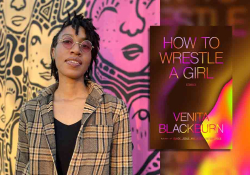

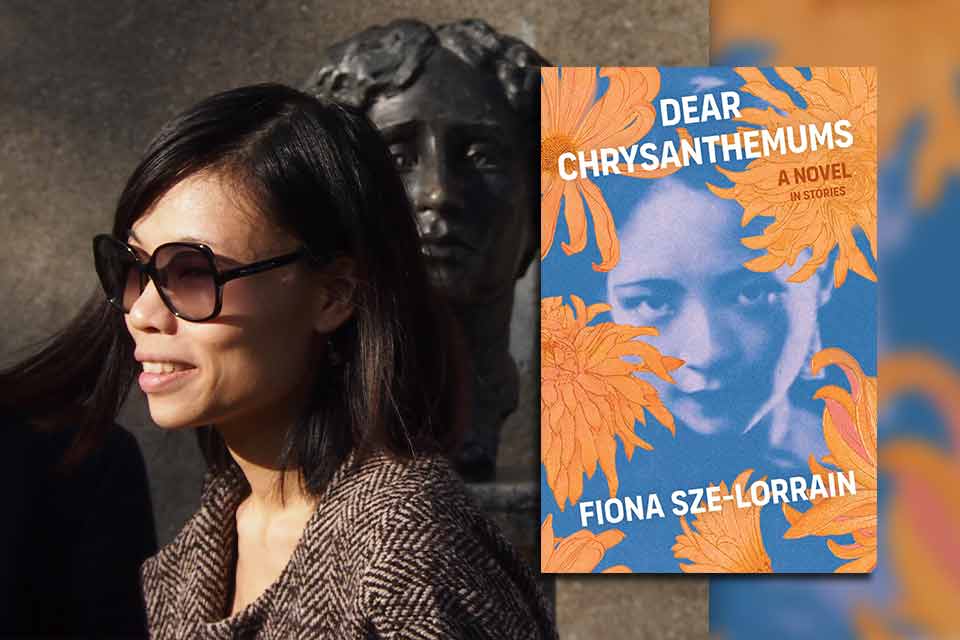

The Infinity of a Heart’s Expanse: A Conversation with Fiona Sze-Lorrain

At the heart of my conversation with Singapore-born, US-educated, Paris-based writer, translator, musician, and artist Fiona Sze-Lorrain are two of her latest publications. Her novel in stories, Dear Chrysanthemums (Scribner, 2023), and her rendering of Mirror (Zephyr, 2025), by Chinese poet Zhang Zao (1962–2010), though distinct, both question the simplistic ideas of what it means to be Asian in a global context and meditate on this identity through art and exile.

Sze-Lorrain takes apart the notion of a fixed blueprint and sheds light on how her fiction instinctively mirrors her lived experience as a citizen of the world. On the diasporic Chinese women characters from Dear Chrysanthemums, she notes: “Their narratives could mirror a subjective historical memory, more specifically the fragmented nature of diasporic identity.” She also speaks of writing’s corporeal aspect, evocative of the dexterity of a musician and calligrapher.

In this interview, Sze-Lorrain shares about her translation practice not as a linguistic obligation but as an act of charting anew one imagination onto another. It is, for her, a rummaging for the refined quality of silence within a text’s very own architecture.

Alton Melvar M. Dapanas: In your novel in stories, Dear Chrysanthemums, you trace the lives of Asian women across eras, from the Cultural Revolution to modern-day diaspora in Shanghai, Nanjing, Paris, New York, and elsewhere, mirroring your own life between cultures. The book’s architecture as interconnected stories rather than a linear novel feels essential to the project. Could you speak to how this form serves the content?

Fiona Sze-Lorrain: The form came last. This isn’t always the case, but for Dear Chrysanthemums, I wasn’t writing with the concept of “interconnected stories” in mind. When most chapters were done, I began to realize that their narratives could mirror a subjective historical memory, more specifically the fragmented nature of diasporic identity for my woman characters.

Instead of patching up these fractures, erasing or making them invisible, I decided to thread the stories not just through the protagonists but also places, time, coincidences. I experimented with different ways in their stories. I used numerology. Each story begins in a year that ends with six, a number that signifies in Chinese divination a “smooth life.” It’s an irony, of course, as none of the women has led a peaceful life.

Dapanas: Speaking of the shattered form mirroring a splintered identity, it unveils the turmoil in the characters themselves amid the trauma and wartime upheavals. I’m curious about your approach to these characters’ interiority. They are so much more than their circumstances, yet those circumstances are inescapable. How did you go about blending the demands of historical accuracy with the more intuitive work of creating an emotional landscape that resonates beyond time and place?

Sze-Lorrain: All the women in my stories are composite characters. To better prepare myself for historical authenticity, I conducted interviews with Shanghailanders from the former French Concession. I read diaries and consulted photographs from many archives, both personal and public. I’ve based much of my setting descriptions on my memories of Shanghai, Beijing, Nanjing, when I was there during the 1980s and ’90s.

I also visited specific museums and sites in Paris, New York, and Singapore. I was keen to include details of art and architectual history in my fiction. In one of the stories, “The White Piano,” for instance, the protagonist Willow visits the Louvre, after waiting in vain for her “fixer” Gaspard to appear:

Feeling let down by the futile wait, Willow ordered a spiced orange salad with mint and vanilla and lingered at the café. From the arcades of the Louvre, where she sat, the view was crisp and beautiful. On a whim, she decided to seek out the gallery of Baroque paintings, and, in particular, something that had been on her mind for months.

According to the caption, the “monumental equestrian portrait” of Chancellor Pierre Séguier was painted by his protégé, Charles Le Brun, whose legacy was eternalized by his architectural decor genius of Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte, the Louvre, and Versailles. The painting itself, she read, had a turbulent history: confiscated at the end of the French Revolution, it had hung in the city hall of Troyes until reclaimed by the descendants. Later one of them—a baroness—kept it in hiding until her death in 1938. Willow was puzzled: why turbulent? Confiscated, yes, though being reclaimed by the descendants and then kept hidden seemed quite reasonable. What was hidden to one was safe to another.

Willow inspected Pierre Séguier up close. He stared straight into her eyes, but she couldn’t tell from the oil painting if she liked Chancellor Séguier, or even liked the look of him. He was trim, with thick eyebrows and a moustache, and he wore a long robe of imperial yellow. One part of her thought he appeared pompous; the other part saw it as the grandeur of, as the caption stated, “neither a warrior nor a conquering hero” but of an “enlightened” patron and statesman. Who knew if women of that époque had seriously considered such a man young and handsome—he simply manifested social status. The year was 1660. Shown on horseback with six pages at his feet, Pierre Séguier was parading at the entry of Louis XIV into Paris—a theatrical mise-en-scène of a dignified person in “measured harmony and interplay of posture, reminiscent of the ballet.” Right in the center of the portrait, the chancellor appeared to smile but with reticence. Was it seduction or pretense?

Observing her proximity to the painting and the way she scrutinized it, a group of Japanese tourists began to bustle in Willow’s direction, cameras at the ready. She turned around and couldn’t help but laugh. “Do you know why I’m looking at this portrait?” Willow asked the visitors. A woman with a white Chanel bag shook her head.

“I live at a hôtel particulier at rue Séguier, and this distinguished man is Monsieur Pierre Séguier,” said Willow. “I’ve a stingy landlord called Le Cordier, who lives on the first floor. And a paranoid neighbor, Monsieur Fournier, on the top floor. They have grand pianos, but they don’t know how to play. Monsieur Fournier sleepwalks in the entrance court. He needs Monsieur Le Cordier to put him back to bed. What’s wrong with these wealthy old men?”

Dapanas: Fascinating! The excerpt you just shared is a potent example of how your oeuvre exists at an intersection of poetry, fiction, translation, calligraphy, and music. I’m interested in how these art forms converse within your creative process. Does a musical structure ever find its way into a novel’s rhythm, or does the precision required for poetry sharpen your line during translation?

Sze-Lorrain: Yes, music plays a role in all aspects of my writing life, probably on a more unconscious level, and certainly not theoretical. I do what I can to incorporate breathwork in writing. Poetry helps me with imagery and sharpens my line in prose—I listen to every word and sentence—whereas translation teaches me to be a closer reader and to gauge distance between the text and myself more creatively.

Dapanas: Congratulations on the publication of your new translation of Zhang Zao’s selected poems, Mirror. As one of the Five Masters of Sichuan, Zhang’s work from the 1980s presents a unique expanse. I’m curious about the arc of your engagement with his poetry. What was the initial “spark” that compelled you to translate it? And having now lived so closely with these poems, how has the conversation between his artistic sensibility and your own evolved?

Sze-Lorrain: The polyphonic voices, intertextuality, and cross-cultural influences in Zhang Zao’s poetry make it distinct from the work of other Chinese poets I’ve translated so far. His long and sequence poems appeal to me.

The fact that Zhang is no longer around means that I have to research differently and adjust to another solitude. This project has taken fourteen years, so extracting myself from his voice needs a bit of effort and patience. I always try to translate poets whose work and sensibilities differ from mine.

I like the idea of a conversation. For example, one of my own poems, “I Wait for the Ruined Elegance,” from my third collection, The Ruined Elegance (Princeton, 2016), contains a first line after the last verse of my translation of Zhang Zao’s signature piece, “Mirror”:

Plum blossoms comb the southern mountain. Maybe

winter,

maybe spring. What can the difference

give a bystander? If

only swallows mend the wind, another way to choose—

tree to tree, grievance

by grievance. I watch

the sun turn from a sphere to a palace. Burning,

but not disastrous. Soon, or

now, my gaze

will break. I want to honor

the invisible. I’ll use the fog to see white peaches.

Dapanas: Zhang’s anglophone debut feels like a complex architecture: one where a reader might turn a corner and encounter the rhythmic tension of the Tang poets, then find a room of Zen-like bareness, or a corridor where Kafka or Marina Tsvetaeva wait for a dialogue. I’m thinking of the pulsing hand and the dream within a dream in Zhang’s “The Prince of Chu Dreams of Rain,” or the exile’s lonely gaze at a “cloud sky” that could be either supplication or survival. Given this symphonic convergence of traditions and philosophies, it brings to question the act of translation itself, not only between languages but also aesthetic and philosophical worldviews. How did you see Zhang as this singular poetic voice drawing from such diverse sources?

My definition of translation isn’t only between languages but the remapping of one imagination to another.

Sze-Lorrain: You’re right about Zhang Zao’s work: It’s eclectic, punchy, full of surprises. He too was a translator and had worked on Mark Strand, Seamus Heaney, Paul Celan, among others.

My definition of translation isn’t only between languages but the remapping of one imagination to another. I seek to translate silences and look for the best quality of silence, no matter how complicated the text.

Other than the fact that Zhang wrote in Chinese, I don’t see his poems as a form of “Chineseness.” Quite the contrary, he’s a very international poet. A large part of his poems contains sources, places, and themes related to Europe and the US. Beyond allusion, his work runs in dialogue with Kafka, Keats, Whitman, Tsvetaeva, Baudelaire, Schloss Solitude, Tübingen, New York . . . The list is long.

Dapanas: An intriguing portion of your work resides in translation. Having moved between languages, both from the French and from several Chinese poets into English, I’m curious about the metaphor often used to describe this role. Do you find “translator-as-cultural-ambassador” to be a useful one, or does it perhaps simplify the more intimate alchemy of the act?

Sze-Lorrain: I don’t think about labels or identity politics but focus on each word, line, poem, paragraph when tackling a piece. But I don’t have a problem with translators being perceived as “cultural ambassadors.” They facilitate dialogues, make boundaries and walls disappear in so many ways, sometimes visibly, mostly invisibly. It’s an admirable mission and vision.

Concertizing makes me aware of time and immediacy, which I practice in writing (and in life): Every word must count.

Dapanas: Rereading Dear Chrysanthemums, I’d say there’s certain music that seems to echo all throughout the novel. In the titular story, the guzheng becomes a lifeline, even alter ego, amid persecution for Madame Mei: “If not for music, our guzheng tradition, I too might have taken my own life.” How has performing the zheng as a harpist and concertist influenced your portrayal of music as survival in the novel?

Sze-Lorrain: Musicians and performing artists are more vulnerable to the public than writers and translators. They need to confront the audience. They can’t hide. They must be present in that very instant. They can’t revise or repeat time. Performance teaches me emotional honesty and authenticity at their best. What you see is what you get.

I try not to conceptualize or intellectualize the experience of music-making. There is a Chinese saying, Onstage three minutes, offstage ten years’ work. Concertizing makes me aware of time and immediacy, which I practice in writing (and in life): Every word must count. But who knows how much time has gone into each word?

Dapanas: You also venture into calligraphy, adding more layers to your already-multifaceted career. In Zhang Zao’s “Grandpa,” the grandfather’s calligraphy evokes what you’ve described in “Neither an Elegy Nor a Dream” (from Dear Chrysanthemums) as a “noble face, too discreet to weep.” In his “Edge,” the persona “practices fine but delirious calligraphy.” I understand there’s restraint involved in brushwork. So would you say such restraint is parallel with the breath and flow of reading and rendering the verse of Zhang?

Sze-Lorrain: Calligraphy is about the qi. It physicalizes the essence of poetry. I see each artistic expression as a way of life rather than as career. Through calligraphy, I have to undo what my eye thinks it’s seeing and to live with spaces without “language,” even if, on the surface, calligraphy seems just about “words” or their visual representation. No discourse, no narrative. Just the fact of what it is. I too learn to create negative space and volume more freely. It isn’t the ink stroke but the spaces around and through it—the spaces/worlds each stroke has created, their various silences and meanings.

Calligraphy is about the qi. It physicalizes the essence of poetry.

I believe Zhang Zao is influenced by calligraphy too. His father is a calligrapher, his grandfather a martial artist.

Dapanas: Looking ahead, what might your readers anticipate from your evolving body of work in the near future?

Sze-Lorrain: I don’t like the buzz of forthcoming publications or any speculation. But you’re right that change is a constant in my work. Once something works, I look for another problem to solve. I don’t wish for a “one-size-fits-all” success formula.

Moving forward, I’d like to address the threats of political instability and lack of collective presence to literary imagination. I’m interested in creating multiple perspectives and using more than one artistic medium to help us work through uncertainties or conflicts. I say “work through,” not “go around” or “avoid.” As for the future, what is it? The passing of a cloud.

October 2025

Fiona Sze-Lorrain is a writer, poet, translator, and editor who writes and translates in English, French, and Chinese. She is the author of a novel in stories, Dear Chrysanthemums (Scribner, 2023); five poetry collections, including Rain in Plural (Princeton, 2020) and The Ruined Elegance (Princeton, 2016); nineteen books of translation; and three coedited anthologies of international literature. Longlisted for the 2024 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, she has been a finalist for awards such as the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Best Translated Book Award, and the Derek Walcott Poetry Prize.