Searching for Mohamed Choukri, the White Sparrow of Tangier: A Conversation with Jonas Elbousty

Mohamed Choukri (1935–2003) is considered among the most ambiguous twentieth-century authors in the Arab world due to his bold depictions of Tangier’s underbelly and its world of the marginalized and destitute. He paved a path of his own in the world of literature, relying both on the harshness of his personal experiences and on his interactions with life, literature, and the most cultured minds of his generation that visited Tangier during its richest moments. Nevertheless, there remained a distance between him and the majority of intellectuals and critics due to his honesty and directness in discussing himself, his experiences, and the events and people that occupied his environment. Al-Khubz al-Hāfī (translated as For Bread Alone), his first work (and the first of a trilogy), has been translated into thirty-nine languages, whereas the rest of his corpus has not attained a similar prominence, overshadowed by the boldness of his debut book.

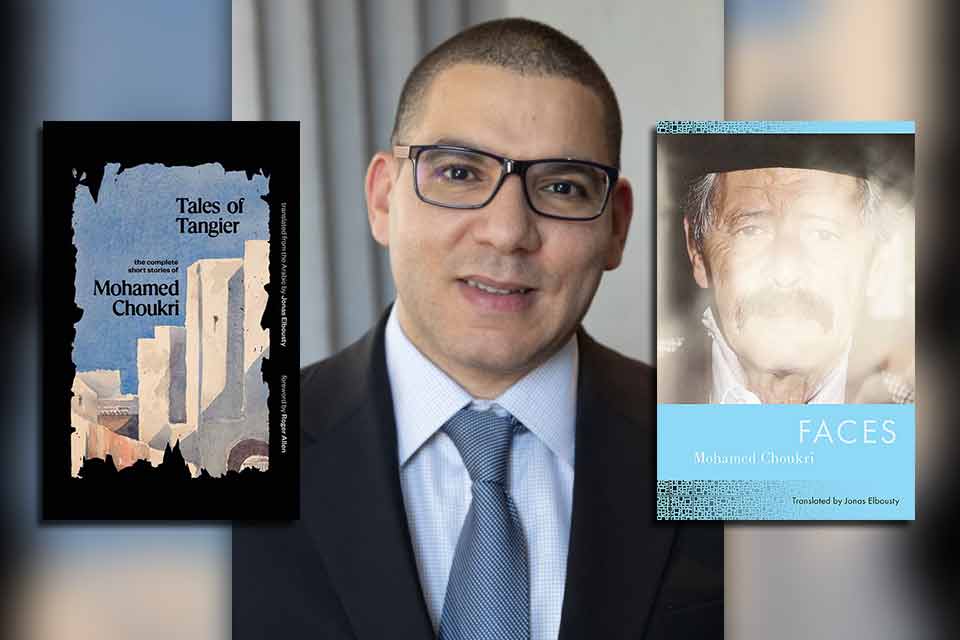

Moroccan American professor Jonas Elbousty has dedicated himself to fixing this discrepancy, translating a collection of short stories under the name Tales of Tangier (Yale University Press, 2023). Moreover, he recently translated the final book in Choukri’s trilogy, Faces (Georgetown University Press, 2024). Alongside Dr. Elbousty’s academic and administrative positions at Yale are his roles as translator and literary critic, procuring various awards such as the Ordre des Palmes Académiques (Commander of the French National Order of Merit), the 2020 Poorvu Family Award for excellence in teaching at Yale University, a special commendation for contributions to education from the Massachusetts State Senate, as well as many research fellowships, among them from the American Institute for Maghrib Studies (AIMS).

Seeing the lack of translations into English of Arabic literature, he has taken up the mission of introducing American academia to the works of illustrious Arab authors through translations, lectures, and courses. His current project revolves around additional translations of Choukri as well as works by authors whom he dubs “the pillars of Moroccan literature.” In addition, he has many poetic translations of contemporary Arab poets. We had two conversations with him (one after the release of Tales of Tangier, the other after Faces) on why we must reread Mohamed Choukri today.

Suzan Almahmoud: Why did you choose Mohamed Choukri over many Moroccan authors? Does postcolonial literature inform that choice, or is it a personal project?

Jonas Elbousty: Yes, it’s a personal project, a long-standing passion that is simultaneously personal and academic. Choukri is an exceptional character situated in a specific historical moment. Amazighi (Rifian), he migrated to Tangier with his family from the mountain ranges of the Rif, escaping famine, under the illusion that Tangier could offer bread, as his mother said in his autobiography (and what my book with Dr. Roger Allen, Reading Mohamed Choukri’s Narratives: Hunger in Eden, refers to). But Tangier was a lamentable city under international custody (Spain, United Kingdom, France, United States, etc.). As a result of colonization, Choukri and a vast portion of Morocco’s population experienced poverty, despondence, homelessness, violence, illiteracy, and imprisonment. He worked the most menial jobs to sustain himself until he began his education at the age of twenty, bursting forth into the literary world.

I first heard of Choukri when I was thirteen. His works, especially al-Khubz al-Hāfī, were banned in Morocco, but he was a beloved figure among the people. I found a copy of this book in our own library when I was fourteen. I was astonished, and my intrigue only grew when I dived into his autobiography. Rather early on, I chose to dedicate myself to his literature and to study his works. At a time when my peers were focused on studying Western authors, I was focused on introducing Choukri to universities across the United States and the rest of the world. Fifteen years on, I continue to work on him both through research and translation.

Almahmoud: You told me that you organized a conference on Choukri at Yale. Could you please tell us more about it?

Elbousty: I organized the first conference in English on Choukri at Yale University in October 2022. I also taught the first class on him to university students in the United States, where we read the majority of his works in both undergraduate and graduate settings. Namely, his trilogy (For Bread Alone, Streetwise, Faces), the collections of short narratives (Flower Crazy, The Tent), and everything Choukri wrote as memoirs (Paul Bowles: The Recluse of Tangier, Jean Genet in Tangier, Tennessee Williams in Tangier). I also gave lectures on him in many countries such as China, Sweden, Australia, Romania, and Belgium. Aside from Choukri, I have also taught Ahlam Mosteghanemi’s trilogy.

Most people know For Bread Alone but are unaware of the rest of his work, so much so that Choukri would say, “For Bread Alone is my curse.”* Though he has published a number of important books, he is still only known as the author of al-Khubz al-Hāfī despite the multitude of achievements throughout his life. Choukri had verbally dictated the novel to his friend Paul Bowles, who would record it, then proceed to rewrite it. It was published at first in 1973, in English, and its orientalist tinge was quite apparent. Then Tahar Ben Jelloun translated it into French in 1980. It took until the year 1982 for the book to be published in Arabic in Morocco, having been personally financed by Choukri. In 2021 the renowned author Mohamed Berrada wrote a message directed at his dear friend Choukri in memoriam (Choukri had passed away in 2003). I translated the letter to English, and it was published in World Literature Today, an illustrious American publication almost a century old.

Almahmoud: We are all aware of the dangers of translation and the responsibility a translator bears in transporting a work from one native language and culture to another. Did you face any difficulties in translating Choukri’s worlds and the richness of their local spirit?

Elbousty: Yes, there is a certain difficulty. Translation to me is associated with the idea of savoring and reading. I read a text multiple times until I feel it and comprehend it entirely. Often, I spend a long time savoring it, taking it in, after which I create several drafts, then I choose the best one. I am often trying to transmit the spirit and atmosphere of the text to the English reader.

Almahmoud: What is the significance behind Tales of Tangier today, especially as a work published by an eminent press such as Yale University Press and considered among the best translations of this year? Your last book, Aswat Mu’asira, was published by Georgetown University Press. Is this an official declaration of interest in Arabic literature from the American academic community?

Elbousty: In all honesty, to this day American academia’s interest in Arabic literature is quite limited. Perhaps one of the reasons that drove me to delve into translation in this project is the severe lack of translated Arabic literature into English. When I was a student, studying world literature, there was not a single Arabic author mentioned in the syllabus. That was for many reasons, among them the rarity of publishing houses that translate Arabic literature into other languages and the rarity of prizes in Arabic literature (though the Booker has improved the situation slightly, it remains insufficient).

This is why I translate from Arabic to English, because the collection of stories compiled in this book are of great importance. I compiled the stories of two collections by Choukri: Flower Crazy and The Tent, which account for most of his short fiction, because I wanted to introduce them to readers. The approval of Yale University Press with regard to the book was vital. Since its publication we have amassed a great number of academic readings for the Tales of Tangier, and my translation of these stories has been categorized as among the best in World Literature Today. My translation of Choukri’s final volume in his trilogy, Faces, means that the Western reader will have access to the entire trilogy for the first time. The translation of our poets and authors into English is a matter of great importance. It allows our literature to possess its own space within world literature, and translation is a fundamental pathway to achieving this.

Almahmoud: To what degree do you believe that reading the literature of a certain country helps rectify the global perspective toward it?

Elbousty: Culture is very complex and its effects are vast, wide, and often indirect. In my opinion, I believe in the aesthetic value of literature affecting us and the change it inspires in the reader after finishing a text. I consider the translation of a good literary text to be both an intellectual and aesthetic endeavor. The translator creates a new text in an attempt to channel the original, thus participating in the creation of literature.

I believe in the aesthetic value of literature affecting us and the change it inspires in the reader after finishing a text.

Almahmoud: Thanks to technological development, instant translation has become viable and accessible to all. How do you envision its role? Does this pose a threat to the work of the translator and researcher? Are their responsibilities different today?

Elbousty: Translation software is incapable of taking the place of the literary translator. One cannot translate poetry or prose using software. The literary translator is versed in literature and savors it. When she produces a poetic or prosaic translation, she exerts a great effort to create a new text that will forge its own path in a new language. The translator too is an author, a creative mind. In the past, publications would not name translators for marketing purposes. Today we find both the name of the author and the translator on the very first page.

Almahmoud: Professor Roger Allen writes in his preface to the book about the depth of Choukri’s excellence in terms of memory, as well as the traits that set him beside such greats as Poe, Gogol, Maupassant, Zakaria Tamer, and Yusuf Idris. Namely, he spoke of his narratorial instincts and of capturing the secrets of a location as diverse as Tangier. What is your comment on this?

Elbousty: Choukri differs completely from the others, but we won’t mention his life of extreme difficulty because Zakaria Tamer, too, had a difficult life. One of the fundamental differences between Choukri and the rest is that Choukri created and wrote through memory alone. Since he remained illiterate for a long time, a period that extended two entire decades in the alleyways of Tangier, there was a very active choice on his part in terms of what to include in his autobiography. In relation to Choukri, most authors would not dare to write such things. Oftentimes, autobiographies speak of great achievements by a person, yet when we read al-Khubz al-Hāfī, we find the intense suffering and difficulties that his childhood, adolescence, and adulthood were steeped in. There is no glory, victory, or achievement; in fact, the opposite is true: a bitter and wretched reality among the city’s populace.

He is without literary forefathers. His true mentors are life and his experiences on the streets. He is equipped with a style of simple language and smooth expression. It is the simplicity of literature that tastefully conveys the depth and effect of his images. Choukri is completely resistant to sugarcoating the ugliness of the world. He tells things as they are, yet he still narrates in a charming and beautiful way, thereby raising the lowly world up to the heights of mankind’s refined literature.

Choukri is without literary forefathers.

Almahmoud: Can we speak about your new book, Faces, which commemorates twenty-one years since the passing of Choukri? This book is the third in his autobiographical trilogy and has received quite a warm academic reception. As Robyn Creswell from Yale University put it, “In this surprising finale to his fictional-spiritual autobiography, Choukri cedes center stage to a vivid cast of characters—confreres, rivals, alter egos. And yet he is the man and writer we have always known: penniless and cursed, empathetic and profane, our best guide to the nights of Tangier.” What are the difficulties you faced in this book?

Elbousty: Yes, I translated Faces, and I am the first to render it into English, making the trilogy (For Bread Alone, Streetwise, Faces) available to the English reader. It’s quite important, and the book talks of the various faces Choukri encountered and befriended in Tangier, local personalities with their own personal identities. The book also reflects on various locations and how people relate to place, and traces the changes that the city and its people underwent.

* * *

The following is a continuation of our conversation with Professor Elbousty in November 2024, after the publication of Faces.

Mohamed Choukri says, “Whoever invented the mirror is not necessarily a narcissist. Perhaps he invented it to distinguish himself from those who evade seeing their own faces in it. If mirrors surround you, where would you hide your face? That is if the mirror did not invent itself.”*

On November 15, 2024, the twenty-first anniversary of the passing away of Mohamed Choukri, Georgetown University Press published Choukri’s book Faces, translated by Moroccan-American Professor Jonas Elbousty. This book is the final volume in Choukri’s autobiographical trilogy. For Bread Alone was published first in English in 1973, translated by Paul Bowles, then in Arabic in 1982. The second volume, Streetwise, originally came out in 1992, and then was translated by Ed Emery. Faces came out in Arabic in 2000. Now Jonas Elbousty has translated Faces, making Choukri’s entire trilogy accessible in English. The significance of this publication of Faces is that it marks the first English translation of Choukri’s book. The book showcases Choukri’s exceptional talent and portrays him with greater maturity and awareness among the people of his city, Tangier, throughout his intellectual and personal experiences. This book was completed three years prior to Choukri’s passing, providing an image of the quintessential Choukri (in all manners quotidian, social, and intellectual).

Tangier was a favored spot of the authors, thinkers, and artists of the world when it was an international zone. These transformations are seen throughout the stories in this collection, and the character development of certain characters (such as Fati in “Love and Curses” and “She Comes Back,” among other Tangierian faces) belongs to Tangier as a whole. Nevertheless, Choukri sketches his characters with a creative depth, such as Hamadi the gambler, or Moncef in “News About Death and the Deceased,” Ricardo who is possessed by a love for Tangier, Baba Daddy, and others. We speak here with Professor Elbousty, a specialist in the works of Choukri (whom many call “the wretched author”), and of whom Mohamed Berrada said: “Mohamed Choukri was educated in the language of coarseness and nudity much before learning expression through words.”* Hence, his daily life is his essence. Writing, to him, comprises a partial addiction, and he refuses to turn it into a beautifying mask or a medium of social climbing.

Almahmoud: Professor Elbousty, why are we in need of rereading Mohamed Choukri today, both through an Arab and Western lens?

Elbousty: Because we have a serious problem, a massive injustice against Choukri’s literature that the Arab world has yet to rectify. His books were banned from the syllabi of Arabic universities, and it is impossible to forget what happened at the American University of Cairo in 1999, when Professor Samia Mehrez attempted to teach al-Khubz al-Hāfī, only to be stopped and the book to be banned. It made quite a noise back then. It has always been the case that Choukri was subject to a preconceived judgment, before he could speak or write a word, as a result of how he grew up. He spoke the language of the Rif, then learned the Moroccan dialect, and then learned to read and write in Modern Standard Arabic. He suffered unwarranted prejudice for the majority of his life. His literature was denigrated because of conservative views on al-Khubz al-Hāfī, and he was punished for shining a light on what was taboo. Yet, in spite of all this, he wrote with unprecedented daring in stories like “Violence by the Shore,” which Suhayl Idris liked and published in the Lebanese publication Al-Adab in 1966. That is also where his 1979 collection Flower Crazy was published, but the publishing house feared publishing For Bread Alone.

Almahmoud: In the beginning of Faces, Choukri talks about his city and its market with great sorrow in the chapter “Love and Curses”: “We’ve all gotten older, but life here is rotten and doesn’t age gracefully. Even memory grumbles and complains, refusing to record any part of what is left. The skin of those who work permanently in the souk has not only shrunk and shriveled; it is also decomposing and covered with pustules. The fantasy of regaining their ancient glory is eating them up, turning them pale, and making them resent the changes that have defeated them in this blighted city—this corpse that hasn’t yet been buried. The disease has reached the heart, a stroke from which the city may never recover. Its veins are torn out every single day, and it’s going to explode!”

Elbousty: Choukri was a very reflective man and was unabashedly honest in relaying the emotions of his characters. He knew the environment he grew up in more than anyone else. He never produced literature to appease or please others, but to reflect on a city and its people. I translate Choukri out of both love and responsibility. I agree with Roman Jakobson when he says, “Translation is the interpretation of a text’s meaning. It is impossible to produce total equivalence between two texts because languages are themselves naturally untranslatable.”* This is why I focus on translating the spirit of a text and its atmosphere.

I focus on translating the spirit of a text and its atmosphere.

And we know that Choukri’s relationship to Tangier is quite problematic, as he speaks of the city’s own suffering and the effects of colonialism on its population. We find this clearly in al-Khubz al-Hāfī where he speaks of prostitution, poverty, social divides, and the disidentification of society. Though one may say that Morocco’s status as a protectorate (1912–56) did not persist nearly as much as Algeria’s, the effect on Moroccan society was still large and devastating. There is room there to discuss a myriad of problems created by colonialism.

Almahmoud: Choukri, on several occasions, has defended his artistic portrayal of women, as he was accused by some to confine the women in his narratives to a single archetype: the prostitute. And though Choukri does portray women as the victims of patriarchal and masculine oppression, as well as poverty and social excommunication, he also utilizes the various changes and experiences in their lives to map out the society of Tangier from its time as an international zone up to its independence. Moreover, in Faces, he writes that the emergence of a “regular” Moroccan woman was very rare at that time. We can understand from his words that the Moroccan woman (particularly from Tangier) at that time could not participate in a normal life. Therefore, Choukri focuses on the archetype of the prostitute found in bars, but within a humanizing context, because she is the only archetype to be found in day-to-day life next to a man. What are your thoughts on this?

Elbousty: A person must read the majority of Choukri’s work to understand his perspective on things, to understand his position as an author that undresses society, disentangles its patterns, and speaks truthfully of all things about which silence is demanded. Bars came about in Tangier as a result of colonialism, namely Spanish colonialism, when bars opened as a means of entertainment for its soldiers. There was a period of time with vast numbers of foreign women (and some Moroccan women too) in these bars, and the proof is that many of these were shut down after the end of the colonial protectorate. Choukri showcases how women were among the many victims of colonization in addition to their struggles against traditional patriarchy.

This is most widely portrayed in For Bread Alone, which drove many critics and intellectuals to denigrate his literature and to consider it as immoral eroticism. However, there is no truth to this label because Choukri, throughout his works, showcases how women are pushed into these wretched circumstances (poverty, domestic violence, social issues, political repression) by society, the primary perpetrator. Many developed a shallow, preconceived notion since the publication of For Bread Alone and did not wish to reconsider it.

Almahmoud: Choukri references a quote at the beginning of “Love and Curses” in Faces: “Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn’t ask ourselves what it says but what it means, a precept that the commentators of the holy books had very clearly in mind.”—Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose. Is Choukri here responding to his critics and their ethical judgments of him? To what degree was it possible to translate this pain into another language?

Elbousty: Yes, Choukri invites us to reflect here and informs us in advance that simplistic and blind judgment is incorrect, especially with regard to rereading his literature intelligently. To read between the lines, this may be the only quote Choukri produced in Faces because he wished to respond through Umberto Eco to the accusations against him. He wishes to speak to us of the relationship between the reader, the text, and the significance of interpretation in the reading process—the literality of text. Through interpretation, Choukri was acquainted with various theories of literature. He read philosophers and thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, Jacques Derrida, and namely Roland Barthes, who wrote on the death of the author and how the text responds to the reader’s interpretation distantly from the author, saying once that “the birth of the reader must be on account of the author’s death.”* (La naissance du lecteur doit se payer de la mort de l’auteur).

Almahmoud: Some characters in Faces, though inspired from the author’s life, seem to evoke over time certain impressions of the “fantastic.” Not being carried away by dramatic extremes, he only showcases a fraction on the surface while the roots strike into the depths of Moroccan and Tangierian society. In particular, the character of Moncef in “News About Death and the Deceased,” Farid in “The Death of a Hippie Fish,” or others such as the brothers Ahmed and Khalil in “Solitude.” Are there critical studies dedicated to this?

Elbousty: No, unfortunately. There are very few critical studies, most of which (though still insufficient) are on For Bread Alone. In terms of creating a literary character, we find in Choukri a true mixture of reality with fantasy. There are real characters, and we know that many of Tangier’s storytellers know this. Choukri differs from others (such as García Márquez) in that his work does not belong to magical realism. He creates characters and produces quotidian narratives, yet he imbues them with a fantastical element. He sets off from the depth of human experience, aided by his personal memories.

For example, Moncef, one of the many known characters of Tangier, is obsessed with news surrounding death, yet he is still a face from Tangier subject to social marginalization. There are many faces of marginalization there: social, economic, and intellectual—sexual, too, when it comes to isolating women from their roles and ascribing them to male authority. Choukri is much like the French author Émile Zola or Maxim Gorky, the literary and intellectual thinker who played a role in moving Russian literature forward through real depictions of society. Much like Gorky was concerned with the rights of the impoverished, Choukri too wrote about the impoverished class, marginalization, prostitution, without pointing to a specific person, yet still conveying his message to the reader. Choukri is distinguished by his reflections on timeless themes we find everywhere and anytime such as marginalization, prostitution, corruption, despotism, and colonialism, all being the various traces behind him.

Choukri is much like the French author Émile Zola or Maxim Gorky, who played a role in moving Russian literature forward through real depictions of society.

Almahmoud: Choukri says “the revolutionary carries his youth with him to battle, both in thought and in action. A young romantic remains a witness to the age of martyrdom, in which he only participates as a bystander. The revolutionary does not wait for inspiration.” To what degree is Choukri’s literature considered revolutionary?

Elbousty: He was certainly a revolutionary in all that he presented in his literature. Particularly in terms of disentangling society’s diseases and diagnosing its issues, he speaks on the influence of authority and colonialism on individuals. When he was imprisoned for a brief period, he first heard the verse of Abu al-Qasim Chabbi “If the people one day wished to live,” which stands among the myriad of things that motivated him to read, write, and describe things as ugly and terrible as they are. He became acquainted with littérature engagée through reading Sartre and others, developing a critical sensibility. Moreover, he partook in creative writing that went against the prevailing sentiments in Moroccan and Arabic literature at the time.

Almahmoud: Can we talk about the poetic side of Choukri, one of the more mysterious aspects of his personality? We find its traces in the beginning of some stories in Faces as well as in The Temptation of the White Sparrow.

Elbousty: In reality, Choukri wrote several poems, some of which we can find in Streetwise. Among them is a very important poem regarding his passion for Tangier and his problematic relationship to it, titled “Tangier.” Unfortunately, Ed Emery did not include it in his English translation. It begins:

They talk of you, that your mud brings salvation

That Noah sought refuge in you

That he is a pigeon, a hoopoe

a crow.

Between two waves,

Tangier begat the froth of sailors.

Upon your virginity followed

scalpels of lust and conquest

hermitage of liberation and transmigration.

Bacchanalia

unleashed frenzy in loins

and delirium in the ocean bleats

As if the horse lamented Troy,

As if she were a dying bride

kindled by Zeus

He mentions in Streetwise many Spanish poets introduced to him by Moroccan author Mohamed al-Sabbagh. He also read many American poets that were translated into Spanish, French, and Arabic. He was passionate about reading poetry, but the majority of his writing was in prose.

Choukri has a particular view on translation, which we can find in his book The Temptation of the White Sparrow: “The tribulation of the Arabic author today is that he is demanded to develop his technique and subject-matter more than he ever has been demanded to. He is a competitor to the Western author both in origins and in translation, which has exceeded the stage of quotation, derivation, and Arabization.”

Almahmoud: He writes in a footnote about Youssef El-Hajj, critiquing him in his book In Defense of the Arabic Language, that translation is a “means, not a necessity,” and that “what matters to the author is not correct expression, but beautiful expression.” It seems to me that he exaggerated the nationalism of language, otherwise what would he say about authors who excelled in foreign languages such as Gibran Khalil Gibran, Samuel Beckett, or Eugene Ionesco? We do not write to seek the beauty of a pure expression, but to find the final truth in life. The connection between us and ancient civilizations is more intellectual than linguistic. Homer died linguistically, and al-Ma’arri is dying, yet they live intellectually. What are your thoughts on this as a translator?

Elbousty: Yes, he is saying that we may overcome language; I believe he is implying that the idea or the intellectual element, as a thing itself, does not have strong ties to language. Ideas transgress time and are entirely universal. An idea may be set free from the shackles of language, and it will continue living. This proves the intelligence of the man and the sharpness of his critical thinking. We see how the author of al-Khubz al-Hāfī tackles these major ideas. We can feel the extent of his intellectual development over the years because of his prolific reading and knowledge of many languages such as French and Spanish.

An idea may be set free from the shackles of language, and it will continue living.

Almahmoud: Very early on in The Temptation of the White Sparrow, Choukri evokes the case of translating Arabic into other languages, a rather thorny topic, which he has suffered from alongside many great Arab minds. He mentions the inequality of translation between the Western languages, namely English and French. These are languages whose excellent, translated works had a serious effect on thinkers in the Arab world, whereas the translation of Arabic into other languages remained very rare, save for limited occasions at the hands of orientalists. This deeply affected the prominence of Arabic literature in the scene of world literature. What are your comments on this?

Elbousty: In agreement with him, I say the current discrepancy is a result of Eurocentrism and Western cultural hegemony. There is an authority given to European languages like Spanish, French, English, and German. Nevertheless, the essential problem at hand is the rarity of translating Arabic into other languages. Many translators and Arab thinkers neither believe in the beauty of the Arabic language nor the significance of its prose, which culminated in a large gap of intellectual exchange between the Arab and the Western world over many decades.

Almahmoud: Choukri writes in The Temptation of the White Sparrow, “Our literature resembles Black literature, whose only concern is their cause in relation to the white race. Our real duality is in the fact that we critique the licentious expressions of the West, demanding a return to our values of chastity and modesty. However, we (both secretly and publicly) import the latest financial and intellectual expressions from them.” He says of Arabic literature that “it is much more a literature of recording and appeasing than a literature of thinking and changing. We do not demand the abolition of regional literature, but we demand its evolution beyond mere national traditions, such that we make universal myths out of regular people as Tayeb Salih did in Bandarshah or Gabriel García Márquez in most of his works or Juan Rulfo in his stories.”

To what degree was Choukri’s interaction with criticism, critical reading, literary theory, important to his work?

Elbousty: We can clearly witness the beginnings of his passion for prolific reading in Streetwise, through literature and criticism. He read the majority of what renowned Western thinkers and theorists were writing at the time, in addition to his friendships with those who passed through Tangier and the renowned Moroccan authors of his time such as Mohamed Zafzaf, Mohamed Berrada, Ahmed Abd al-Salam Baqali, and others. Yet in the end he returned to his living, personal experiences after honing them through reading.

Almahmoud: Can you tell us a little about Choukri’s relationship with Tangier?

Elbousty: In Faces, we see the problematic relationship between Choukri and his city of Tangier. He accompanies his city, creatively observing its transformations through narrative. He dives deeply, observing everything from its lowliest inhabitants to its intellectual elite. He was also an expert in its past as an international zone under Spanish and French colonialism. He mentions that Tangier’s international fame coincides with its beginning as a protectorate (March 30, 1912) and the 1928 International Zone Statute amending the Paris Convention (December 18, 1923) to turn it into an international zone. He writes on the freedom encouraged by the lack of laws criminalizing unfamiliar moral and sexual acts, which had played a major part in its former tourism, and which rendered it a site of pilgrimage for thinkers and intellectuals of the Western world. It acted (until its independence) as a hub for many Europeans escaping civil wars and pursuits, such as in Spain since it connects Africa and Europe.

The effect and residue of colonization was palpable: its society had recoiled into conservatism and religiosity, as though liberality and freedom were a distant past guided by temporary politics. We can follow that in Choukri’s works. He talks, for example, about the stories behind paintings on the walls of bars such as the portrait of Hemingway. He depicts people as being affected by famous visitors of Tangier, though in a shallow, limited, and perhaps touristic manner, whereas Tangier leaves a deep impression on those who visited it or resided in it. Hence, the spirit around Tangier and its large bars denotes it as a cosmopolitan city, or as Choukri says in Faces, “Her legend is stronger than her history.” He portrays the number of intellectuals, artists, and authors who had visited Tangier but did not merit a portrait on the walls of its bars as being forgotten. They invent stories about people who never stepped foot in Tangier yet whose wall portraits allow them to believe that they had been in Tangier.

Choukri accompanies his city, creatively observing Tangier’s transformations through narrative.

Almahmoud: Choukri suffered many ethical judgments from Arab critics as a result of his daring exposition and dissection of his life and his city’s life. How does the Western world receive his literature today?

Elbousty: Yes, and Choukri was not the only one to undergo this. Many important thinkers and authors faced ethical and legal accusations such as Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, and others. Any person who pushes against the grain is faced with these circumstances, but time reconsiders these creative minds. We hope that time is capable of redefining the persona and work of Mohamed Choukri, whose literature deserves rereading and appreciation in the Arab world. As for the West, Choukri’s books have been translated into many languages, and we are currently trying to translate most of his literature into English. I am personally trying to evaluate and introduce him in the context of American universities, where his work has begun to gather significant interest.

Almahmoud: Choukri’s friendships with the various important authors who visited Tangier have been well known. There are a few books on this topic: Jean Genet in Tangier, Tennessee Williams in Tangier, and Paul Bowles: The Recluse of Tangier. Can you tell us more about this work?

Elbousty: Yes, Choukri met Paul Bowles through Édouard Roditi in order to translate For Bread Alone (al-Khubz al-Ḥāfī), which had been called Min Ajl al-Khubz Waḥdah. Choukri would dictate the book in Spanish, and Paul Bowles would turn it into English. However, their relationship faced many issues because of Choukri’s constant questions, the nature of Bowles (who would prefer illiterate Moroccans), and because Bowles used Choukri by not granting him rights to his book For Bread Alone. As for Genet, their relationship was good. Choukri accompanied Genet for the majority of his stay in Tangier, trying to benefit as much as possible from their literary discussions. He was also friends with Tennessee Williams, but he was much closer to Genet.

Almahmoud: Professor Elbousty, you have taken up the important burden of introducing Choukri to Western universities and audiences by translating his works into English. What have you achieved thus far as a translator and researcher, and what are your future projects?

Elbousty: I have translated many of his books: Tales of Tangier (Yale University Press, 2023), for which I translated Flower Crazy and The Tent; Faces (Georgetown University Press, 2024); with others forthcoming. I also co-edited a volume entitled Reading Mohamed Choukri’s Narratives (Routledge, 2024).

In terms of research, I currently have two book projects on Mohamed Choukri. The first is a biography of his life, literature, and works. I am conducting extensive research, reading, and referencing much of what has been written about Choukri in Arabic, Spanish, French, and English despite the scant literature on him in English. The other book will be titled Moroccan Literature as World Literature: Mohamed Choukri as an Example.

Almahmoud: In the end, Professor Mohamed Berrada speaks of Choukri in the introduction to Flower Crazy: “The young Mohamed Choukri advances all alone to begin a life of vagrancy without knowing what school is. He begins exploring the city and life through various manual labors: shoeshining, vending groceries and newspapers, working in cafés and restaurants, joining a pickpocketing gang, guiding tourists, mimicking songs by Mohamed Abdel-Wahab in cafés. . . . He now approaches nineteen years of age and he has tried everything. He has taken in the nature of relationships and interactions, he has known cruelty and never knew compassion. His intelligence urges him to march onto a path that allows him into the world of those who speak a language unlike Rifian or Darija, until no scene is foreign to him and no youth associate him and ridicule him with his illiteracy. At this advanced age he travels to Larache looking for an elementary school to accept him. There he learns from younger students much more than he does from teachers and instructors. He returns to Tangier ‘educated’ to begin a new, exciting adventure with writing and literature. However, the Choukri that was penetrated by the rot of life and the temptation of experience does not withdraw into his cocoon. He seeks life through addiction to the cup of the night, fleeing ignorance and stupidity, fleeing insanity and death.”

Elbousty: He was unprecedented in stripping down society and displaying truth as it is. He daringly approached topics that people would shy away from mentioning—topics that Arab readers tolerate from Western authors, but never from an Amazighi, Moroccan author. His painful experiences and personal philosophy were the only riches he used in facing the world.

Translation from the Arabic

Author’s note: All quotes or poems followed by an asterisk (*) were translated by Mustafa Zewar and were not supplied from another translation.

Jonas Elbousty holds an MPhil and a PhD from Columbia University. He is an academic, writer, and literary critic and translator. He teaches in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at Yale University. He is the author or co-author of nine books, including Faces (2024), Reading Mohamed Choukri’s Narratives (2024), The Screams of War (2024), Tales of Tangier (2023), Aswat Mu’asira: Short Stories (2023), and Vitality and Dynamism: Interstitial Dialogues of Language, Politics, and Religion in Morocco’s Literary Tradition (2014). His forthcoming books are Zoco Chico (Georgetown University Press) and Exploring Contemporary Arabic Novels (Routledge).