into the fire is the same one that picks us up when we fall? Oh mother. What choice is there when we have none at all?”

Never mind the fact that this myth is thousands of years old; much of what it can teach us about the fate of women in this world is still relevant. We live in a world where men hold most of the economic and political power—I see it every day in my own personal and professional life, the men who metaphorically push us into fires to try to destroy us are often the only ones who have the power to pull us out of that particular hell. And, yes, I do believe that this “telling” is our only currency. Women have always shared their stories of trauma with each other, but with the #MeToo movement, we’re beginning to share those stories with the men in our lives and with our sons and daughters.

Simon: And that “Summer” idyll in the middle of the book, after Persephone returns home, has its dark moments too: Demeter not quite able to let go of her grief, the “knife’s tip” of Persephone’s words, Persephone resisting the mythical version of herself (i.e., the stories others tell about her), the “coming winter” even as the sun rises and “The story / begins again.” For the grandmothers, this is the “season of unraveling.” Even knowing “how this must end,” what about summer did you want to convey in this central section?

McKinstry-Brown: I wanted the summer section to act as a kind of reckoning for both Persephone and Demeter. I wanted summer to be the time and place where Persephone begins to work through the power of her own sexuality, and in the midst of this, I wanted Demeter to be faced with her own powerlessness. There are many poems in this section where Persephone is discovering that in order for her to survive the trauma she’s been through, she has to make meaning from it. Many of the poems are about her struggling to redefine herself on her own terms so that she’s not defined by her mother’s grief or others’ pity; she wants to take ownership of her story. She wants agency in her life.

Any woman who’s been painted in a particular way or who has been subject to the kind of gross oversimplification of her story or her identity knows how taxing and suffocating it can be to be only viewed through the lens of “Madonna” or “whore” or “victim” or “survivor.” There’s a line from “Persephone Lets the Blind Beggar Read Her Palm” where she says, “My heart was not built to carry. His want. Her sorrow.” Persephone is resisting her own mythology, while Demeter, once a powerful goddess, is learning how little control she has over her daughter’s fate. Summertime, when everything is wild and messy and in bloom, felt like the perfect reflection of the messiness that mother and daughter are experiencing as they’re forced to redefine themselves and their relationship as a result of the trauma they’ve both endured.

Simon: You’ve lived with this story for over a decade, haven’t you? During this time, as your own daughters have grown, has a certain generational wisdom given you the strength to return to this particular tragedy over and over? You acknowledge your parents for showing you “how to love the world and find the music within it.”

I am an expert in the field of my own heart, and having daughters has deepened my understanding of the beauty, the terror, and the fragility of the human experience.

McKinstry-Brown: Recently I gave a reading at my university, and during the Q&A someone asked me about what sparked my interest in this myth. I admitted that there were times when I was writing the book when I’d become anxious about a particular detail because I worried my lack of knowledge about ancient Greece would mean that some Greek scholar would read my book and “out” me as a fraud. But the longer I worked on the book, the more I discovered that the reason we all latch onto myths and fairy tales and the stories of our grandparents and our parents is because these are our creation stories, and, as such, they are our earliest teachers. Myths are timeless and they belong to all of us, and the structure of this particular myth allowed me to pour my own wisdom and experiences as both a mother and a daughter into each poem. As I told the audience I read to that night, “I may not be a Greek scholar, but I do have a PhD in being a mother, a daughter, and in what it means to be a woman in this world in this body.” I am an expert in the field of my own heart, and having daughters has deepened my understanding of the beauty, the terror, and the fragility of the human experience.

Poems are all about making music with our words, and I truly believe my father’s love of music, my mother’s empathy, and my own imagination are what led me to poetry.

When I was pregnant with my first daughter and people were trying to prepare me for what was to come, everyone talked about how deeply I’d love them, but no one articulated how terrifying it would be to bring a new life into a world that’s as horrible as it is beautiful, as bright as it is dark. As a mother myself, I now have a deeper appreciation for my own mother and father and their role in my own creation story, the mythology around how I became a poet. I wanted to honor my mother in this book because she is the most compassionate, empathetic, capable person I know, and she truly taught me how to love the world, in spite of its ugliness. And I wanted to honor my father because the only thing he loved as much as he loved me was music, and when I was with him we were always surrounded by music; poems are all about making music with our words, and I truly believe my father’s love of music, my mother’s empathy, and my own imagination are what led me to poetry.

Simon: In your acknowledgments to the book, you thank Carolyn Forché for the enabling gift of a line from her poem “The Memory of Elena”: “bells / waiting with their tongues cut out / for this particular silence.” In a remarkable three-part interview that Forché granted to Chard deNiord for WLT, Forché discusses the idea of “sacred radiance” in the language of witness, writing that “Language written in the aftermath of extremity bears the imprint of that experience, regardless of its content; it is that which is written out of that which was endured. In many respects, this is ineffable. The words come not from recollection in tranquility but from wanderings in a debris field.” In choosing to embody the “tongue cut out” of a young girl in this book, how has the “imprint” of that experience changed you?

When we are afraid to speak, when we are told to be quiet, when we feel as if we don’t have a voice, when we, or the people around us, use words to cover the truth instead of laying it bare, and when women feel as if they have to silence or bury or kill some part of themselves in order to stay alive and thrive in this world, then humanity collectively suffers.

McKinstry-Brown: When I read Forché’s collection about the atrocities occurring in El Salvador during the civil war, the image of bells with their tongues cut out resonated so deeply within me because even at a very young age, I’ve always been aware of how dangerous and ugly silence is. When we are afraid to speak, when we are told to be quiet, when we feel as if we don’t have a voice, when we, or the people around us, use words to cover the truth instead of laying it bare, and when women feel as if they have to silence or bury or kill some part of themselves in order to stay alive and thrive in this world, then humanity collectively suffers. In this way I do believe that, as Demeter says in “Last Days of Summer: Demeter Insists the Chorus Spread Persephone’s Story,” “telling is our only currency,” and I do believe that whether it’s through a poem, a story, a shared glance, or a conversation, when we speak truth to power and to each other, then we can fulfill Demeter’s promise that “What is lost can be found” and “The earth will, again green, soften.”

April 2019