Shining a Light on Neglected History: A Conversation with Shelly Sanders

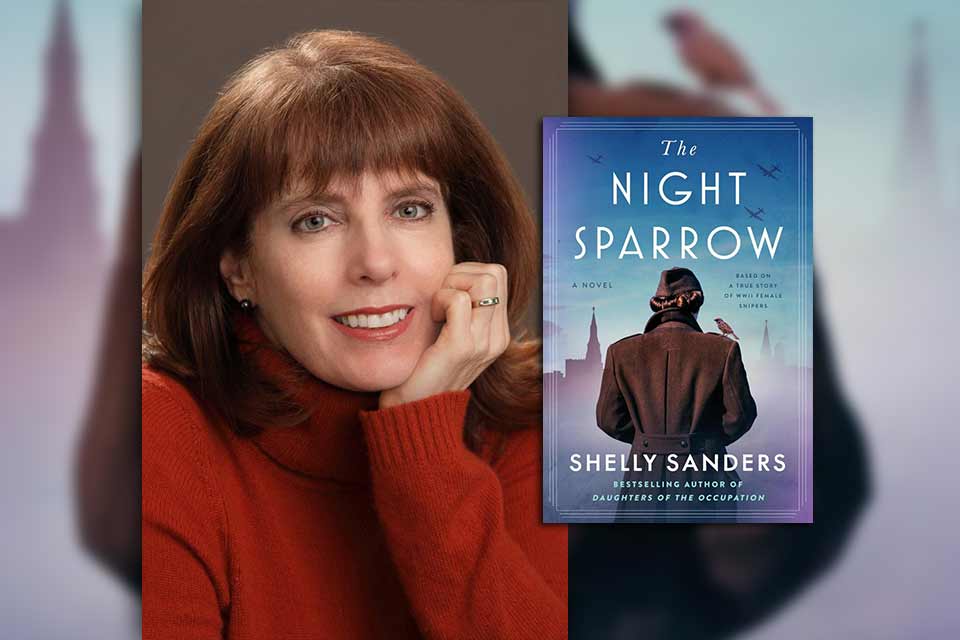

Shelly Sanders is a Canadian novelist who writes historical fiction set in Old Shanghai and the former Soviet Union. Her main characters are Jewish and ultimately have to flee their homes in the hope of finding safer shores. Her latest novel, The Night Sparrow, is a harrowing tale of female snipers in the Soviet Red Army during World War II. Based on real people in a real sniper-training school, The Night Sparrow’s characters are ultimately sent to Berlin to capture Hitler. I know Shelly through our work on the board of Artists Against Antisemitism but first got to know her writing when I read her previous novel, Daughters of the Occupation, a little-known Holocaust story set in Riga. She’s also the author of the young adult trilogy Rachel’s Secret, Rachel’s Promise, and Rachel’s Hope, two of which take place in Old Shanghai, a setting very close to my heart. Over email, I discussed with Shelly her new novel, her writing inspirations, and her thoughts on why history matters.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Congratulations on your new novel! I knew nothing about the female snipers in the Red Army during World War II. How did you come across this story in the first place, and when did you decide you had to write about this history?

Shelly Sanders: My editor at HarperCollins urged me to write another historical fiction, set in World War II, after the success of Daughters of the Occupation. I was excited about this prospect, as long as I could find a never-before-told story about unsung women. It had to be set in the Soviet Union, the only country in World War II with women in combat. Very little has been written about the Eastern Front during World War II, where the Red Army (our ally at the time) fought vicious battles against fascism. Moreover, my maternal roots go back to the late 1700s in Latvia (occupied by the Soviet Union from 1944 to 1991). My female ancestors’ lives were rife with trauma, and I’ve become obsessed with the history that shaped them.

The seed that implanted The Night Sparrow was the Central Women’s Sniper Training School, which I discovered after a week of research. I remember getting a chill down my neck as I started reading about this first-ever school for female snipers. As I came upon names, triumphs, and losses, I wondered why I’d never heard about these courageous women. The more I learned, the more determined I became to write a novel that authentically reflected these heroic female snipers erased from the historical narrative.

I remember getting a chill down my neck as I started reading about this first-ever school for female snipers.

Blumberg-Kason: I’m so grateful that publishers have decided it’s way overdue to tell these stories of women in history who contributed so much yet have not been recognized until very recently. One of the other pieces of history I didn’t know until I read The Night Sparrow was that Stalin didn’t want the women snipers to talk about their work even after the war had ended. He had no such stipulation for men. Thank goodness for the female snipers who did write about their experience. You reference these books in your bibliography and author’s note. What surprised you the most about their stories once you started your research?

Sanders: I was fortunate to get my hands on several illicit diaries kept by the female snipers that had been translated into English. Thank goodness they defied orders forbidding them from writing about their experiences! Their moving, candid words revealed the jarring conflicts they faced on the front, as teenagers and young women, who had to balance their burning desire to defend the Motherland (fueled by propaganda they’d experienced since birth) with their innate and naïve yearning for love. Roza Shanina, an eighteen-year-old kindergarten teacher when she joined the Red Army, doesn’t mince words: “A fellow from 215th made me an offer—perfume or anything I might like, but I am not for sale. . . . I find it so much harder to make friends here with sniper girls. Their jealousy and envy are pitiful. Girls shall be girls no matter how many rifles they carry.”

I read diaries kept by male snipers as well, which sharpened the contrast between the genders, with men writing primarily about battles and daily conditions while the women focused more on their emotions, relationships between their comrades, and, for many, the despicable way they were treated by their male superiors.

Blumberg-Kason: As a fellow history buff, I can’t tell you how much I appreciate the nuance and complexity you include in The Night Sparrow. I worry that history has been narrowed down to a conflict of good vs. evil, and it’s become very difficult to see gray areas. The scenario I’m thinking about is when the Red Army fought against the Nazis in your book and Elena, your protagonist, witnessed horrible atrocities at the hands of her male compatriots in the Red Army. The Soviet Union was on the side of the Allies, yet their soldiers committed so much sexual violence and other atrocities.

In the history I learned in school, the Allies were all-powerful and good. I’m glad you show that history is often messy. More specific to your book, as the main character Elena is becoming an accomplished sniper, she is taken advantage of by a male soldier in her unit who assumes she’ll be a “frontline wife.” When in your writing process for this book did you decide to include these instances of sexual harassment and assault? Was it something you wanted to include from the beginning, or did you stumble upon these stories of “frontline wives” in your research?

Sanders: Until I began doing research for this novel, everything I knew about combat was from a male perspective. The female voice has been sorely neglected, ironically, from the Soviet Union, where women entered combat before females in any other country.

I came upon the term “frontline wives” in academic papers I read about Red Army women. Many female snipers were interviewed by the Mints Commission, created and led by historian Isaak Mints, to document personal experiences of both combatants and civilians during the “Great Patriotic War.” After I’d read a few accounts of female snipers being raped and/or becoming a superior’s sexual slave, I knew I had to include this untoward depiction of the Red Army’s treatment of women. This is an integral part of their story, along with their oversized men’s uniforms and difficulty in coming to terms with taking lives, which is contrary to their intuitive, maternal role as givers of life.

Blumberg-Kason: Another part of The Night Sparrow that is complex and perhaps new to some readers is the conflict that arises between Elena and Chava. They are in the same battalion and work well together but have very different ideas of the Soviet Union. Chava is a patriot and believes communism has brought equality to everyone in the Soviet Union. Elena doesn’t agree and thinks Stalin is allowing anti-Semitism to fester all while promoting equality. Elena feels she’s unsafe both in Germany, where she’s fighting the enemy, and back home in the Soviet Union, where people look down on her because she’s Jewish. This is just one example of the horseshoe theory, where the extremes of the political spectrum—the far right and the far left—are basically indistinguishable when it comes to anti-Semitism. Again, when in your writing process did you know you were going to going to include this part of the story?

Sanders: To bring authenticity to Elena’s character and to better understand the Soviet Jewish experience during World War II, I needed to grasp the interiority of Jews from Minsk. Since religion was essentially banned at the time, being Jewish was not something that could be easily defined, and it varied between the city, countryside, and families. I read a number of books with personal recollections and was struck by the varying perspectives. Some young people had a good sense of what it meant to be Jewish from older relatives who’d passed on their traditions and knowledge, while others had no idea at all what Judaism was, other than an unwanted label identifying them as “other” or “less than.”

When I came across a family where the parents were divided—the father had forsaken his Judaism for communism, while the mother was devoted to her clandestine Jewish identity—my interest was piqued. I wanted to explore the impact of a mixed-identity marriage on children and made the mother the communist and the father the faithful Jew in The Night Sparrow.

In truth, I didn’t know how Elena would cope with her complex family dynamics. As the narrative unfolds and she encounters the extermination of Jews by bullets, her past familial relationships and her current bonds with non-Jewish female snipers collide. I didn’t know how she’d feel or react until I began writing this scene. Her character informed the plot, and the plot shaped the character. This is one of the most rewarding facets of writing, seeing characters evolve, following their lead.

This is one of the most rewarding facets of writing, seeing characters evolve, following their lead.

Blumberg-Kason: I want to step back to earlier in your writing career when you published a young adult trilogy with Second Story Press in Canada. You wrote about Jews in Shanghai a hundred years ago, which is based on your family’s history. Can you talk a little about your family’s story escaping Russia for Shanghai and if and how it inspired you to start writing in the first place? Also, are you planning to write about Shanghai for an adult audience?

Sanders: The only grandparent I knew was my maternal grandmother, Shelly (Rachel) Talan, who died when I was thirteen. She was from Russia, had a thick accent, embroidered shirts for us as gifts, and was not one for hugs. After my first child was born, I visited my grandmother’s older sister, Nucia, in Montreal. With great reluctance, she told me about their childhood in Novo-Nikolaevsk (Novosibirsk), Siberia. Their village was set on fire one night. They fled, taking the Trans-Siberian to Vladivostok and then a boat to Shanghai, which took Jews without papers.

My great-grandmother made rag dolls to earn money, and my grandmother attended high school. I listened, rapt, as Nucia described the challenges they faced, like typhoons and a completely different culture. Over the next several years, I worked as a journalist and read everything I could find on Russian pogroms and Jews in Shanghai. When I came upon the little-known 1903 Kishinev pogrom, the idea for a novel began to percolate in my mind. Although this event predated my grandmother’s, it was historically significant as the first major pogrom of the twentieth century, and it was ignited by the publisher of the daily newspaper, who printed false, inflammatory headlines about Jews.

I have been considering the idea of an adult novel set in Shanghai during World War II, inspired by my grandmother’s younger brother, Monya (Moses) Talan, a member of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps. Monya was a bona fide hero, awarded the British Empire Medal for his role in bombing German ships in Goa, and for leading the deposed Chinese president, Chiang Kai-shek, through Japanese-occupied territory to safety.

This would be a significant departure for me, an author who writes about unsung women who’ve changed history. Perhaps I should consider adding a female character and weaving her story through the narrative.

Blumberg-Kason: It sounds like you have a novel there just waiting to be written! I still think these stories from Old Shanghai are not as commonplace as they could be, and just the concept of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps seems foreign, so to speak. Its units included members from around the world. Maybe you could fictionalize a character based on your grandmother as she works alongside Monya?

Continuing with the idea of future projects, your previous book, Daughters of the Occupation, is set during World War II in Riga, which isn’t one of the more known settings of the Holocaust. The Night Sparrow also tells a little-known World War II story. Do you have other ideas for more stories to uncover during the war? And can you talk about what you’re working on next?

Sanders: Shining a light on neglected historical events and people has been my underlying focus since my first novel, Rachel’s Secret, which Kirkus called “critical for its underexplored subject.” Daughters of the Occupation delves into the nearly unknown Rumbula massacre, while The Night Sparrow shines a light on unsung female snipers erased from the historical canon. Now, I’ve been commissioned by HarperCollins US and Canada to write about a World War II Red Army women’s regiment of combat pilots, to be published in 2027. These female pilots have captivated me with their skills and courage as well as their often amusing determination to retain their femininity while bombing the Germans.

For my next historical fiction, in addition to the one I referenced about my uncle, I’d love to write a novel inspired by Helene Khatskels, a member of the Jewish Labor Bund in 1904. Under the code name “Rachel,” she smuggled socialist books in tsarist Russia, took part in other secretive tasks, and was eventually arrested.

I’d love to write a novel inspired by Helene Khatskels, a member of the Jewish Labor Bund in 1904.

I also have a writing residency in November, in Latvia, to work on a nonfiction I’ve been researching for more than a decade. Informed by the discovery of my furtive Latvian Jewish roots, it explores the intersection of ancestral trauma and estrangement. The working title is Rooted in Silence: A Memoir of Intergenerational Secrets and Trauma.

Blumberg-Kason: These are such exciting book projects, and I will be first in line for your combat pilot novel in two years! It’s fascinating that you write for a publisher in both the US and Canada. As a Canadian writer, do you see many differences between publishing in Canada and in the US? For instance, I noticed your cover for Daughters of the Occupation is different in the Canada and US markets, but The Night Sparrow cover is the same. How does it work with selling a book in both Canada and the US?

Sanders: I’ve been fortunate to be published by HarperCollins US and Canada for my past two novels, and will be again for my next one. Since it’s the same publisher, the editors have worked closely on my manuscripts, providing me with one clear set of revisions, and the books are published with US spellings because it’s more cost-effective than printing two separate versions. I have two contracts, publicists in both countries, and different launch dates. In Canada, both novels have been national best-sellers, but in the US, with its exponentially larger population and the greater number of books published, best-seller status is a major challenge.

For Daughters of the Occupation, HarperCollins Canada created their cover first, as it was released here before the US edition. Harper Perennial decided to change the cover slightly, which is common when a book is published in different countries.

The Night Sparrow cover underwent several variations, beginning in Canada with the female holding a sniper rifle, but a more subtle color palette. The US office removed the rifle because many stores won’t sell books with guns on the cover, added the brighter hues, and this became the cover for both countries.

Blumberg-Kason: Now for a few short questions about your reading tastes! What’s the last good book you read?

Sanders: Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, by Svetlana Alexievich. I read her Nobel Prize–winning book, The Unwomanly Face of War, while researching The Night Sparrow and became enthralled by her collection of oral testimonies. In Secondhand Time, she has created not just a recollection of history but a communal, haunting voice, a real sense of the people and how their lives were upended by the economic and political reforms in Russia during perestroika.

Blumberg-Kason: What is your favorite genre after historical fiction?

Sanders: I adore short stories and love listening to authors reading their work on the New Yorker podcast.

Blumberg-Kason: Which books are on your to-be-read pile?

Sanders: I’ve almost finished A Bigamist’s Daughter, by Alice McDermott, an older novel (1982) that I somehow missed. It’s a beautiful read. Then, Mother Doll, by Katya Apekina, is at the top of my pile, followed by Life and Art, a book of essays by Richard Russo; The Red House, by Mary Morris; Memorial Days, by Geraldine Brooks; and The Enchanted Wanderer, by Nikolai Leskov, short stories translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky.

Blumberg-Kason: I’m now adding more books to my to-be-read list, although I have read and loved Mother Doll. Thank you so much for discussing your work and your important contributions to historical fiction!