Anthologizing Polish Short Stories: A Conversation with Antonia Lloyd-Jones

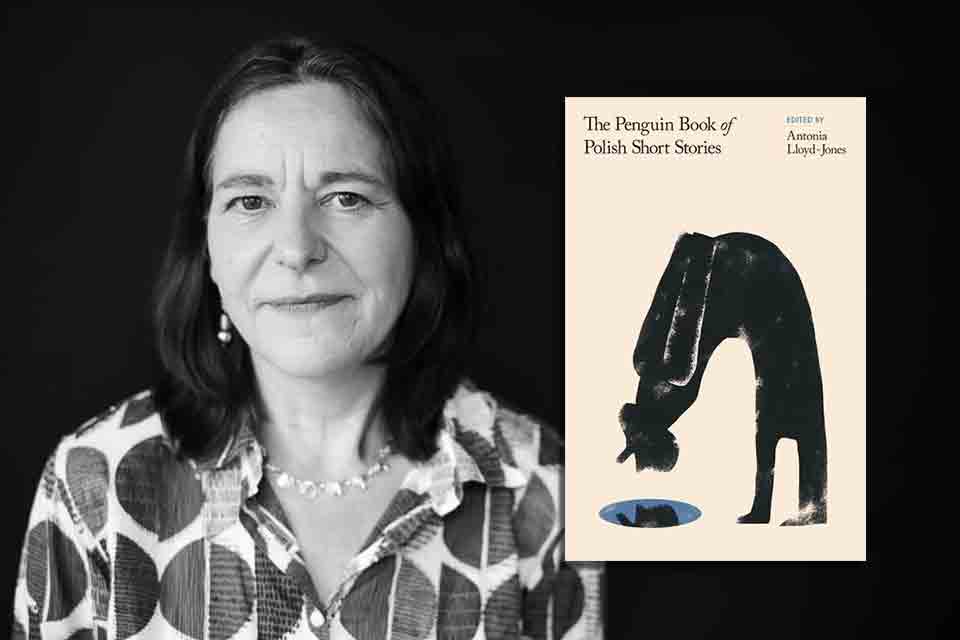

Antonia Lloyd-Jones is a translator of Polish into English and the 2018 winner of the Transatlantyk Award for the most outstanding promoter of Polish literature abroad. She is widely known as a translator of Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk: her translation of Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2019 (see WLT, Winter 2019). For ten years, she was a mentor to young translators through the Emerging Translator Mentorships program. Her most recent books include nonfiction works such as Witold Szabłowski’s What’s Cooking in the Kremlin (2023) and fiction such as Voracious, by Małgorzata Lebda (2025), and Tokarczuk’s The Empusium (2024; see WLT, Jan. 2025). She curated the collections Warsaw Tales (2024; see WLT, May 2025) and The Penguin Book of Polish Short Stories (2025), which is the focus of our conversation.

Sara Bielecki: How did this anthology of Polish short stories come about?

Antonia Lloyd-Jones: Years ago, I discussed the idea of an anthology with the translator Bill Johnston. We had some thoughts about who might be in it, but it would have been hard to interest a publisher, so we dropped the idea. Then along came Penguin with a commission for me, within their short-story anthology series. They have been commissioning translators to produce these books: the more recent ones include Spanish short stories, compiled by Margaret Jull Costa; Italian, by Jhumpa Lahiri; Japanese, by Jay Rubin; Korean, by Bruce Fulton; and Bengali, by Arunava Sinha. So I was commissioned to compile the Polish one.

Bielecki: There are thirty-nine stories in this book, and the work of twelve translators (yourself included). Beyond the stories, there is also biographical information about each author, a preface, an introduction, a historical timeline, and a rich bibliography. Putting this together was a tremendous amount of work. How long did it take you?

Lloyd-Jones: All in all it was about four years’ work. There was a deadline of course—which I had to get extended!

Bielecki: Could you tell me about the mechanics of putting it together?

Lloyd-Jones: At the start, I was given a deadline, a budget, and a limit of 190,000 words. That had to include everything—the preface, the introduction, a foreword for each story, the biographical and permissions information, and a further reading list. Polish usually comes out roughly 30 percent longer in English translation, so it can be hard to estimate a word count. I created Excel charts with all the wordage on them, and I was constantly trying to work out how many words I had left. Quite often, I ended up trading: I sometimes chose a shorter story by an author I knew I wanted to include to “buy” the space to include another. It took a lot of planning. There was also the issue of permissions—we did a lot of work to track down all the rightsholders. The Polish Book Institute helped me and the publisher enormously. Finally, we managed to get thirty-seven out of thirty-nine of them fully cleared.

Bielecki: The process of finding the stories must have been something of an excavation.

Lloyd-Jones: On every trip to Poland, I would do some research for the book, which was an enjoyable task. I’d tour the stalls in Warsaw where they sell old books, and I’d go to secondhand bookshops in every town I happened to visit. I found a lot of tatty old books! I did an excellent raid on a secondhand bookshop in Zamość with two former mentees from the Emerging Translator Mentorship program. They were very helpful in finding things for me.

Deciding on the contents was the hardest part. I consulted various people in Poland, including authors, literary critics, and academic experts. I started with a very long list of ideas, and they helped me to reduce it as well as to consider authors I had overlooked. There were authors I knew I wanted to include, but in some cases, I couldn’t read every story they had ever written within the deadline. With a time limit, you’re always constrained. So, once I had a few collections by a particular author I would mentally say to the author, “OK, this is all I can read, show me your best with these three books.” And at some point, a story would leap out of the page and say, “It’s me!” That was the case with the story “The Phonograph,” by Jan Parandowski, whose work I love.

Bielecki: That was one of the eighteen stories you translated yourself. Please tell me about how you incorporated the work of other translators.

Lloyd-Jones: The publisher gave me the option to buy in some existing translations and commission some new ones. The work of the best-known authors, like Bruno Schulz and Stanisław Lem, has already been translated, so I bought in existing translations by those authors and also some translations by less famous writers that I knew had been published in journals but never in book form. I commissioned twelve translations. Altogether it was a fantastic opportunity to showcase the work of some of the best translators, including well-established people like Bill Johnston, Bill Martin, Ursula Phillips, Jennifer Croft, Stanley Bill, Anna Zaranko, and Madeline Levine, as well as some of my own former mentees, like Sean Gasper Bye, Eliza Marciniak, Tuesday Bhambry, and Jess Jensen Mitchell, who translated the first story, “Love and Life in the Hen House,” by Irena Krzywicka. The translators also contributed to choosing the stories they would translate and did invaluable research for me. Unfortunately, I soon ran out of money, as the budget had to cover permissions as well as translations, so I translated the remaining stories myself.

Bielecki: Adding to your workload!

Lloyd-Jones: Yes, but at that point the Polish Cultural Institute stepped in with some extra funding, which meant I could commission some of the translators to write their own story forewords. So that took some of the pressure off me. I didn’t have to edit the translations either. That was done by Ka (Kaliane) Bradley, who coordinated the whole project for Penguin and is also known as the author of the novel The Ministry of Time. The final element was the preface, written by Olga Tokarczuk.

Bielecki: In the preface, she describes this undertaking as a “seemingly impossible challenge,” which sounds about right! What were your main aims?

Lloyd-Jones: I wanted to include authors who haven’t been translated into English before. Of course, I had to include the greats, such as Gombrowicz, Schulz, and Lem, who are already known in English, but there are many others who have been overlooked. Some, like Tadeusz Konwicki, have been translated up to a point, but others, such as Stanisław Dygat or Kornel Filipowicz, barely exist in English, if at all. I also put a big effort into including as many women writers as possible. One-third of this anthology is by women (thirteen out of thirty-nine stories), but my research implied that there’s a huge gap, as in the communist era they don’t seem to have been published, or at least not their short stories.

Bielecki: Has the collection helped in raising visibility?

Lloyd-Jones: Yes. Ursula Phillips, who translated the story by Maria Kuncewiczowa, “Covenant with a Child”—which scandalized the public when it first appeared in 1927 for its unsentimental depiction of early motherhood—is now going to translate a novel by Kuncewiczowa into English. The story in the anthology helped bolster the publisher’s interest.

Bielecki: Kuncewiczowa is not the only female writer in the collection to have ruffled feathers on the Polish literary scene. One of the contemporary authors you also have is Dorota Masłowska, who’s known for winning Poland’s most famous literary award, the Nike, with the startling novel The Queen’s Peacock, when she was just twenty-three. In the introduction to her story in the anthology, “The Isles,” she explains how she was inspired to write it because you had reached out to her.

Lloyd-Jones: Yes. I wrote to her asking her if she had ever written any short stories, and she said no. She was away from home on a writer’s residency in Switzerland, staying at a converted monastery where she felt a bit isolated, and ended up feeling an urgent need to write. She remembered I had asked her for a story—and so she wrote “The Isles.” What’s really wonderful is that eventually she turned it into a whole novel, The Magic Wound. She told me I was the book’s fairy godmother!

Bielecki: There is something of a mood of rebellion about this anthology as a whole, when it comes to how you’ve organized it. There are sections titled “Animals,” “Children,” “Women Behaving Badly,” “Men Behaving Badly,” among others. Tokarczuk called it a “rebel order.” How did these categories come about?

I decided to provide a more balanced view of Polish literature, in particular to show its humor.

Lloyd-Jones: For my research, I read several anthologies published in the 1970s, and most of the stories were about the war. I found that very depressing, and not how I think of Polish literature. Unfortunately the stereotypical image among foreign readers is of doom and gloom, the war and the Holocaust. I decided to provide a more balanced view of Polish literature, in particular to show its humor. I began with a set of themes I wanted to cover, originally including “Sex,” “Children,” “Animals,” “God,” and “Village.” Later, I realized that animated things would make better category headings for the stories. Eventually, this developed into a sort of revolution—anthologies of this kind tend to be organized chronologically, for example, but I’d be concerned that readers might avoid the older stories; so I broke them up into slightly perverse categories to intrigue the reader, and also to give each of them a chance to find something personally appealing for starters, and then move on to things they might not have chosen for themselves.

Bielecki: We do often have preconceived ideas about what will interest us as readers.

Lloyd-Jones: The way I’ve organized the stories is deliberately a bit anarchic: it’s not to be taken too seriously. But this way, if you don’t want to read about war you don’t have to. I’ve put “Soldiers” in their own box, and the “Survivors” section also refers to the war and the Holocaust; you can only write about it if you’ve survived it, so I prefer to call it survival. That section includes a tragic story by Ida Fink, about a girl forced to buy Aryan identity papers with her virginity.

The way I’ve organized the stories is deliberately a bit anarchic.

Bielecki: The categories could also be considered quite porous. In the “Surrealists” section, we have the story “An Enigma,” by Stanisław Lem, which consists of a discussion between some religious robots! The story is hilarious, but reading the introductory remarks about Lem’s life, we learn that he, too, was a survivor.

Lloyd-Jones: Lem was fascinating. He loved machines. He used to receive foreign currency for his royalties from abroad and would take his family on trips to Croatia where he would buy gadgets, but he never read the instructions, so he’d try to make them work but they usually broke! He was also obsessed with cars. But he wouldn’t talk about the war period, which he spent in Lwów. He was Jewish and was lucky to survive. He witnessed some terrible incidents. There are excellent books by Wojciech Orliński and Agnieszka Gajewska that explain how the experiences he wouldn’t talk about are hidden in his literary works.

Bielecki: Did you ever struggle to work out which category the stories belong to?

Lloyd-Jones: I had fun working out which went under which heading—for instance, the Gombrowicz story “The Tragic Tale of the Baron and His Wife” is in the section titled “Women Behaving Badly,” though in fact it’s the men in the story who behave badly, but the woman gets the blame!

Bielecki: Overall, it sounds like creating an anthology like this makes for a joyful, but also stressful, experience.

I couldn’t help worrying about the responsibility involved in compiling an anthology that has to sum up a whole country’s literature.

Lloyd-Jones: I couldn’t help worrying about the responsibility involved in compiling an anthology that has to sum up a whole country’s literature. How often is there an opportunity for such a book to appear? But I hope I have fulfilled my two main ambitions: to give readers a chance to explore Polish literature and to inspire other translators in the future.