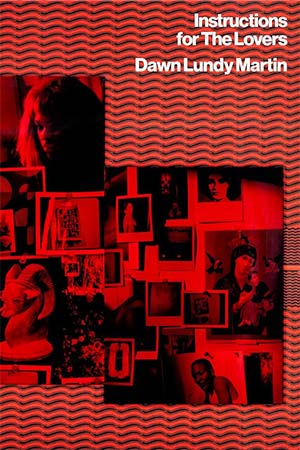

Instructions for The Lovers by Dawn Lundy Martin

New York. Nightboat Books. 2024. 92 pages.

Dawn Lundy Martin is the author of four previous books of poetry as well as three limited-edition chapbooks. She has also published essays and crafted a stellar reputation as an academic innovator. She was the first person to hold the Toi Derricotte Endowed Chair in English at the University of Pittsburgh, where she co-founded and directed the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics. Martin has vocally acknowledged the influence of her mentor and her teacher—Toi Derricotte and Marilyn Nelson. Several of the poems included in this volume were first published in a chapbook collaboration with Derricotte.

The poet has blended a challenging academic career with an output of outstanding poetry, as exemplified in her new collection: Instructions for The Lovers. Her poetic field is dense with thought, image, and sound in poems about aging, attachments, and the fragility of a poet’s life. In these verses, she reflects on her relationship with her mother, her own queerness as a lesbian experimenting with sex, and on the racist conditions encountered and overcome within the American academic system.

Martin has won numerous battles. She has received the Academy of American Arts and Sciences May Sarton Prize in Poetry. Her poems have been described as “dense and deep . . . necessary, and hot on the eye.” The tension between language as a tractable, yielding construct and the physical expressions of language in writing and speech form the center of these poems—logical yet fraught with emotion. The opening lines of the book are spread over several pages as words forming one or two short verses and set in the center of blank pages with caesuras interrupting each line. These fragmented utterances seem to represent the poet’s attempt at finding the right words while mimicking a childlike speech. Yet, later in the collection, her words take on a sudden continuity:

The entanglement of loverness meant that when the world disappeared, we could not feel our subjugation. Cradled by the beloved. Enveloped, however temporarily, in the confines of bloom, the consumption of the ego. We swagger forth into our gendered selves alongside American rivers . . .

In an ars poetica, a poem titled “About Art, D+D,” Martin explores her personal aesthetic as it unifies all artistic production. Art stands alone. Art is an entity unto itself:

We must make language of all forms

of art together.

What art produces is a different

language – untranslatable.

But then why want to ask questions

when looking at art?

Language happens to be how we

know ourselves to exist.

Another way toward this is that art

casts a spell. Not on no one.

And material or substance is

produced inside of the interaction.

For Martin, art possesses the quality of a necessary being, as necessary as language itself. Art is relationships “made possible by that interaction between persons and art.”

Martin’s poetry is philosophical. Her poems have been compared to the lyrics of the French symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who lived and wrote in the latter half of the nineteenth century. His poetry also featured difficult, often torturous syntax, ambiguity of expression, and obscure imagery. Among his themes, a theme also taken up by Martin, is the poet’s longing to turn his back on the harsh world of reality and to seek refuge in the world of ideas. Martin seeks to write something other than mere descriptive lyrics dealing with objects in the real world. She attempts, as does Mallarmé, to give poetic form to an immaterial world.

Language, in these poems, becomes the poet’s medium through which she explores desire, love, grief, fear, and the tenuous vulnerability of the human condition.

Beth Brown Preston

West Chester, Pennsylvania