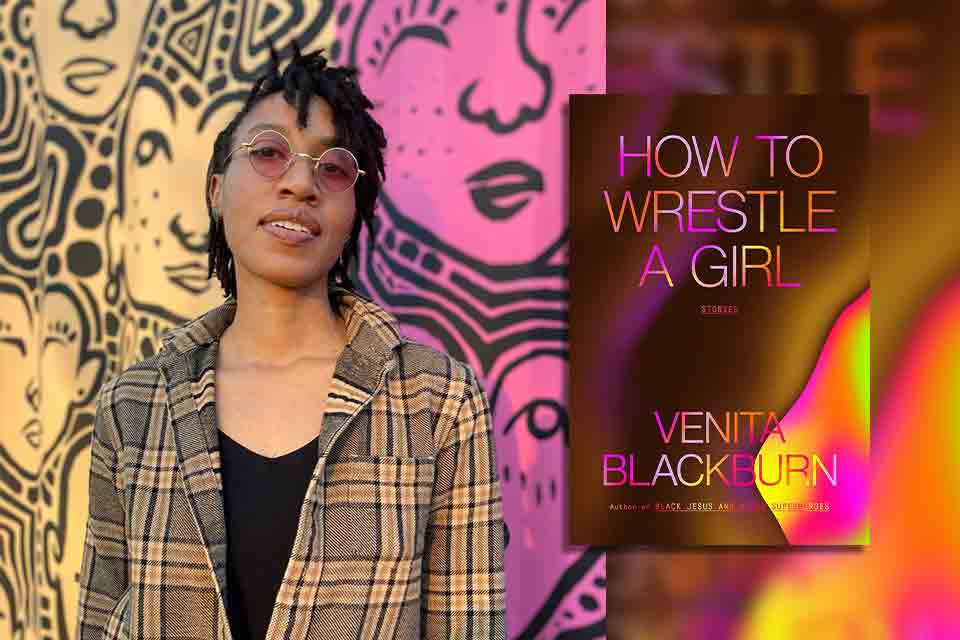

Writing for Yourself First: A Conversation with Venita Blackburn

Venita Blackburn is a faculty member in the creative writing program at California State University, Fresno, and the founder and president of the Live, Write workshop, an organization devoted to offering free creative writing workshops for communities of color. Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including the Paris Review, New Yorker, American Short Fiction, and Bellevue Literary Review. She was a 2014 Bread Loaf Fellowship recipient and has received several Pushcart Prize nominations for her work.

Her short-story collection Black Jesus and Other Superheroes won the 2016 Prairie Schooner Book Prize and was a finalist for the 2018 Young Lions Fiction Award and the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. She was recently longlisted for the 2022 Joyce Carol Oates Prize for her recently released How to Wrestle a Girl: Stories (MCD/FSG Books, 2021), which was also notably a Paris Review Staff Pick and an Amazon Editors’ Pick as well as a finalist for the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence.

Hunter Liguore: How did you get started with writing? What was your early inspiration, a moment that you can point to as the starting point?

Venita Blackburn: When I was in middle school, I wrote a weird emo poem and put some artwork on it for class. My mom thought it was interesting and took it to work and showed everyone. She said they were impressed. :) I remember that moment changing my perspective about being a writer and writing. I certainly didn’t decide to be a professional writer at that moment at all. In fact, I worked actively against being a writer for the next ten years, but I remember recognizing a kind of relationship with the world that was possible through my writing. It wasn’t something to do for a grade and walk away; it was something that could reach to unseen and unnamed places, and that was exciting. I’m grateful for that experience and reception because I became unafraid to share things I wrote. I’m also fortunate because it could’ve gone quite the opposite, lol.

Liguore: In what ways did growing up in Compton, California, set the stage or influence your writing life? Any eccentric elements about your homelife or childhood to share?

Blackburn: The Compton I grew up in wasn’t the one I think a lot of people think about from movies. Yes, there were gangs and poverty, but it’s mostly a working-class suburb with families living their lives. Yes, gun violence and police brutality touched my family, but I remember most the gender discrepancies and what I thought were unfair treatments of me because I wasn’t allowed to play outside like the boys. There was an air of danger presented to me about the outside world around me specifically because I was a girl. That was weird and unjust to me then and, looking back, probably reasonable. That pressure on girlhood definitely shaped my self-realization and choice of content as an artist. There’s also this new romanticizing of Compton because some extremely successful people have come out of the city when it has such a violent reputation. I’m all for it, ha! The world loves an underdog story. I do too.

Liguore: Who were some of your early influences? Any early mentors that made an impact/impression? Any books/media/history that influenced your writing life?

Blackburn: My mother was my biggest influencer for sure; she cultivated a love of learning and self-education. I always mention the greats, Toni Morrison and James Baldwin, as literary gurus for me, not just for the work they produced in fiction but also for their philosophy of the world and the profound grace by which they spoke and lived. Of course, they were often the smartest people in the room. Because they were also Black in a racially immature civilization, they were often met with astonishment at the audacity of their talent and their extraordinary awareness of it all. I call that a master class in how to just be.

I also watch a lot of cartoons, and I am not ashamed. There’s something limitless about the imagination in the realm of animation that I think encourages me to seek more unorthodox shapes in my stories and characters. The queerer the cartoon the better these days.

There’s something limitless about the imagination in the realm of animation that I think encourages me to seek more unorthodox shapes in my stories and characters.

Liguore: Do you have a memory to share of the “deciding moment” when you chose or decided upon writing as a career option: the moment you knew there was no backing out, so to speak?

Blackburn: I quit my retail management job when I was twenty-one and went to grad school for creative writing. The real world seemed like a total scam. I figured I could write, be poor, and be happy rather than work a normal job, have money, and be miserable. Weirdly enough, money is not off-limits to writers as I thought or was led to believe. I remember as an undergrad the administrators saying that artists won’t make as much early but will catch up later. There’s some truth to that.

Liguore: Can you share a little about your early publishing? What was the first story you published, and how did that impact your writing path going forward? Any successes or difficulties you can share with readers?

Blackburn: Oh, my first story went out to a journal that probably doesn’t exist anymore. I would just submit without knowing which journals were considered more reputable or anything. I didn’t have the full traditional perspective about the publishing world. I even published my first book all backward, really. I didn’t have an agent or try to go through traditional houses. I just did the slush pile system and tried a contest. I happened to win it, which was a surprise.

Technically, I’m probably a fast writer, but my first book took about eight years from first story to final publication. I was writing through a recession, the death of my mother, layoffs from work, and a sick father for that book. The writing was such a salve to all the wounds. I developed my own philosophy about writing for myself first during that time, and I keep it now. I don’t write to publish, to entertain or educate the world. I write for understanding and for the entertainment of myself first. After that comes understanding by the larger communities around me.

Liguore: Describe any major shifts in your life that may have altered the course of your writing life. Were there other career paths available? How did writing win out?

Blackburn: I wanted to be an entrepreneur or doctor or astronaut. Astronauts are still sexy but not the greatest poets, lol. Actually, being a teacher and loving it really made writing work. The two professions align well.

Liguore: Your short-story collection Black Jesus and Other Superheroes won the 2016 Prairie Schooner Book Prize and was a finalist for the 2018 Young Lions Fiction Award and the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. Can you share your process for selecting the stories that grew into the collection? Were there others you considered including and didn’t?

Blackburn: The stories for that collection were written over several years, and some things I’d written definitely didn’t make it into the collection, not necessarily because they hadn’t been published. I did have a certain thematic idea for the collection surrounding special abilities/disabilities/perspectives that are extraordinary in an ordinary world and not necessarily very helpful in a practical sense. I’m fascinated with people that are burdened by superpowers rather than freed by them. Stories that didn’t fit for whatever reason didn’t make it.

I’m fascinated with people that are burdened by superpowers rather than freed by them.

Liguore: Can you share a little about the inspiration for the title story, “Black Jesus”? What was a challenge you faced when writing it, if any?

Blackburn: That one is around ten years old now. I’m not sure exactly what I was thinking, but I do know it fits my brand of questioning all instructions given even if they are supposedly divine. I grew up Southern Baptist in mostly Black communities, so religious iconography that featured racially appropriate material was common and intriguing. That along with a character sitting between generational expectations made sense to explore.

Liguore: What story from the collection are you most proud of (or most happy with its reception, or seeing it in print) and why?

Blackburn: I really like “Brim” now. It’s one of the longer stories, and I tend to gravitate to my flash fiction pieces more often because they’re fun to read for audiences. “Brim” is special because I got to write a little outside of myself, a male perspective, a disabled person. I am an advocate for writing the other if you’re careful and honor that, utilizing experiences you know well as an entry point.

I am an advocate for writing the other if you’re careful and honor that, utilizing experiences you know well as an entry point.

Liguore: As a reader, every page is a new discovery. In fact, as I turned the pages, I realized I couldn’t predict what came next and was surprised, time and time again, with what I found. At an early point, I realized I was reading a work of genius, by someone who didn’t just write stories but actually imbued an entire world onto the page—and in a way that seems effortless. Did you have moments where you questioned your writing, or the story, and if so, what can you share with writers about the steps you took to overcome any obstacles? What kept you writing?

Blackburn: I mean . . . thank you! Am I a genius? I don’t know. Maybe. Lol! It’s not important. I’ve said this many times; I am profoundly in love with humanity even as I personally debate whether efforts to save us from ourselves are really a good idea. I kind of always knew I’d get a book into the world. There was so much going on that I didn’t really have time to think that there would be a second book or a third. There are always surprises that come with sharing work and engaging with the vast world. It is a ride. No matter what happened with publication, though, I would always write. I still write. I write more that is never seen—that is because I journal so much. I often journal ideas that become stories. The writing is not a problem for me. Finding time to write the big books is a little challenging with teaching, but I’m getting the hang of balancing that. You have to love the art and shut out the rest until it’s time.

I am profoundly in love with humanity even as I personally debate whether efforts to save us from ourselves are really a good idea.

Liguore: Your second collection, How to Wrestle a Girl: Stories (2021), is its own work of art: stories intermingled with crosswords and grief charts, a seamlessly crafted expression and work. Can you share when the origin of this collection sparked, how it came together, and when you knew it was ready to seek publication?

Blackburn: The intention was to write a micronovel with the characters in the connected stories from Black Jesus and Other Superheroes. I just kept writing other stories in the middle of that plan, and they all fell into a similar theme. I stopped resisting the flow of stories and kept toggling back and forth until I had a bunch of work that I had to arrange. Even though the intent was to create a novel, I recognized the flash pieces as contained stories. I let them exist in two parts, the first part a kind of panoramic view of a queer girl world from high up and then part two, a kind of zoomed-in look at a single family.

Liguore: What was the most difficult part of writing or gathering stories for How to Wrestle a Girl? What about the most fun—or the part you loved the most, that really synced for you?

Blackburn: The challenge was deviating from my original plan. The writing was always fun because I sat down every day with a kind of idea and a set amount of words I wanted to accomplish, and whatever happened just happened. The ideas were pretty broad, too. I think I had a list of thirty-plus topics like holidays or dick pic, lol, and things just went from there.

Liguore: In the story “Smoothies,” you have an incredible talent to slow time down, to show readers this singular moment, and yet we’re taken through mountains of life and experience—it was like reading through a microscope, super close . . . then a telescope, wide and expansive . . . What, as the author, makes this a compelling way to tell a story?

Blackburn: Yes! That was the plan, and that is my favorite kind of flash fiction, the kind that can go very small and very big, cover whole lifetimes or generations or the range of our entire species. That’s the magic to me. I believe we are intrinsically connected in this reality on a molecular level and another level, call it the soul, call it consciousness, call it pheromones. Whether chemical or spiritual, “Smoothies” is about the blend of us (pun intended) and how we are each other and to condemn someone is to condemn yourself. People project their issues onto me all the time. All the time! We all do it on occasion. I wanted to investigate that with a queer filter.

Liguore: In many ways, for me, How to Wrestle a Girl is like getting on a train and meeting all these wonderfully diverse human beings; it offers readers a journey into the gamut of human expressions they may or may not be familiar with. In what ways is your lived experience informing the writing? In what ways is society today influencing or informing your work? The story “Fat” comes to mind.

Blackburn: Ha, omg, people are my stories; everyone I’ve ever encountered (including all the versions of myself) has given me material. It sounds like I’m using them, but I’m just fascinated and enthralled with us. I can take a guess and say that most girls have had a well-meaning man make unsolicited judgments about their bodies more than once in addition to all the less-than-well-meaning men. That was the genesis of “Fat,” plus setting up the circumstances around the body for the narrator. Their body, the defining of it, is at the quick of the whole second half of the book and circulates through the entire manuscript. I personally have a decent relationship with my body. I love it. It’s cute. I’m mean to it from time to time, but it’s strong and capable. I wanted my characters to have fun in their bodies despite so much meanness in their lives.

Liguore: If you could change places for a day with any one of your characters, who would it be, and why?

Blackburn: Those people are wrecks! I cannot dream of exchanging my life for theirs even though so much of my life is a direct reflection of them. That’s a fun question, though. Gosh, there is a character called Toni in the story “Brim” that is smoking hot, queer, and owns a successful tattoo parlor. She’s cool enough to walk around in for a while.

I’m currently writing some speculative work. There’s a kind of time-traveling dark entity with a great sense of humor in some of my current, unpublished work that I might trade places with. I love agents of chaos because they are so different from how I live my own life with a careful eye on order and less drama.

I love agents of chaos because they are so different from how I live my own life with a careful eye on order and less drama.

Liguore: Are there any tips you can share about writing, things that have helped you? Any advice you can share that really made a difference in your writing development?

Blackburn: Write for yourself first. Write to be understood next.

Liguore: How has the experience of publishing influenced your writing? Do you find yourself considering an audience when you write and so on?

Blackburn: Goodness no. I have a profound fear of disappointment, which is why I eat almost the same breakfast every day or order the same meal at favorite restaurants. That fear doesn’t translate to other people, though. I’m not that worried about disappointing audiences or even close family and friends. That does pop up in my consciousness from time to time and can be paralyzing, so I try not to honor that fear. I want to let the work exist and illuminate the various recesses of our civilization and psyches. After that, I try to make sure my points are clear. Everyone is a potential audience member. I don’t exclude, but I don’t cater to anyone—although I love my queers!

Liguore: What’s next for Venita Blackburn?

Blackburn: Movie deal. JK! There is no movie deal, but talk to me. I’m definitely writing big, overly ambitious books now and letting smaller story ideas simmer, too.

Liguore: One thing you want to leave readers with? Words to live by?

Blackburn: Write like it will save your life.

Ground Fighting (an excerpt)

by Venita Blackburn

Esperanza cursed and ushered me to the seat. I mentioned that I just wanted my fries and no one listened. I didn’t bother mentioning I was grieving a lost parent and just had surgery on my elbow two months ago. If they didn’t care about food, they wouldn’t care about that. My father believed in sports the way he believed in the weather; they guided our days, and we adjusted our whole lives to the games. Without him I lost my faith in balls and sticks.

JV boy’s hand looked relatively clean, but I still didn’t care to touch it let alone hold it tightly for several seconds or more. I looked up at Esperanza. She was nearly taller than everybody even the teachers. I wanted to give her my pocket change and take her places and erase all the other heads even the ladies making the orders in the tiny hot kitchen behind the counter. I wondered if love begins that way, hoping to erase other people’s bodies.

I grabbed JV boy’s palm and held it tight.

Someone counted to three. The pressure engaged. He dug his jagged nails into my skin and shook the table a little. My bare elbow on the wood felt grated and stung. Pain, to me, is a portal, an access point to another world, the smallest of places and those infinite in scale. When I broke my arm, I went to the atoms. When I buried my father, I went to the stars. When I came out to my mother, she told me to wash my hair, then I went to the past. It’s the greatest high when your own body is so wrecked you get to leave it for a while. With his hand in that position he had no chance to win. All I had to do was endure the pinch, the pressure, the sting then pull his arm a little further out and it was over. I won. The screaming was incredible. The boys, the girls, the little ladies in the kitchen giggled like something extraordinary had happened.

“She swoll. She swoll!” The boys chanted.

“Fucking man is what she is,” JV lamented and demanded a rematch.

At that last declaration I felt a different kind of hurt, familiar and wicked. I ignored it and the others ignored it, the suggestion that something about my body was not quite right. But there was a hot and sexy bag of fries on the counter with my number on it. I took them and walked away. The skies in southern California are beautiful in the early evening. The smog ignites in gold and fuchsia. I wasn’t diagnosed as intersex until twelve, more female than male so before that girl was just a good guess. After a few paces I felt I wasn’t alone. Then I wasn’t alone. Esperanza followed me. We said “hey” one after the other.

It was quiet for a while but not a bad kind. She apologized for making me arm-wrestle, but I told her it was fun. She was surprised I wasn’t hurt by what JV said. There was more of that good quiet. I offered her some fries, meaning my heart, my blood, my future. She declined, said she had already eaten.

Editorial note: From How to Wrestle a Girl (FSG Originals, 2021). Reprinted by permission.