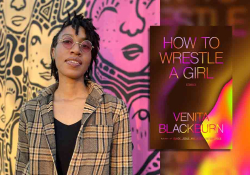

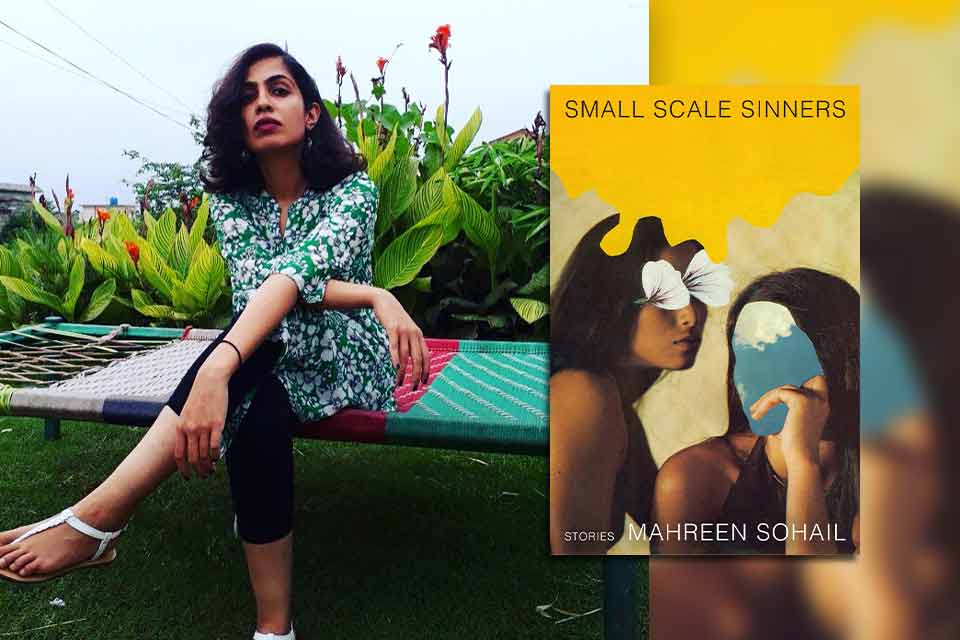

Crafting Stories and Sinful Pleasures: A Conversation with Mahreen Sohail

I met Mahreen Sohail eight years ago when we shared a Tudor-style cottage at Yaddo, the artist residency in Saratoga Springs. When I asked her to send me some of her work, she linked to her short story, “A List of Places My Mother Was Old,” originally published in the Kenyon Review online, and now collected in her fiction debut, Small Scale Sinners (A Public Space, 2025), alongside eleven other excellent short stories. That story turned me into an ardent fan and so perfectly demonstrates her strengths as an artist: it’s short, more a work of flash fiction than a traditional short story, yet resonates deep as a gong. It centers familial relationships. And it is formally playful, elevating the humble list into a work of art. Originally from Islamabad, Pakistan, Sohail has been a Fulbright Fellow and a Charles Pick Fellow at the University of East Anglia. In addition to Small Scale Sinners, she is the author of the craft chapbook, An Expansive Place.

Keija Parssinen: One of the qualities I appreciate most in these stories is the primacy they give to familial bonds. The protective tenderness the children feel for their ailing father in “The Dog” and the beautiful, complicated relationship between sisters in “Sisters” come to mind. The stories seem at once a celebration of blood bonds and an exploration of the complexity inherent to that kind of closeness. How did these stories come to you? Did you set out to write a collection centering the nuclear family?

Mahreen Sohail: I wrote these stories over the course of ten years. I usually just began a story when I thought of an image that interested me and that I couldn’t really get out of my head. I didn’t know there was a unifying theme until I put all the stories together, side by side. It was kind of embarrassing to see my interest in how women function in relationships laid bare in front of me, story after story—but I consoled myself by thinking that maybe everyone’s interested in familial bonds? There were some stories I eventually had to leave out of the collection because they made the book feel repetitive. The act of ordering the collection and choosing which stories went in it was really enjoyable for me.

Parssinen: In the story “Basic Training,” which gives the book its name and is the most overtly political story in the collection, the narrators say, “But children are shaped by the shape of their country” to excuse a cruel decision they make. Throughout these stories, the characters often have an uneasy relationship with an unnamed mother country, taking refuge in its familiarity while dreaming of a life elsewhere. You left Pakistan as a young woman and have built a life in the US. How has Pakistan shaped you? And what did leaving home mean to you as a writer?

Sohail: My parents moved a lot when I was younger, but Pakistan was always home base. It was the only place I could say we returned to for most of my childhood and young adulthood—sometimes for years at a time. And of course, even when you are away from the place you come from, you are still from there. My nuclear family’s unique cultural norms and rules borrowed from Pakistan’s culture and rules. Even though my siblings and I were living away from Pakistan, we were often reminded by our parents about how we were really to prepare for a life living there, rather than wherever we happened to be living at the time. That’s an interesting way to grow up, and it’s telling to me that the characters in my stories have a sense of duty toward home; it hangs over them in good and bad ways.

The characters in my stories have a sense of duty toward home; it hangs over them in good and bad ways.

I moved more permanently to the United States in 2018—in my thirties—so I’ve been living away from Pakistan for longer now (it will be seven years this October). And my writing has changed. I’m more wary of sentimentality because I think now it’s born of nostalgia. I have to think hard about whether what I’m saying is an idea of home or if it is actually about home, and does the distinction really matter in fiction? Moving away has complicated writing for me, and I’m still learning what that means.

Parssinen: While your short stories are wholly original, when I read them, they evoke for me the writing of Jamaica Kincaid; in your treatment of family-of-origin relationships as primal and indelible, in your unadorned yet moving prose, and in your structural play. Can you speak a bit about your influences? Which writers do you love, and how have they shaped your writing?

Sohail: This is a very hard question. Honestly, I’m not a very discerning reader, and I am secretly grateful for that. If a story makes me forget where I am, makes me want to stay up reading, I’m happy with it. I love Jamaica Kincaid, by the way, and Lucy is one of favorite books. I love Toni Morrison’s Sula. Tillie Olsen’s “Tell Me a Riddle” is one of my all-time favorite short stories (it should be required reading), followed closely by Tillie Olsen’s I Stand Here Ironing. I also love Jocelyn Nicole Johnson’s short stories. It’s hard to pick one favorite writer. Lately, I’ve loved Annie Ernaux, how clear yet deceptively complicated her work is. I like things that appear simple but are layered upon closer examination, and I hope some of my writing has that sense of complication as well. Anything I read that moves me shapes my writing. Afterward, I always think, I would like to make someone feel that way too.

I like things that appear simple but are layered upon closer examination.

Parssinen: When we first met, you taught me the expression “scented literature,” a category of writing that exoticizes the otherness of its locale for a white, Western audience. These stories are “placed” and have a distinct setting and cultural context, but they never mention Pakistan by name and don't lean heavily into the kind of set-making we often see writers engage in when writing in English about the Global South. Can you talk about how you view place and setting as craft elements in your work?

Sohail: I will confess, I didn’t name Pakistan in any of the stories because anytime I did, I felt like the story immediately became claustrophobic. I suddenly started putting all this weight on the work that wasn’t there before, and removing the name gave me license to be more playful. I think this is a me problem, though, and there are many excellent writers who can call a thing by its name and be imaginative and playful and do amazing things with it. For me, Pakistan evoked a particular set of emotions, and sometimes I didn’t want the story I was working on to be associated with those particular emotions—I wanted the piece to do its own thing. Still, I wanted the undercurrent of place to run through the stories. So, I added signifiers carefully, sometimes during the revision process, or sometimes I removed them when they felt too heavy or on the nose.

Parssinen: Several stories in the collection play with a kind of list format: “Sisters,” “How to Raise American Children,” and my all-time favorite of your stories, “A List of Places My Mother Was Old.” What attracts you to the list as a mode of formal play?

Sohail: Lists are wonderful! From no. 1 to 2 you can leap through decades, places, people, etc. They allow you to be more flexible than regular old prose, and they secretly make me feel like I am a poet, so I enjoy doing them. It also feels less like writing, you know? You can dispense with then this happened then that happened and get straight to the point.

Lists secretly make me feel like I am a poet, so I enjoy doing them.

Parssinen: The jacket copy for the collection states that these stories are concerned with the question, What does it mean to be good? So often for writers, thematic concerns emerge unconsciously. How do you approach theme and meaning-making in your work?

Sohail: Yes, I agree that thematic concerns emerge unconsciously. I’m not sure I think much about what a story is trying to say until after I have written it. But once I’m done, I put it away for a while and go back to the piece and try to look for its center—what makes the story tick often becomes clear after some time away from it—and sentences and paragraphs that work also start to stand out. I then do edits based on that information. I try and move things closer to what the story is about, still not necessarily thinking about themes, but more like, Oh, so this character is worried about that, maybe I should press into that a little bit harder. That helps clarify things for me, and that’s good because short stories are distilled by nature.