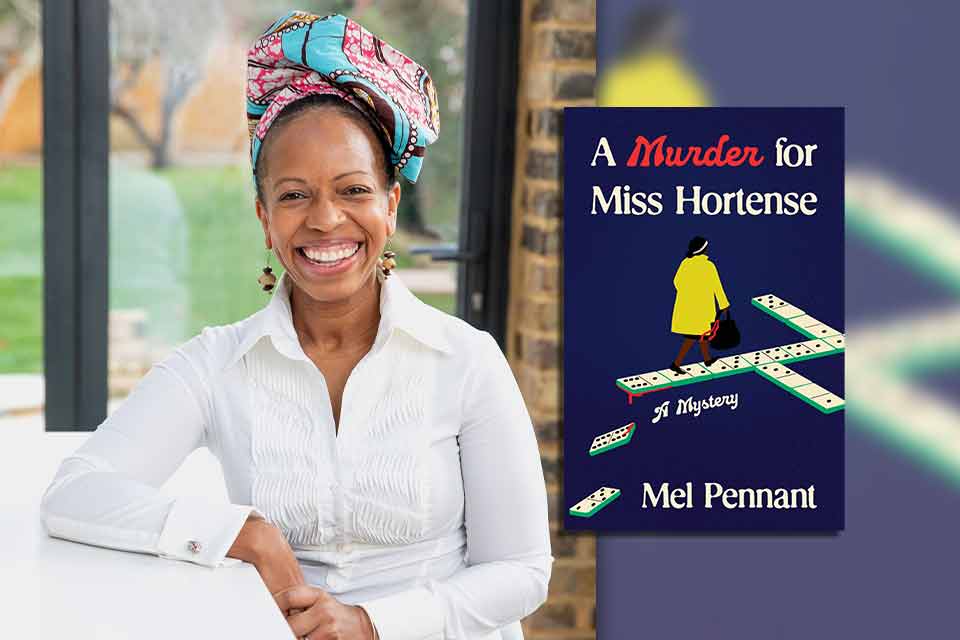

“Never hang your head, girl child, raise it up high like a so”: A Conversation with Mel Pennant

Mel Pennant, known primarily as a playwright and screenwriter, published her debut novel, A Murder for Miss Hortense (Pantheon) in June 2025, the first in a planned mystery series starring a retired nurse and amateur detective who is both truth-seeker and truth-teller of the first order. Within a time spanning the early 1960s until 2000, Pennant brings to life a tight-knit community of Jamaican immigrants known as the Windrush generation, a group from former British colonies in the Caribbean who settled in the United Kingdom after World War II. Central to the novel is the Pardner Network, a financial arrangement of friends and neighbors who form an investment group to pool their money and make loans to one another on a rotating basis. In the novel, Miss Hortense, once a leader of the Pardner, was unceremoniously ousted from the group thirty years ago, though why and how is part of the mystery to be solved. A force to be reckoned with as well as a woman with secrets and demons of her own, Miss Hortense proves throughout trying and troubling circumstances that she lives true to her mother’s advice: “Never hang your head, girl child, raise it up high like a so.”

The following conversation occurred via Zoom and email during July and August 2025.

Renee H. Shea: In so many ways, A Murder for Miss Hortense feels like a love letter to Jamaica. It’s dedicated to your grandparents, “Miss Dolly, Baby, Bobsie and John, and to your whole generation.” Would you share a little about them?

Mel Pennant: I’m very happy to talk about them. My paternal grandparents raised me for a long period of time during my childhood, so I was very close with them, but close with both sets of grandparents. Everyone lived proximate to each other, and for me, it was just normal having my grandparents in my life. I think with grandparents you can sometimes neglect them a bit; as you’re growing up with them, you see these boring older people. But as I got older, I had a realization of how amazing they—and their whole generation—were to come to the UK at a time when there was quite a lot of hostility, yet they settled and created a life for themselves and for their future generations. I am just in awe of them.

My grandmother Miss Dolly was this vibrant character who had a way of drawing people to her. She passed away several years ago, but I went to an event recently where there were some people that I didn’t know, but they knew my grandmother, and they said, “Oh, of course, I remember Miss Dolly, she used to invite people round to her home.” She had a real impact on people, often through humor. I felt I could talk to her about anything; she wasn’t judgmental. She was a huge storyteller, and I would just absorb that.

My [paternal] grandfather was this really cool dude who was very wise. I can see him on his couch now. We all had to watch cricket, not that I understand cricket at all, but it was what we did. My other grandmother was also so amazing, so generous to me and my friends. There are lots of funny stories about my mother’s mother; my friends used to call her Super Gran because she was so fit: we’d be running for the bus, and she’d be way ahead of us. She was also a very strong woman; there are all sorts of stories of her chasing my aunts down when they weren’t behaving properly. She wasn’t afraid to speak her mind. So, although Miss Hortense is very much a work of fiction, I feel that a lot of my grandparents’ influences have filtered their way into her.

Shea: One reviewer I read praised the novel in general but said that the “real lagniappe” is the fictional community of Bigglesweigh in Birmingham. It’s a close-knit group, yet with both the usual as well as unusual differences and difficulties. Is this mostly based on where you grew up?

Pennant: No, actually, Bigglesweigh is a fictional place in Birmingham, but I didn’t grow up in Birmingham at all. I grew up in London, and that’s what I know, but I’m really pleased that I didn’t base Miss Hortense in London. People tend to just see the Black community in the UK as having settled in London, a huge metropolis when, actually, Black communities have established themselves, even before the Windrush generation, in [places like] Birmingham, Bradford, and Cardiff as really vibrant communities with depth and richness, and I thought it was important to acknowledge that. The story of Miss Hortense and the Pardner network is one of quite intimate community, and I felt that London would not be able to do that for me—because you initially see it as this huge place filled with lots of strangers and individuals who come together.

There’s a great writer who just published a book called We Were There [How Black Culture Resistance, and Community Shaped Modern Britain, by Lanre Bakare] that is all about these communities that settled across the UK. I feel that by basing Miss Hortense in Birmingham, I’ve been able to touch on the importance of that. In terms of my connection with Birmingham, my paternal grandmother’s best friend, called Aunt Sis, used to live somewhere called Erdington, Birmingham. We would all go there for important events, marriages and that sort of thing, and we’d stay and sleep on someone’s floor. It felt very special driving there in my grandfather’s Triumph. It’s quite evocative to me as a place, just in terms of that richness created by my grandmother and her best friend reconnecting in that space.

Shea: A Murder for Miss Hortense was published almost simultaneously in the UK and the US. Were you at all concerned that some readers, perhaps especially Americans, might be unfamiliar with the history or cultural markers such as the Pardners or the dominoes game and the Jamaican patois and so might be discouraged from reading the novel?

Pennant: I hope not, and it wasn’t a worry for me. Partly it’s sort of selfish because I know [the history and culture] and assumed others would get it. But also, it’s not so unfamiliar that people can’t understand it. If you read the novel and don’t know the history, I think you will still get something from it. Then there’s the opportunity to go and find out more. I think what’s really important for me is that the history this book speaks about is everyone’s history. The Windrush generation came to the UK and settled in places where perhaps there weren’t Black communities before, but the other parts of that community had to integrate with them. So, it feels to me like it’s not just the West Indian community that I described but other communities as well. If that opens a door that enables others to feel they can access it, that’s wonderful. And I think it’s almost a plea to do so. The risk is, always in my writing, that you see these people as “others” in some sense, and they’re not actually—they are us. I think that is sometimes the problem you see on a large scale, even in the current day. Even if I’m showing a bit of the world that not everyone is familiar with, I hope that people will engage and want to delve deeper because I’m talking about all of us.

The Windrush generation came to the UK and settled in places where perhaps there weren’t Black communities before, but the other parts of that community had to integrate with them.

I just love this community and the fun that I have when I’m with them, and I wanted to give that to others. If readers can experience that, then that’s amazing—we can go on this journey together. I’m writing the second book of the series at the moment, and I’m just in my happy happy place!

Shea: Before we get into the heart of the novel itself, I’d like to hear a little about how it came about. You’re a successful playwright and a lawyer by training, so how did the idea for a novel, a mystery novel, come about?

Pennant: For me, a key moment was a play that I was going to write that was going to be nationally toured in the UK in March 2020. But, of course, that was during Covid and lockdown, so the play didn’t happen. We’d spent about four years developing it, and it was going to be a huge deal for me. Unfortunately, there was so much going on obviously in the world and in the theater industry as well, which meant that a number of plays wouldn’t happen. My play was one of those, and there was no bringing it back.

With so much going on, it made me reflect: Am I actually a writer? Is this what I really want to do? Is it me? I went away for a while and thought, I won’t be a writer, I’ll be a lawyer—that’s what I am [by training]. I didn’t write for a bit, but I found that I really need to write; it’s important to me even if nothing gets published. I had some really good people who have invested in my career, and they brought me back into the writing world, saying, Mel, would you do this for me, and I felt loyal to them and did do those projects.

Then, I was mulling and hearing a lot of podcasts with writers talking about how they’d written over lockdown, and it was their introduction to writing novels. They had the space to be able to write, and I thought, Why don’t I try to write a novel, something that doesn’t require actors or directors or theater space? I started to explore that. I had been on a brilliant course in 2018 for playwrights who were considering writing novels. At the time, I wasn’t seriously thinking about writing my own, but I had all these notes. I’d been given an opportunity to see into that world, so I knew, for example, that you needed a literary agent to get to the next step. I started writing historical fiction but realized that writing that novel would take me the rest of my life because I would spend so much time researching. I never quite found the voice.

But I had this idea for a while, I knew the world, and I felt like I could hear the voices already –that was Miss Hortense and the Pardner Network. I wrote about thirty pages and had the name of Nelle [Andrew], my agent, someone I had gotten from the course two years before. I wasn’t sure whether I should send her these pages, but I wanted to know if I was on the right track. Maybe she’d give me some notes and then I’d go away, and that would be wonderful. I sent the thirty pages and a synopsis of the idea. Long story short, she said she would represent me, and that was a really key time. I didn’t have a book, just thirty pages, and she said, “Go away and write again.”

Having Nelle in my space gave me an agent I knew had done amazing things for other authors. She really understood the world I was writing about, and we just kind of wrote the book together. I sent another sixty pages, and she said, no, that’s not the voice, that’s not the book. Then another sixty pages, and she said, “That’s it—and it’s the same sixty pages that you see in the book now—Miss Hortense in her garden pruning her Deep Secrets [roses]. Having Nelle in my space was hugely important, and I feel grateful to her. Everything sort of came together at the right time, to create Miss Hortense and the Pardner Network.

Shea: You must have had some experience with mystery writers. Did you grow up reading mysteries? Who are your favorites or most influential?

Pennant: I did grow up watching mysteries. We’d have Agatha Christie and Poirot on the TV all the time. I can remember on Sunday when Poirot would come on, and there would be this very familiar saxophone music –it would be the going-back-to-school music. But I think in terms of my favorites, I’ll divert a little bit. My favorite writer of all time is Toni Morrison, and I was introduced to her during my A levels, when I was around seventeen or eighteen. We read Beloved as one of our texts. I’ve never experienced anything like it before. It felt like home to me, in a way that I hadn’t read anything that did that to me. The way she uses language—I can’t even talk properly when I speak about Toni Morrison’s work. The poetics of the language, it’s just extraordinary to me. For me, there is mystery in her writing—the light and the dark and the shade. All of that I love.

I can’t even talk properly when I speak about Toni Morrison’s work. The poetics of the language, it’s just extraordinary to me.

When Nelle said after I’d done those sixty pages, no, you need to go back and do another sixty, she asked, “What is your favorite book, who’s your favorite author? Go and read the first sixty pages of that book, study it, understand what is happening in those pages, what is it you love about it.” I did that: I read the first sixty pages of Beloved forensically—everything she does to show us the context, the pain, the joy—and then I came back and wrote another sixty pages. I’m not restricted to the genres that I read. I enjoy murder mysteries because the genre is so broad, but for me, you can show that light and that shade—it's always about what is hidden below the surface, and you can really explore that.

In terms of murder mysteries, Walter Mosley for his description and character-building, and it’s about the community and getting us in those spaces. I looked at quite a lot of Barbara Neely and the Blanche White series. I think she was one of the first Black female protagonists in American murder mystery literature. There’s a lot of social commentary there, and I admire the way you can do that with murder mysteries. The golden age of mysteries is interesting, especially the tropes and how they are used. You see that in Miss Hortense in the drawing room moment when they all come together, and that was very deliberate. Again, it’s those lovely moments we are familiar with, but I wanted to do it in a slightly different way.

Shea: I understand that there was a five-way auction for A Murder for Miss Hortense. That must have been beyond exciting.

Pennant: It was. Again, Nelle made no promises, she said we’re going to go out for submissions and told me all the publishers she was submitting to. I had no sense of what would happen for this book. It’s not a typical murder mystery, I suppose, and I wasn’t sure what the reception would be. To have publishers and editors read the book and really get it was amazing. They would bring whole teams in and start telling me about my characters and who their favorite character was. Literally, I would just sit there unable to speak, gobsmacked; it was like a dream, such a surreal space to be. The publishers who picked it up in the UK and the US were exactly the right publishers for Miss Hortense. They immediately got her, her voice, and even if they were not familiar with the Pardner, they got the essence of her, which is so important. It felt like there was a team I could trust with this really special world.

Shea: This novel is a page-turner, no question, yet it has a complicated cast of characters and a challenging timeline. Although it takes place from the mid-1960s through 2000, it’s not a linear chronology. How did you keep track? I have visions of you in a room with paper tacked up all over listing specific times and events.

Pennant: It was hard to manage. I wanted both timelines—part of what the book is talking about is how important the past is to the present. We have to go back thirty years to understand why Miss Hortense is in her garden by herself as a recluse; in order to understand the importance of the Pardner, you need to go back to its inception and understand why it was so important at the time. That creates a lot of threads you’ve got to keep hold of and do it in a way that is quite compelling and drives the story forward.

I had several spreadsheets—this is when Miss Hortense was born, this is when this happened, etc. But even with all that, we had a brilliant copyeditor, and at one point he was able to identify a plot hole where I had someone who had passed away in the 1960s and I brought them back in the 1990s!

Shea: So many characters are beautifully drawn in this novel, but Miss Hortense is the center: her determination, her homespun wisdom, her boldness, her humanity. What was it like creating her and living with her?

Pennant: There was a long time when I had the idea for her, I knew exactly who she was, I knew how strong she would be—but I didn’t know how to articulate her. I didn’t quite have her voice. I had a very clear vision of Miss Hortense, but I was a bit scared of her. I knew she was going to be this formidable, no-nonsense force of nature, but it was initially through Blossom [her friend] that I was able to find her. I found I could write Blossom so freely—she just flowed, and through her I was able to feel my way into Miss Hortense. I got to see what she would tolerate and what she would not tolerate, so I could actually then bring her to life.

I had a very clear vision of Miss Hortense, but I was a bit scared of her.

Miss Hortense is a very different character from me. I’m a real people-pleaser—and she is so not. She’s in a room and surveying, but not from the perspective of wanting others to accept or admit her. She’s there for a particular purpose, and she’s fine with people seeing and hearing her just as she is. So, it’s a lot of fun actually being that person who I am not.

Shea: There doesn’t seem to be a cynical bone in Hortense’s body. Despite everything that has happened to her, everything she’s seen, she still is emotionally available in many ways.

Pennant: She’s hard and strong and determined to find the truth. But she’s also soft, a realist, and in many ways, that’s my grandmother. It’s all about getting on and how do we go forward. The interesting thing about Miss Hortense is something my inspiring editor [Lisa Lucas] said—which is that she doesn’t have to be perfect. You’re not creating this fantasy character who is a superwoman. She has flaws, she makes mistakes, she’s completely human. But morally, it is important to her to find the truth. And she uses whatever tools are available to her, even if that means confronting a drug dealer.

Shea: I love the recipes, actual recipes for bulla cake, coco fritters, gungo pea soup. Chapter 6, where she is making the gizzados, is, to me, a perfect chapter blending the cook, the detective, and the moral compass. Did you always know there would be recipes, or was that part of the novel’s evolution?

Pennant: Growing up with my grandparents, food was a big part of our lives—a way to bring us together. The spices, the scotch bonnet pepper, the curried goat are all so evocative for me. Walking through my grandmother’s garden where she grew herbs, you could smell it, and it just feels like home to me. When Miss Hortense is making her recipes, it’s her opportunity to mull over a case. I thought it would be a real opportunity to showcase the Caribbean food, and I thought it would be a fun way of bringing what’s home to me into the book.

Shea: Yet there is that deep loneliness in Hortense that makes her ask herself, “But where is home now?”

Pennant: Yes, we see Miss Hortense reflecting that she wishes she had looked back just one more time to see what was literally no longer there. I wondered what it must have been like for those who didn’t move, the parents of my grandparents seeing a whole generation go because they wanted a better life. But what did it do to that community, that home place? I’ve been in workshops with elders from the Caribbean talking about the Windrush generation, and there was this deep sadness when they spoke of what it was like for them, particularly those who came as children with no idea of why they were leaving their home to go to this place that was often cold and gray, very different from what they had known. Such mixed feelings.

Shea: The novel has two epigraphs, one a quotation from James Baldwin (“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced”) that strikes an ominous note in terms of the mysteries that will unfold. The other is a quote from A Beginner’s Guide to Murder, by Rosalind Stopps. I looked her up and found the comment that her novel “holds so much wisdom yet wears it so lightly,” and I feel that the same could be said of A Murder for Miss Hortense. This is, after all, a novel about immigration from one place to another that may not be so welcoming. There’s one glorious paragraph that begins, “At the heart of everything that surrounded Hortense was a sense of fairness and justice”—and it goes on to talk about what that fairness and justice meant back home in Jamaica in contrast to England, which “for her people, [that] was another kettle of fish entirely.” That kettle is what led them to develop their own banking system—the Pardner network—and the “Looking Into Business” to bypass a law enforcement system that was nonchalant or worse. How did you manage to bring in so much history and social commentary without becoming polemical or heavy-handed—and without losing the flavor of a cozy mystery?

Pennant: I think it comes with Hortense—and my own grandparents. The inspiration for this book is them. There was never this sense of bitterness or licking wounds; everything about them was get up, go, we’re doing this. I don’t think I ever heard my grandmother talk about racism, yet it was there. It wasn’t anything they wore on them like clothes, they shook it off, they experienced it. It’s absolutely there, and we have to navigate it, but it doesn’t define us, it’s not who we are: this is who we are, and this is what we’re going to do.

There was never this sense of bitterness or licking wounds; everything about them was get up, go, we’re doing this.

Talking about the tone of the book—that’s the magic for me. I didn’t want to pretend that these things don’t exist because they do, and, as you say, the Pardner itself existed in this country because they didn’t have access to financial credit or were distrustful of it, so they said we’re going to create our own. That is really the heart of the book: the sense that we’re going to solve these problems, these issues, these crimes, for ourselves because for whatever reason we’re the best people to do that.

But my experience of my grandparents and that generation was not that they wore all these things heavily until it sort of turned them into victims. Far from that. They were very much—I don’t know if stoic or resilient is the right word—it just doesn’t form a part of their character. It is what it is. We move on. I think that’s the tone that the book takes.

Shea: We’ve circled around this question within other questions, but I’d still like to ask it directly: What makes A Murder for Miss Hortense stand out from the mystery pack, as it were?

Pennant: It’s Miss Hortense. She is your typical amateur detective in that she’s an older woman and is ignored for that reason. But when you add her race, the context, what she’s come from, the Windrush community—that makes her different. The Caribbean context and nuances that you get in this book will, if you are not familiar with this world, introduce you to that world. The fact that it’s a Caribbean woman who immigrated to the UK is also really important. So even though it’s fictional, you get to see an imagined sense of what their community is like and what it was like for them coming to a new country in the 1960s—and the wonderful solutions that they come up with to survive, to thrive in those spaces. You get lots of great food, dominoes, music, and humor as well. I really enjoyed being in that world.

Shea: The novel ends by setting the scene for the sequel, which will come out in 2026. Any chance the sequel to the sequel or somewhere down the road, you’ll set the novel in Jamaica? Maybe Hortense could take her nephew Gregory back “home”?

Pennant: There might be. Basically, when I pitched this series to my agent, I had about a hundred different ideas. There’s so much opportunity to go backward, to go forward, so, yes, the third could involve travel.

Shea: In a sassy moment, Hortense says to another of the elders, “We old but we na cold yet,” which for her is quite an understatement. I, for one, can’t wait to meet her again—and again. Many thanks to you.

An Excerpt from A Murder for Miss Hortense

by Mel Pennant

The hat contained, or would contain, forty pounds.

It was more money gathered in ten minutes than many would see in months.

“Now, Miss Banker,” said Errol, directing himself to Miss Hortense, his spirit buoyed again by seeing what was achieved in the hat. “Who going bag first draw? Who going get the whole of this money first?” For that person, it would come like a loan. It would take another seven weeks before they would pay it back with their weekly contributions, and eight before they would get another lump sum themselves. But it was so much more than a loan, as the faces of each of those who had contributed attested as they looked from Miss Hortense to the hat. It was the face of a loved one they could send for and hold close; it was a means to start a little business and to become the person they wrote back home and boasted that they were; it was a little piece of land, a refuge, a house, a church hall, a boxing gym, a community center. It was a future they could plan for, and finally see a path to, and it was a finger up to the Royal National Bank.

No longer were they just a group of individuals striving to make a home for themselves in a foreign land. They were part of something bigger; integral to each other like organs of a body. And Miss Hortense was right at the heart of it.

On that miserable Friday evening in the summer of 1963, Miss Hortense became the banker, also known as the Pardner Lady of Bigglesweigh. She didn’t put herself forward willingly, but she took her responsibilities deadly seriously, and she would not stop being the Pardner Lady, nor taking those responsibilities seriously, until seven years later. That was when she was kicked out of the Pardner in the most humiliating way you could imagine after the thing that no one spoke about happened. Another thirty years would pass, and Constance Brown would have to die, before the remaining members of the original Pardner—well, at least those who were able to walk, that is—were all in the same room again.

Editorial note: Excerpted from A Murder for Miss Hortense, by Mel Pennant. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Mel Pennant.