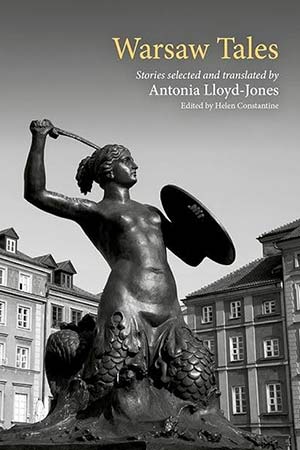

Warsaw Tales

New York. Oxford University Press. 2024. 230 pages.

In 2004 Oxford University Press published Paris Tales, edited and translated by Helen Constantine, a distinguished foreign-language instruction head and now a full-time translator. Constantine followed with French Tales (City Tales) in 2008, Paris Metro Tales in 2011, and Paris Street Tales in 2016. Meanwhile, a “City Series” was born. Edited by Constantine, it focuses on tales from eleven European cities.

Warsaw Tales celebrates the twentieth anniversary of the series. The series purports to educate the “reading traveler” about “important writers who provide them with an intimate knowledge” of a chosen city. Functioning as literary Baedekers, the books provide unique urban portraits through little-known or out-of-the-ordinary events and people and cover a wide range of genres, topics, and time periods, as explained by Antonia Lloyd-Jones in her introduction.

Lloyd-Jones, a distinguished translator from Polish to British English who, in her early career, studied to become a journalist, chose twelve writers with a specialization besides writing: seven are reporters or journalists (Maria Kuncewiczowa, Zofia Petersowa, Hanna Krall, Ludwik Hering, Zbigniew Mentzel, Kzysztof Varga, Bolesław Prus); four are artists (Ludwik Hering, Kazimierz Orłoś, Antoni Libera, Marek Hłasko); Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz was a diplomat; and Olga Tokarczuk’s early specialty was clinical psychology. The tales are presented chronologically—with Lloyd-Jones giving us a measure of her mastery of the Polish language, from “classical” prose to the newest usage and colloquialisms. The tales document a broad territory, from the northern suburb of Marymont to the zoo, and back to the royal route at the center of town.

Such well-rounded and interesting choices are undergirded by Lloyd-Jones’s paradigms of resistance, tragedy, resilience, and extranatural occurrences. Since all authors were engaged in resistance against the Russians, the Germans, and the communist regime, they represent the voice of conscience above political correctness. Iwaszkiewicz, Krall, and Hering recount the many faces of German persecution in World War II, including the Shoah. Petersowa opens the era of postwar tales evoking the macabre resourcefulness developed during the war. Grimness, cynicism, loss of innocence, and poverty show the underside of life under communism; so do Libera’s and Mentzel’s tales about urban planning/mapping, while Olga Tokarczuk describes the hopelessness of psychiatric patients during the last years of communist Poland. The visionary first and last tales by Prus and Varga define the razor-thin line separating reality from surreality in the lives of Varsovians.

Most importantly for Lloyd-Jones, these stories honor the spirit of the enduring myths and legends of the “phoenix” city.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin