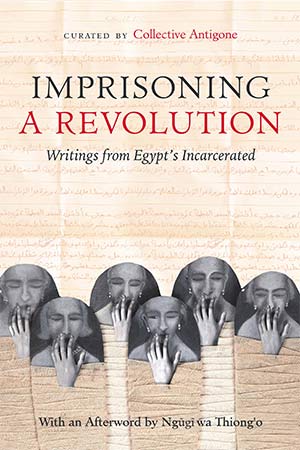

Imprisoning a Revolution: Writings from Egypt’s Incarcerated

Curated by Collective Antigone. Oakland. University of California Press. 2025. 336 pages.

“Writing is the highest form of resistance,” articulates acclaimed Egyptian journalist and writer Ahmed Naji in his foreword to Imprisoning a Revolution: Writings from Egypt’s Incarcerated. This powerful assertion, the link between writing and resistance, reverberates throughout the volume. Within these pages, poems jotted down on scraps of paper and letters smuggled out at tremendous personal risk become potent acts of rebellion. These harrowing firsthand accounts, from journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens—some seasoned writers, others fashioned into writers by the crucible of imprisonment—are not just whispers but defiant breaths against a suffocating silence.

These writings, visceral and immediate, testify to the enduring human need to bear witness and speak truth to power. They expose the manipulation of the legal system, revealing how vague charges grant authorities unchecked power to detain prisoners of conscience. More than just outlining legal injustices, these testimonies offer a gut-wrenching understanding of what it means to be imprisoned. They delve into the deliberate attempts to confine the body, to break the spirit, to erase identities, to crush dignity. Political prisoners are systematically humiliated: stripped of their belongings, their names, and reduced to dehumanizing numbers.

However, the voices within this collection cut through the noise, compelling us to confront the human cost of this systematic brutality. They demand that we move beyond dry statistics and legal jargon to grapple with the lived experiences of those behind bars. Surprisingly, the human spirit flickers even in the darkest jails. While each story is uniquely harrowing, common threads of resilience emerge.

Some prisoners retreat into elaborate dreamscapes, forging mental escapes from the grim reality. Ayman Moussa’s poignant testimony, for instance, captures the psychological toll of prolonged confinement, where reading becomes a lifeline, each book a temporary portal out of his dungeon. Likewise, activist and filmmaker Sanaa Seif finds solace in the promise of a good book. “I shall fall asleep looking forward to a tomorrow in which I’ll read my book,” she writes. These accounts highlight how fundamental human needs for connection and purpose are weaponized behind prison walls. A particularly disturbing thread that runs throughout the book is the regime’s targeting of the most vulnerable—those already marginalized for challenging societal norms and demanding their rights. Transgender activist Malak al-Kashif was imprisoned for her outspoken views against gender-based discrimination and violence. Women’s testimonies repeatedly emphasize the “double marginalization” they face as both women and political prisoners.

“Prison is a microcosm of society,” observes human rights lawyer Mahienour El-Massry, her words a stark indictment of the panopticised society. The afterword, featuring the towering Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, provides a powerful parallel. His experience of incarceration, though born of a different context, resonates deeply with the stories of Egyptian prisoners, underlining the universality of the struggle against oppression and the indomitable spirit that allows survival. Imprisoning a Revolution challenges us to confront the brutal reality of prisons, reminding us that they are not merely places of confinement but active instruments of torture. Silence is complicity, and even the smallest acts of solidarity can make a difference. (Editorial note: Rob Roensch’s interview with Ahmed Naji appeared in the November 2023 issue of WLT.)

Ibrahim Fawzy

Boston University