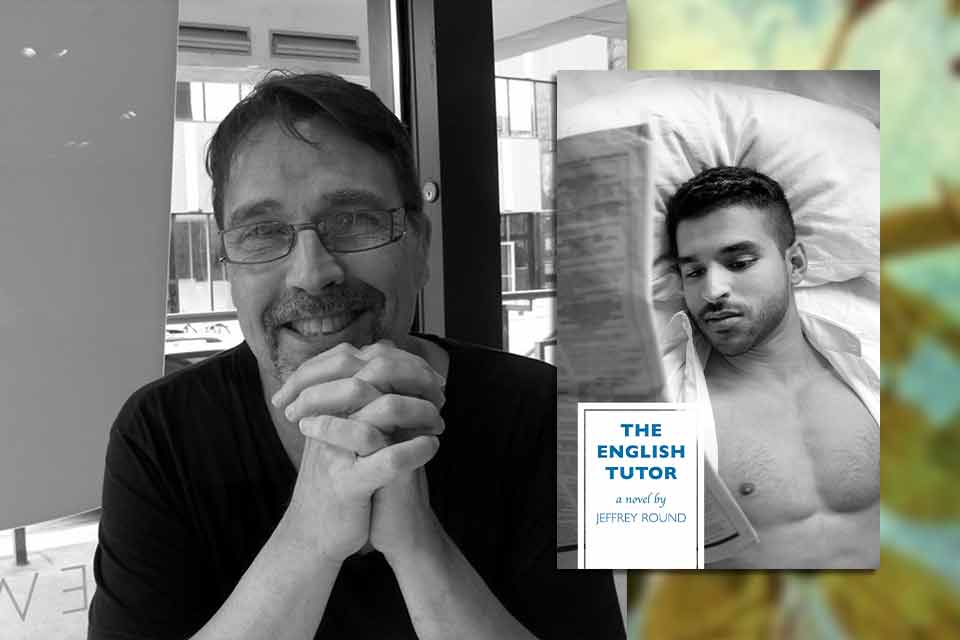

Pursuing Autofiction: A Conversation with Jeffrey Round

Jeffrey Round is an award-winning Toronto author, playwright, songwriter, and filmmaker. His books include the seven-volume Lambda-winning Dan Sharp mysteries, the Bradford Fairfax comic mysteries, the Re-Lit nominated poetry collection In the Museum of Leonardo da Vinci (edited by Keith Garebian), and the acclaimed war novel The Honey Locust. He directed Agatha Christie’s stage classic, The Mousetrap, for three of its record-breaking years at Toronto Truck Theatre. His 2022 music video, “Gone Again,” won the Luis Buñuel Memorial Award, and his recent novel, The Sulphur Springs Cure, a historical whodunit from Cormorant Books, was called “an extremely satisfying reading experience” by the Toronto Star.

Keith Garebian: What preparation do you usually take before starting a novel? Do you begin with a theme, a character, a setting, or even just a single dramatic image?

Jeffrey Round: It might be fair to say I begin with a sharp intake of breath. All of the above are important to my writing, but I know when I feel something that hits me. The Honey Locust, for instance, took shape while I sat on my back porch under a locust tree, thinking about nothing. I felt a moment of release, a kind of peace, and understood that it was not just about me but about a character I’d had in mind for years. I knew she was a photographer or an artist, but nothing more. As the conflict in the former Yugoslavia (1991–95) played out each night on the news, I sensed somehow she would be attached to that. That moment became the final scene in the book. And, ironically, the first scene was the last to be completed. So, in this case, the baby was a breech birth, coming out backward. Because of the complexity of the subject, and the region’s seven-hundred-year history, the book took more than ten years to research and write. And yes, there were days when I thought it would never be published.

Lake on the Mountain, the first Dan Sharp mystery, began with an acquaintance telling me about the suicide of his boyfriend one summer, followed by an unrelated visit to the actual lake in Prince Edward County the next. Again, somehow, in my mind, they connected. A year later, I was driving along listening to a jazz CD and heard two people arguing in my head about whether you could tell by the playing if a horn player was black or white. They turned out to be Dan, who is white, and his best friend, a Black man named Donny. I put that scene in the first chapter, at Dan’s son’s birthday party. It was a good choice because later, mysteriously, the solution to the mystery turned out to revolve around the birthday of another son. My best writing comes that way. It often feels like I’m taking dictation. I turn off my left brain, aka “the critic,” and let my right brain fly. There’s no outward reasoning to it. That is just how I write: by instinct.

My best writing comes that way. It often feels like I’m taking dictation.

Garebian: Your previous novels can be roughly divided into two categories—noir-edged Dan Sharp mysteries and Bradford Fairfax mysteries with touches of Armistead Maupin. You do have three significant stand-alone novels: Endgame (a sort of Agatha Christie reboot), the war novel The Honey Locust, and The Sulphur Springs Cure that begins as a period-piece Christie fiction but has a metaphysical twist. At their best, the novels mix modes in fascinating ways while distinguishing themselves by attention to characterization, dialogue, and setting, with The Honey Locust moving among Ontario, the former Yugoslavia, and Mexico, while Endgame takes place on an island off the coast of Seattle. Is this because you accept variability as your normal? And does setting determine form in your case?

Round: Setting is extremely important. In a sense, it becomes a character in each book. As mentioned, Lake on the Mountain is an actual place, one with spooky overtones because of the seeming illogic of the placement of the lake itself high up on top of a mountain, with no visible incoming streams. With Endgame, I invented Shark Island, but the main structure on the island, a postmodern mansion, is loosely based on a real building not far from my home. (It’s on the northeast corner of Harcourt and Jones, if anyone wants to track it down.) Again, Sulphur Springs is a real place near Ancaster, and it was while walking the trails that the story “sprang” into my consciousness. I love to travel, so variability is a norm for me. I find immobility disconcerting.

Garebian: I know that you have been published by several Canadian presses, so what role does an editor play in your novels prior to publication?

Round: There has never been any editorial instruction prior to writing the novels, because I almost always sell books after I’ve finished them. The only time this was not the case was with the last three books in the seven-book Dan Sharp series, which Dundurn asked for sight-unseen, apart from a cursory look at a rough draft of the fifth book. The series had already won a Lambda Award and been nominated two more times, so I guess they felt I knew what I was doing.

Setting is extremely important. In a sense, it becomes a character in each book.

Garebian: Your new novel, The English Tutor, is a game-changer. Reinforcing your familiar literary features, it takes readers into more dangerous territory. From a quick search of the internet, I discovered significant novels about gay Middle Eastern Muslims. For instance, God in Pink is by Iraqi-Canadian Hasan Namir and is set in Iraq. Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying carries us into Morocco. Saleem Haddad’s début novel, Guapa, spins a story about a young gay man living in what seems to be a version of Syria. Zeyn Joukhadar’s The Thirty Names of Night concerns the mysterious disappearance of a Syrian immigrant painter but is set chiefly in Manhattan and Michigan, while No Knives in the Kitchens of This City, by Khaled Khalifa, describes a Syrian hell. All these novels show that there is no single gay Arab experience, though there are some commonalities between Western and Arab gay lives. As far as I have been able to tell, The English Tutor is the first novel (in English) about a gay Middle Eastern Muslim set in Libya. Why and how did you settle on this story, and why Libya as its setting?

Round: I’ve had a number of Muslim friends and colleagues, which has afforded me insight into aspects of Islamic culture in a general sense. As well, I have dated four Muslim men. (Question to self: is “dated” an old-fashioned term?) I quickly learned their various levels of willingness to engage in a relationship. As we know, homosexuality is haram, or forbidden, under Sharia law. Only one of the men was completely, and I might add defiantly, out with his community. Although born in Pakistan, he was highly westernized, while the others were still very much conditioned by their upbringings. It was, needless to say, an exercise in frustration trying to form full and honest relationships with these men, apart from the first, who remains a good friend.

One of the men who proved most difficult was also one of the most intriguing. He was raised in Libya and had fought in the war. It was through him that I learned the history of the country’s conflicts, many of them still ongoing. It was his father, whom I met online, who first encouraged me to write about these struggles in the hope that the world at large could know and understand what it was like for Libyans.

Garebian: Opening with a flashback where a pile of stones conceals the body of his Libyan lover who was murdered by Islamic fundamentalists, your novel is about characters and lives fractured by war, religion, and societal biases. Narrated by Geoffrey Manderson, a self-styled aesthete who, feeling bored and out of touch with life, has returned to Toronto after an extended stint in Europe where he traveled from country to country by teaching English to “bored, wayward children of the middle classes” from backgrounds as pampered as his own, it is a story of a doomed intercultural love. Geoffrey’s European séjour brought him merely temporary relief from his platitudinous mother, “her Britishness shining through with hints of snobbery like glints of semi-precious stones extruding from a slab of basalt.” She nags him continually about not taking his future seriously and about the need to start a family. His deceased father was a typical corporate executive and a chronic philanderer, from whom he had a small inheritance to feed his existential discontent. Geoffrey’s closest friend is David, a former go-go boy turned bookkeeper, who knows how to read him, as well as his fatal love for Yusuf.

Jeff, you don’t rush things in the plot. You set up the novel’s principal themes expertly, showing how Geoffrey becomes an English tutor to a group of Libyan war refugees, all damaged physically and psychologically in their civil war back home. Shy Hassan, with the looks of a matinée idol, is an amputee in a wheelchair; Abdel, a large, gruff double-amputee, is a former mushroom farmer with “the soul of a sensitive man”; and, of course, Yusuf, with a look of wounded beauty, who keeps his damaged left hand tucked into his jacket pocket and is chronically nervous about his interactions with Canadians.

How much of all this material comes from your own direct experience with wartime refugees from the Middle East as well as your own family history?

I love to travel, so variability is a norm for me.

Round: The question intrigues me greatly, not just with regard to this book but with the boundaries between fiction and reality in general. With The Honey Locust, I consciously set out to write a book that was not autobiographical in any way. Although a war novel, on the most basic level, it’s a story about three sisters struggling with their mother’s emotional unavailability. My brother Mark pointed out that I had really written about him and our brother Brian—but as girls instead of boys, having problems with their mother instead of, as in our case, their father. So, it is with some hesitation that I say the family in The English Tutor is entirely fictional, if such a thing is possible. In this, I intentionally pursued a literary genre known as autofiction, which, loosely speaking, appears to offer a constructed form of autobiography. The protagonist’s name is the Teutonic spelling “Geoffrey,” while mine is the English “Jeffrey.” I did this as a sort of game—not purposely to confuse the reader but to deepen the level of interest in the characters. In effect, it becomes a sort of “Is he or isn’t he?” game. I find myself drawn to writers whose work hints at a similar technique, especially if I am interested in the writer as a person—Proust, for instance. Did he write a memoir, or did he write one of the world’s most enduring novels, or both at the same time?

As for my experience with wartime refugees, it was based loosely on a small group of men who came to Canada for physical rehabilitation following the Arab Spring uprising, supported, as far as I understood, by an agreement between governments. I didn’t set out to write about them, nor did I teach them English, but found them eager to talk and equally found their stories fascinating, particularly as none had been a soldier prior to the war. They were, for the most part, ordinary men who got involved in their country’s conflict, suffering greatly—physically, emotionally, psychologically—as a result.

Garebian: I am very impressed by the way you have structured the fiction. The story swells slowly, then contracts, and swells again. The affair begins with just a glimpse. Geoffrey’s first sight of Yusuf is of a young man in a leather jacket, who has a mysterious smile and a mane of curly hair.

But as the English classes begin, there comes a narrative temperature change, with Yusuf’s first sexual move, and the growing complications of their relationship. Yusuf suffers from chronic nightmares, becoming edgy and obsessive but at the same time “eerily vacant,” as if he has forgotten who or where he is. He is an anomaly: a Muslim who wants to please his tradition-bound family while also being drawn to tempting Western luxuries. Part of him wishes to return home because he feels guiltily estranged from his family; part of him wishes to stay in his new land where he could be free to be who he really is. Geoffrey slowly realizes that his own world is not and could never be Yusuf’s. “He belonged to the dust and sand, to mosques and muezzins, and a religion mired in the Middle Ages. And to war—most of all to war. He’d given his soul and body to the fighting. That was his siren call. I was merely the distraction from his real love, fighting.”

After an initially unhurried, enticing rhythm, the plot speeds up in the second half, as Yusuf feels like the caged zebra finch he has bought, a beautiful bird that escapes one day. Nothing is sensationalized. Yusuf’s family is revealed quietly, with each character allowed his or her own private truth, just as Benghazi’s civil unrest and anomalies are revealed through an unedited video on a laptop. How Yusuf’s own death comes about in Benghazi is wrought in moments of skillfully modulated tension, starting with the appearance of Moustafa Farouk, a high-ranking Libyan official in Toronto, who has the sting of a deadly scorpion; Yusuf’s conflicted love for his family and country; the nefarious plot by his brother Omar; his betrayal and murder by stoning; and Geoffrey’s eventual blazing grief. Yusuf’s prophecy, “Geef, one day you are going to kill me,” comes true, and in a manner that tests the scope of resilience, passion, and courage to be true to oneself.

Do you think this novel offers hope to gay individuals to live more courageous lives?

Round: We all have various levels of personal courage, depending on the situation and our will to change our circumstances. Likewise, there are varying degrees and styles of oppression—societal, political, religious. I grew up in homophobic times, although I never felt my life was threatened by others. Instead, I turned the hatred inward until I found myself contemplating suicide on a regular basis. I was in my late teens by then. By chance, when I turned twenty, I met another gay man who helped me face my fears and come out, first with friends and later with family. My coming out was not easy. I had friends who rejected me, including a Muslim man I now believe was gay, as well as a straight man I considered one of my two closest friends at the time, though he later came around after a year of thinking things through. My other best friend, writer Dawn Rae Downton, was more accepting. My parents (I was told under no circumstances was I to mention the fact to my younger brothers) were not supportive at first, but they, too, later came around and accepted me, though the feeling of having been judged stayed with me quite heavily for years. If you don’t take the first step, you’ll never know where it might lead.